Nafis Azad/Collegian

Nafis Azad/CollegianIt’s 12:55 a.m. on a Saturday night – last call in the college bars in downtown Amherst. Hundreds of inebriated students crowd the sidewalks, screaming, laughing and gobbling slices of pizza. Dressed in a faded black sweatshirt and a sparkly blue cape, Bennie Johnson, known to most of the college town as Motown Bennie, leans against a tree outside Judie’s Restaurant. He fidgets, tossing his instrument – a white construction bucket – in his hands, waiting until the bars empty out and the sidewalks are filled to maximum capacity.

“I have to stay out of the bars,” he said. “When I try to go in and get a drink of tequila or a margarita, 15 or 20 drinks will appear because the people all want to buy me drinks.”

A well-known street musician in Amherst, Motown Bennie has been performing Motown, jazz, and classic rock songs on the town’s sidewalks for over three years. Armed only with his battered bucket and a kazoo for instruments, he says he sings because it makes people smile.

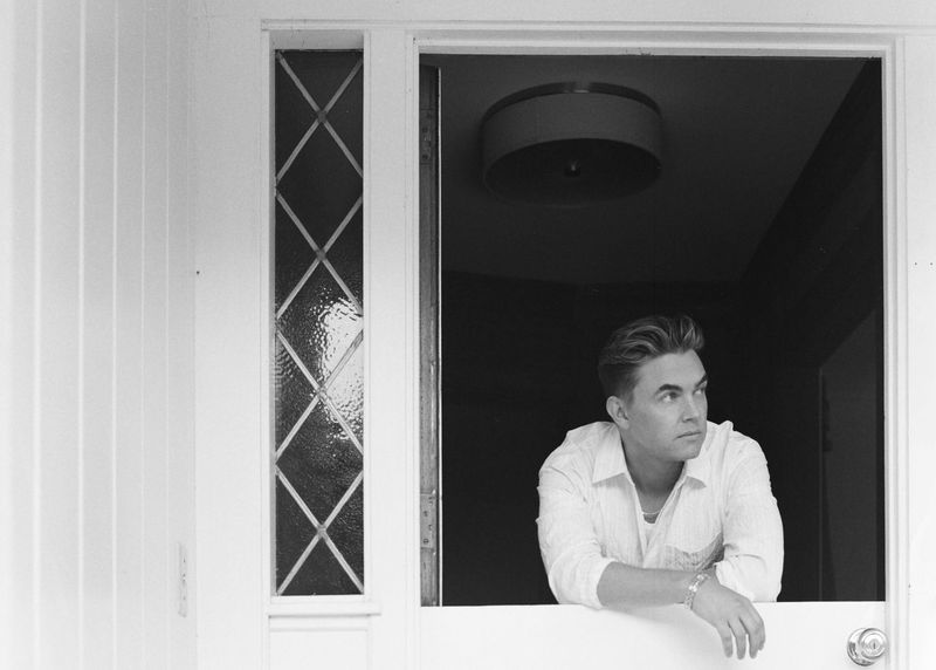

The sight of Motown Bennie renders nothing but stares. The 6-foot, 190-pound musician’s performance costume involves a scrap of shimmery metallic cloth tied around his shoulders into a cape. His neck is often adorned with strings of fluorescent Mardi Gras beads and a bright orange kazoo. At first glance, the graying 59-year-old could be mistaken for an escapee from a local mental institution.

However, underneath his costume, Bennie looks like any other blue-collar worker, dressed in a collared sweatshirt, Dickies and a pair of work boots.

“Motown! Motown Man! I’m in love with this chick I just met,” screams a student from the stoop of a nearby bar. “Make her love me back!”

With a smile and a wink, Bennie begins beating on his battered white construction bucket, singing an old rendition of The Temptations.

“Sugar pie, honey bunch You know that I love you I can’t help myself I love you and nobody else…”

Instantly captivated, the sidewalk crowd throngs to form a circle around Johnson. The cheers and clapping are deafening as shouts of “go Motown Man” echo across the street. Soon, half of the street is dancing.

