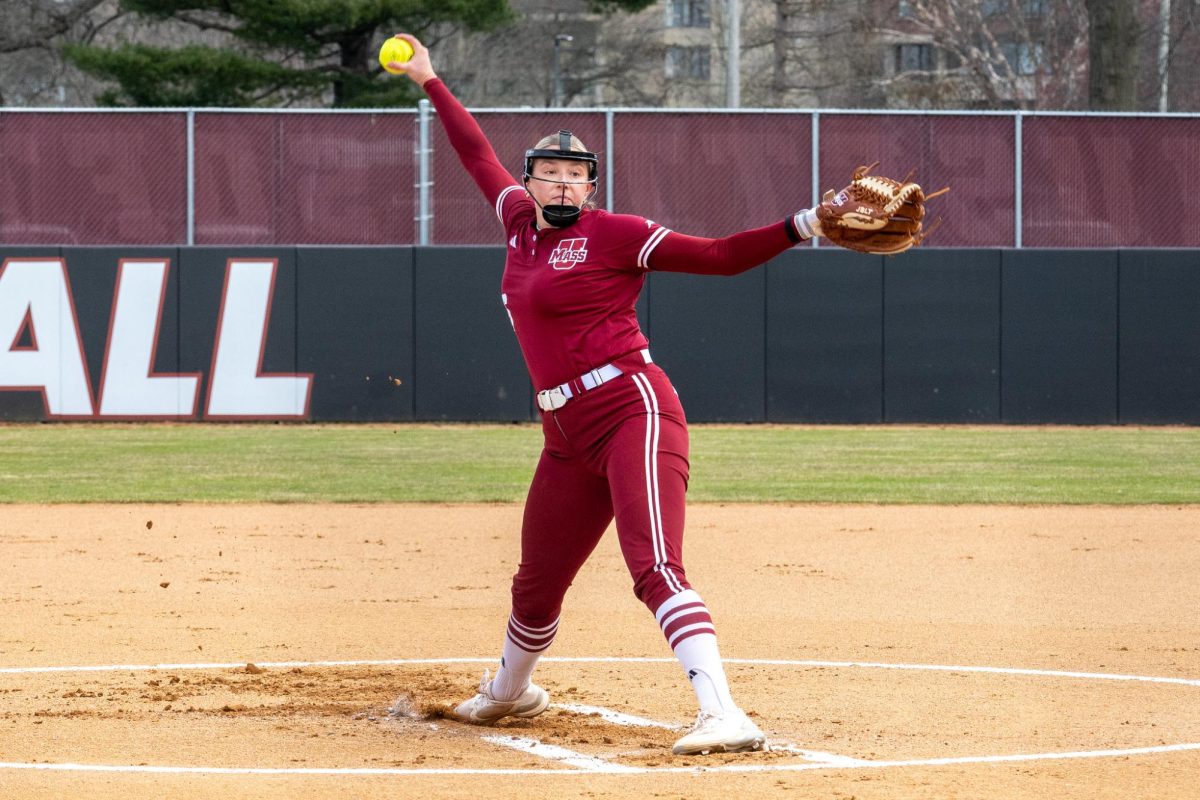

Andrea Murray/Collegian

Andrea Murray/CollegianIt’s a late afternoon on Tuesday at the Bluewall Cafe and Steven Brewer, the founding father of the Amherst Esperanto Club, is telling a story about a man he knows through Esperanto, Dave Coffin from Andover, Mass.

Coffin went to an Esperanto conference in Russia where he met a Russian woman and fell in love. They moved back to the U.S., and they have two kids. She speaks Russian to the kids. They all speak Esperanto together as the official house language because that is the only language that Coffin and his wife share in common. The children are learning their English from TV and school.

Esperanto seems to be the new language of love. The group told numerous love stories in which two people who only had Esperanto in common fell in love and never learned each other’s native languages.

Dr. L. L. Zamenhof invented Esperanto and published the first book in 1887 under the pseudonym “Dr. Esperanto.” The word Esperanto means “one who hopes.” The language was created to allow communication between people of different lands and cultures. Interest in the language peaked in the 1970s.

Sometimes criticized for being sexist and sounding too artificial, it currently has not fulfilled its original intent of becoming a universal language. Some have even complained that Esperanto could take away from native languages, but that is not the intent.

“It is important to note that Esperanto is not meant to replace native languages, but it is meant to be every person’s first second language,” says Julie Winberg, an active member of the club.

Today, there are about 2 million Esperanto speakers, about 1,000 of whom are native speakers. At the University of Massachusetts, a loyal group of followers still practice the language. They meet each week to discuss readings and practice speaking in Esperanto, the most widely used international auxiliary language.

UMass Professor of Biology and Amherst resident Steven Brewer founded the Esperanto group about five years ago. He met other Esperanto speakers, like Sali Lawton of Westhampton, on the Internet. His mother, Lucy Brewer, is another attendee.

The sound is hard to describe, but it’s closest to a mix of German and Spanish. Winberg says that people often think that it sounds like whatever languages they know. She once thought that it sounded like Italian but her Italian friends firmly disagreed.

Everyone in the group seems to agree that learning Esperanto opens doors, especially in the travel world.

Esperanto is a phonetic language that uses no silent letters. Esperanto.net says that about 75 percent of the language comes from Latin and Romance languages, about 20 percent from Germanic languages and the rest comes from Slavic languages and Greek. Word order is not important in Esperanto, and there are few grammar rules.

Brewer and Winberg shared a few simple grammar rules: all words that end in “o” are nouns; diphthongs, vowel sequences pronounced as a single new sound, make words plural; “la” means “the,” no matter what. There is no difference between feminine, masculine and plural case.

Winberg lectures on topics like women travelers at the World Conferences of Esperanto. She was once the President of the Women’s Commission of the World Esperanto Association. She has traveled all through Eastern Europe using only Esperanto because the only other language she knows is English. Winberg says that wherever she went, she found some people who spoke Esperanto.

Lawton, a fourth grade teacher for 11 years, is another long-time member. She learned the language in 1985, and soon began volunteering to teach Esperanto to her students during summer breaks.

“After the kids got out of fourth grade they would come up to me and say ‘I still have my Esperanto papers!'” says Lawton.

Esperanto has its own original literature, including books and magazines as well as movies. Monato is a popular all-Esperanto magazine. There are over 25,000 Esperanto books, originals and translations, in existence. Zamenhof even translated the “Old Testament” into the language.

“Incubus,” made in 1965 starring William Shatner, used Esperanto not because of its popularity, but for the exotic sound of it. The film was the first American motion picture completely in Esperanto.

Esperanto.net says that it is easier to learn than national languages. The Amherst Esperanto club recommends using Lernu.net to learn Esperanto quickly and free of charge.

“I have chatted with people online in Esperanto and at the end of the conversation asked them, ‘So how long have you been speaking Esperanto?’ and they say, ‘Oh, last week,'” says Brewer.

Brewer is the director of the Biology Research Center at the University of Massachusetts and is fluent in English, Spanish and Esperanto. He says that he became fluent in Esperanto in just six months but it took him years of book study to become fluent in Spanish. He learned Esperanto as a graduate student but regrets not studying it earlier on.

“I wish that I had learned it as an undergraduate because I could have made connections and traveled more,” says Brewer.

Brewer has taken advantage of the camaraderie among his fellow Esperantists. Other Esperantists are often very willing to let other speakers stay in their homes because they have the language in common. The Amherst Esperanto Club is just a small division of the Esperanto family.

Andrea Murray can be reached at [email protected].