Near the beginning of “The End of the Tour,” author David Foster Wallace (Jason Segel) allows Rolling Stone reporter David Lipsky (Jesse Eisenberg) to sit in on the creative writing class he teaches at Illinois State University. As they walk down a hallway toward his classroom, Wallace tells Lipsky, “Don’t expect any fireworks.” I’d say the same thing about this movie. “The End of the Tour” is a moving, intimate film that examines anxieties about achievement and failure.

The ending tour in question is Wallace’s promotional circuit for “Infinite Jest,” his sprawling novel with an equally sprawling readership. The book captivates Lipsky – who has a meager literary following himself – so he convinces his editor to let him write a profile on Wallace. The film focuses on the five days these two Davids spent together.

At times “The End of the Tour” feels meandrous – its plot consists almost entirely of the ongoing conversation between Lipsky and Wallace – and I suppose that’s the point. Director James Ponsoldt and screenwriter David Margulies wring great emotional and thematic heft out of this central interaction. I was drawn to these creative people – to their honest thoughts about the emptiness of public attention. In one scene, Lipsky questions Wallace’s dissatisfaction with his sudden success. Wallace responds, “This is nice; this is not real.”

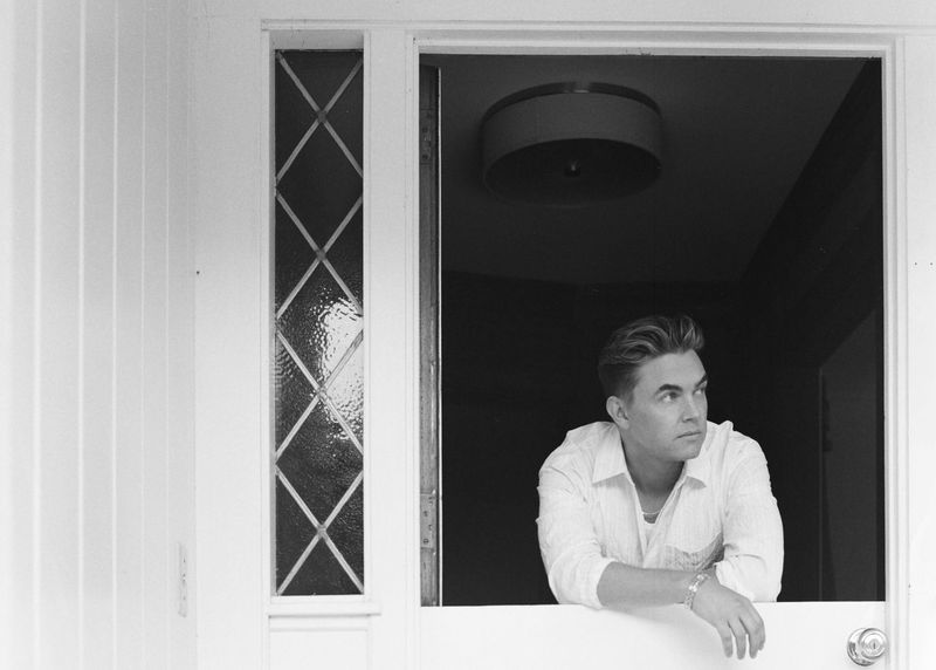

I haven’t read much of David Foster Wallace’s work, nor am I familiar with his life or public persona. Watching Segel’s portrayal felt like an introduction to a man I’ll never know. Wallace reveals a deep self-consciousness as he speaks with Lipsky. His sudden fame makes him uncomfortable, and he often shrinks into himself when pressed to answer more incisive questions. Wallace says he “treasures [his] regular guy-ness,” and Segel masterfully embodies the reserved, unassuming manner of a man struggling to stay out of public scrutiny. He speaks and moves carefully, physically burdened by the weight of demons he’s hesitant to discuss.

Eisenberg is less compelling as Lipsky. His stilted, nervous inflections and chilly demeanor are starting to feel like a shtick. I didn’t get a sense of who Lipsky was while watching him. His screen time here could have actually been recycled footage from “The Social Network” or “Now You See Me” and I wouldn’t have noticed. That’s not to say that his acting is bad – it’s just almost exactly the same as everything he’s done before.

Ponsoldt effectively builds tension around two men who don’t let their guard down. Even though Lipsky genuinely admires Wallace, he can’t shake an inherent jealousy. In a voiceover, Lipsky says, “He wants something better than he has; I want precisely what he has already.” When the reporter stays overnight in Wallace’s guest bedroom – filled with copies of the author’s books –editor Darrin Navarro smartly cuts between the imposing stacks and Lipsky’s envious eyes.

Lipsky’s Rolling Stone boss pushes him to get a juicy story out of Wallace, and it’s compelling to watch the ensuing conflict unfold. The reporter tries to keep his interactions with the author honest, but his assignment forces him into uncomfortable territory. Some of the film’s best scenes are arguments between interviewer and interviewee – Segel’s Wallace is magnetic as he explains the haunting truth of his personal struggles and rebukes Lipsky for trying to capitalize on cold, vampiric journalism.

The true story Lipsky writes about Wallace proves far more affecting and engaging than the salacious exposé that he was urged to write. Wallace admits that no amount of gratification from fans or critics makes him feel any less isolated when he returns to a blank page in an empty room. That unshakeable feeling of loneliness resonated with me. While many acts of creation are communal efforts, writing can often be a dishearteningly solitary craft.

When I sat down to watch “The End of the Tour,” I realized that all of my pens had dried up. Frantic, I walked out to the lobby, explained that I was a film critic and asked to borrow a pen from the clerk. Then, around the middle of the film, Wallace disparages the practice of saying “I’m a writer” ad nauseam as smutty and self-indulgent. Segel spoke with such conviction in that moment that I questioned if my earlier self-identification was appropriate.

Wallace mentions in another scene that he never writes without purpose. That’s probably the best way to justify my motivation for calling myself a critic, asking for that pen and writing notes for this review. I had a purpose – to call attention to this film, so that a potential reader who decides to trust my opinion might go see it. “The End of the Tour” made me feel, it made me think, it comforted and challenged me like an old friend. I think that’s well worth sharing.

Nathan Frontiero can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @NathanFrontiero.