Despite his age, Bennie is able to stay out in all kinds of weather, often performing until 2 a.m.

Several officers from the Amherst Police Department look on from across the street, more amused than concerned.

“They let me play because I work as a type of crowd control,” said Johnson. “My music makes people feel good, so they are less apt to fight and get out of control after the bars. It makes my job easier and the cops’ job easier.”

The first time I met Motown Bennie was four years ago, while walking in downtown Northampton. I had just finished one of many fights with my then-boyfriend, and I sullenly held his hand, trying to look anywhere but his face.

“The blonde girl is mad at her boyfriend!” sang a voice from the street corner.

I turned to gawk at the tall black man in a sparkly red cape, singing and banging on a bucket.

“He won’t be with us very long!”

Like anyone who has just heard Motown Bennie for the first time, all I could do was stop and laugh. While he is a cultural icon in the Five College Area, very few people know much about Motown Bennie other than his street performances. Like most, I also knew nothing about him, until I spent a day in the life of Motown Bennie.

A taste of the South

The smell of frying chicken and cigarette smoke saturates the dim, one-bedroom apartment in Colonial Village, Amherst. Under a single ceiling light sits Johnson’s friend and housemate, Patricia Rose, lazily puffing at a cigarette. Rose moved in with Johnson three years ago after begging him to take her out of the nursing home where she lived.

Unable to work for years because of mental illness and diabetes, Rose spends much of the day in a drowsy state due to the side effects of the 32 prescription pills she is required to take. Instead, she functions as Bennie’s private secretary, organizing the overwhelming number of requests for Bennie’s appearance at private parties.

It’s an unusually warm day in late March, but the apartment is chilly, and Bennie wears a knit hat and a faded sweatshirt as he peeks his head around the kitchen corner.

“I’m making fried chicken for you!” he exclaims. “You ain’t never had southern fried chicken until you’ve had mine.”

The three of us crowd around the tiny table on bar stools. Rose puffs silently at another cigarette, staring sleepily at the wall. I hungrily bite into a chicken leg, wiping my greasy fingers on a paper towel, sipping on a glass orange soda. Johnson watches eagerly.

“What do ya think? Good? Do you want more? Are you still hungry?”

Bennie will cook food for anyone who wants it. When he’s not performing, he spends his time buying groceries, preparing meals, and delivering them to needy families nearby.

Today, Bennie has cooked enough for two additional families. He dishes the chicken out into containers and plastic bags to deliver to other friends in the complex. Johnson spends over $100 a week on food, and much of it he gives away. It’s only 11 a.m. and already there are six hungry people from North Amherst who are scheduled to drop by his apartment for a hot meal.

“I can’t just cook food for two people,” said Bennie, looking at Rose. “I can’t turn nobody away. Even if it’s my last box of cereal, I can’t say no. I’m always thinking about somebody else.”

Although Bennie is supported almost solely by the money he earns as a musician, he won’t talk directly about how much he makes. A good night might bring $125. A bad night can bring nothing more than a five-dollar bill.

Unemployed since he suffered a back injury several years ago, Johnson collects disability from the state, but refuses to go on welfare.

“I never wanted to take social security because it takes away your dignity,” he said. “I totally support myself. I think I’m creative enough with that bucket to make a living with it. I ain’t embarrassed if it makes people happy. My gift is making people laugh.”

While Rose’s Social Security checks help pay some of the bills, money is always tight for Bennie. An unused television sits in the living room, serving as a reminder of the things he can’t have.

“We’ve had to cut down to 10 hours of regular TV a month,” he said, shaking his head. “Rose sleeps a lot more now.”

Bennie hasn’t slept in his own bed in almost three years. After giving up his bedroom to Rose, he has permanently moved onto the main living room couch. The second couch is often taken by someone who needs a place to sleep.

There is a knock on the apartment door. Two women dressed in sweatshirts and jeans come in, and each hug Bennie. They sit on the apartment couch side by side, while Rose takes a recliner to talk to them. One of the women is crying: her son’s godfather has died, and she’s seeking solace. The other is hungry, and in need of a place to rest her bad foot for an hour.

