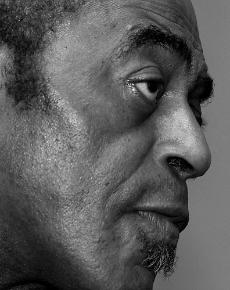

Archieshepp.com

Archieshepp.comIn his autobiography, “Live at the Village Vanguard,” Vanguard founder Max Gordon describes Professor Archie Shepp as a “professor of jazz at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst” before there is any mention of saxophones or club dates. “It’s an innate quality I’ve always had,” said Archie Shepp, 69, during an interview with the Daily Collegian in December. “I’ve always enjoyed sharing information with other people. Teaching at the university level was really exciting to me.” Shepp taught at UMass for 30 years beginning in 1971. He taught two classes: “Revolutionary Concepts in African-American Music” and “Black Musician in the Theater.” “Revolutionary Concepts” followed the history of African-American instrumental music from its origins in Africa to its current incarnations today. “So we see John Coltrane as a product of an entire experience that cannot be extrapolated from [Louis] Armstrong,” said Shepp. “There is continuity in Black Music which begins in Africa and is still important today when we hear a performer like Branford [Marsalis]. Or Aretha Franklin. All related by a set of circumstances.” Differently, “Black Musician in the Theater” was performance-oriented, with an emphasis on improvisation, the blues and songbooks of Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk, including Parker’s “Now’s the Time,” and Monk’s “Straight, No Chaser.” “The idea was to give these students a chance to do what they would do on the bandstand,” said Shepp. Ironically, Shepp himself did not frequent the bandstand during his time at UMass. “The first 20 years I was here, I made up my mind that music performance would have to take a backseat to teaching,” said Shepp. “Most of my performances took place during the summers.” When Shepp did miss class, alto saxophonist Marion Brown, who appears on Coltrane’s “Ascension” alongside Shepp, often took his place. But no one took Shepp’s place in the studio. Between 1971 and 2001, more than 40 albums were issued under Shepp’s name, for labels like Black Saint, Soul Note, Enja and Impulse!, who signed Shepp on Coltrane’s recommendation. “After Coltrane, there was really nothing that happened,” said Shepp. “Maybe the avant-garde.” The avant-garde, or “free jazz,” has a substantial following in the Pioneer Valley, as evidenced by the response to Glenn Siegel’s “Magic Triangle” and “Solos ‘ Duos” concerts, and the ongoing Eremite music series, often staged at the Unitarian Meetinghouse in Amherst. But this worries Shepp, a pioneer of the music. “The audience becomes more and more white and middle-class,” said Shepp. “Go into a black community, in Chicago, or I was recently in Florida, and people listen less and less to the instruments. Hip-hop, rap, break-dance [music] have four bars, or two bars of a saxophone solo or trumpet solo. That’s what has become of the music you call jazz. It’s essentially dance music. Jazz is a dead music like Latin is a dead language.” According to Shepp, this phenomenon is due in large part to the fact that many African-American artists no longer live in African-American communities, something that once kept the music fresh, and vital. “Unfortunately, things changed quite a bit after the 1960s,” said Shepp. “Before, Dexter [Gordon] and Dizzy [Gillespie] lived right in Harlem. There was Minton’s, and The Apollo. All these places have moved downtown, places where working-class people are not apt to go.” Also worrisome to Shepp is the perpetuation of the term “jazz,” a “brand name” that, for many, refers to anything but what drummer Albert “Tootie” Heath calls “American Classical Music,” or what Shepp calls “African-American Instrumental Music.” “We created this music,” said Shepp. “The irony is that everyone is so timid about calling it African-American music.” Shepp is quick to point out, however, that someone like Stan Getz should not be disallowed to play the music because he is white and Jewish. But Shepp believes in giving credit where credit is due. “If I have heard a Greek chorus singing “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” does that mean African-American spirituals come from Greece?” asked Shepp. “It doesn’t change the identity of the experience.” Such an experience informed the work of a number of African-American artists-turned-UMass-professors, like Yusef Lateef. “He was a hero to me when I was 17-years-old,” said Shepp of Lateef. “He did a lot to enrich the palette of so-called jazz music. He showed that jazz has as much scholarly and intellectual aspects as any other music.” Drummer Max Roach taught full-time from 1973 to 1978. “I first began listening to Max Roach as a teenager,” said Shepp. “I was impressed by his music and intellectual career. He always tried to demonstrate that Black Music was a music of liberation and struggle. He was very important for me for that.” One-time Coltrane bassist and former Jazz Messenger Reggie Workman taught bass at UMass from 1972 to 1974. “Reggie and I grew up together, and it was edifying to work with him again,” said Shepp. Workman and Shepp co-led an improv workshop while Workman was at the university, but the bassist did not receive tenure, and left in 1974. Shepp recommended that Ron Carter or Richard Davis be hired in lieu of Workman, but neither musician was taken on. “Not only did we lose Reggie,” said Shepp, “but we never got anyone to replace him.” Workman’s termination aside, Shepp recalls the 60s and early 70s as an exciting time. “When I began teaching college, it was the end of the civil rights movement,” said Shepp. “Socio-cultural issues were very much in the forefront and very much related to artistic events. Coltrane and Cecil Taylor were at the point where they began to drop harmonic elements and began to explore more rhythmic and pentatonic [approaches] and depart from the diatonic music that came before.” African-American instrumental artists also made political statements with their song and album titles at the time, according to Shepp. Charles Mingus’ “Fables of Faubus” referred to the Arkansas governor who famously blocked nine African-American students from entering an all-white high school in 1957. Coltrane’s “Alabama” was inspired by a Birmingham church bombing in 1963 that resulted in the deaths of four young African-American girls (the same church bombing inspired Spike Lee’s 4 Little Girls documentary). Shepp also cited Sonny Rollins’ “Freedom Suite” and Roach’s “We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite.” “Music that had not been associated with political events took us back to the days of protest songs and slave songs black people used to declaim oppression,” said Shepp. Music and the arts, however, have purposes beyond the political, according to Shepp. “Art makes us less bellicose,” said Shepp. “The nature of art is to encourage friendship and love