Bennie says although he has little himself, he still offers what he has to others, even if it’s only a place to sit down.

“I do what I do because there was a time when I had nothing,” he says.

Listen to the music

Born in 1947 in New Orleans and raised in Baton Rouge, Bennie was one of five brothers and a twin to his only sister. His father worked seven days a week as a digger in the local oil fields. When the acids from the mine tanks stung his father’s eyes to the point of temporary blindness, Johnson would follow his father to work and hide in the woods. Behind the boss’s back, Bennie would switch places with his father and dig while his father took a much-needed rest.

“My daddy worked so hard,” said Bennie, wiping the tears streaming down his cheeks. “They worked him to death. I tried to work for him, but he was always so tired.”

Although the family was

poor, Bennie said his mother, Josephine Cooper, taught her children to appreciate the sounds of jazz and blues. All the children learned to play the piano, drum, and guitar. The jukebox was one of the family’s most prized possessions. By age 11, Bennie was an advanced washboard player and singer.

On summer nights, Cooper would load the children into the family’s old Desoto and take them to Alligator Buoy – a shack of a music bar in the middle of the Louisiana swamps, where alligators sat in the parking lots, and the greatest of the great musicians played.

It was here that Johnson first saw the performances of great legends, like Ray Charles, B.B. King, and Fats Domino.

“It stayed with me,” he said. “And I came to love music more than anything else.”

Despite his gift for music, Bennie was unable to concentrate much in school. “I couldn’t stand the racial tension,” he said.

Although he was one of the school’s top athletes in track and baseball, Bennie dropped out his senior year after two white boys hit him over the head for accidentally drinking out of a white-only water fountain after practice.

“I was so thirsty, I forgot to read the sign,” he said.

Determined to get out of the south, Bennie took a job as a movie theater usher. The job quickly ended after his boss caught him talking to a white girl. After being jumped by the manager and a coworker, Bennie said he was dragged to the back office, where the cops were already waiting. After several shift kicks in the ribs and a crack across the face, the police left him bleeding on the theater floor.

“They beat me up, but they didn’t arrest me,” said Bennie. “The manager needed me to work the rest of my shift.”

Bennie’s second job brought him to a steak house where he worked as a cook.

“All the white employees were allowed to eat the steak, but the black ones weren’t,” he said. After one particularly grueling night, Bennie broke down and ate two steaks during an evening shift. In response, the manager refused to pay Bennie for a month.

“After that, I couldn’t wait any longer,” said Bennie. “I had to leave Louisiana.”

Bennie said he waited until the restaurant closed, broke open the cash register, and emptied the $250 into his pocket. He fled that night by bus to New York.

He later met his wife of 37 years, Margarita Johnson, and raised a family in the Florence Heights apartment complex in Northampton. Bennie’s three children, Petey Johnson, 32; Joseph Johnson, 28; and daughter Margarita Johnson, 30, all live locally.

Family values

Despite his busy schedule, Bennie says his top priority is visiting his wife. Margarita Johnson, 57, resides in the Calvin Coolidge Nursing Home ‘ Rehabilitation Center in Northampton.

After battling multiple sclerosis for 22 years, Johnson was admitted to the nursing home three years ago when her health care became impossible to continue at home.

Bennie says he spends his visits bathing his wife and cooking for her.

“For everything I do, I make her pay me in kisses,” says Johnson. “She laughs a lot, just like I do. She tells me everyone in the nursing home is jealous.”

There is another knock at the apartment door, and a tall bearded man jogs in, holding his jaw. Bennie greets the man with a smile and a hug. But the tall man is not smiling back.

“Bennie, look at my tooth,” he said, pointing to a large swelling on his lower jaw. A bad tooth is causing a serious infection.

“It’s freaking me out. I dunno what to do.”

“We got to cut this short,” Johnson says to me, eyeing the infected area. “We got to get him to a dentist.”

As he turns to run out the door, Bennie tucks his blue cape and white bucket under his arm. He’ll play his bucket and sing on the way to the dentist, hoping to soothe his friend’s nerves.

“See. There’s always people who are gonna need music and a smile,” he shouts back to me.