The School of Public Health and Health Sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst held a panel event in which “Women Behind Bars: Public Health and Criminal Justice Reform” on September 27.

The event was held at the Campus Center in room 904 at 4 p.m. and featured keynote speaker Andrea James, the founder and executive director of Families for Justice as Healing, Kenzie Johnson, a co-organizer of the anti-shackling advocacy group Prison Birth Project, Dr. Melody Slashinski, an assistant professor of community health education at UMass, and Kim Gilhuly, a leader in the Human Impact Partners’ “Health Instead of Punishment” program.

The event began with James talking about growing up in Roxbury, Massachusetts, with a family of doctors and lawyers who she described as “educated hippies,” since both her parents marched with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. during the 1960s.

James graduated from UMass Boston and then went to law school at Northeastern University, becoming a fully licensed lawyer.

However, later in her life she was sent to federal prison for two years, as she was found guilty for wire fraud after losing money in a real-estate transaction and attempted to cover it up.

When she was sent to prison, James was 45 years old with a five-month-old baby boy who she was still breastfeeding. She was also a mother to several other children.

The prison she was sent to had a population of 2,000, 95 percent of whom were African Americans or Hispanic Americans sentenced for drug crimes. James described this blatant inequality as “outrageous and disgusting.”

James said her first experience in prison was having a correctional officer (CO) perform a strip search on her, an experience which she called “degrading and humiliating.”

She did six to seven months of prison labor, where she and other women would clean a Greyhound prison bus all while having chains shackled to their limbs and waists.

She then spoke on the inhumane treatment of women being transported to prison across from the country. According to James, these women must take planes where their limbs are shackled with chains until the end of the plane ride. While they are there, these women cannot make phone calls, use the restroom or use feminine hygiene products.

When the plane stops at a center, the women are forced to shower in front of male COs, while still in shackles. Afterwards, they are given paper suits and put back on the airplane, forced to walk by male COs. Some women, James said, are still covered in menstrual blood and vomit from their first time on a plane.

James herself was a tutor at the prison. She was given her own class to help pass the general education degree exam. However, the class had slowly turned into an organizing space for the women. Since organizing was highly forbidden in the prison, the COs had tried to disrupt the class by shutting out all mail and books James had ordered. To her advantage, she had her father send copies of books by chapter for her to distribute to the class.

James then spoke about the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), which she described as the architects of hard-on-crime policy. James recalled the day the women sat around listening to news reports, talking about ALEC and ending mass incarceration. However, she had felt like despite all this talk, still, nobody was talking about women.

According to James, 85 percent of incarcerated women were the primary caretakers of their children, so incarcerating mothers leaves their daughters to become vulnerable to human trafficking.

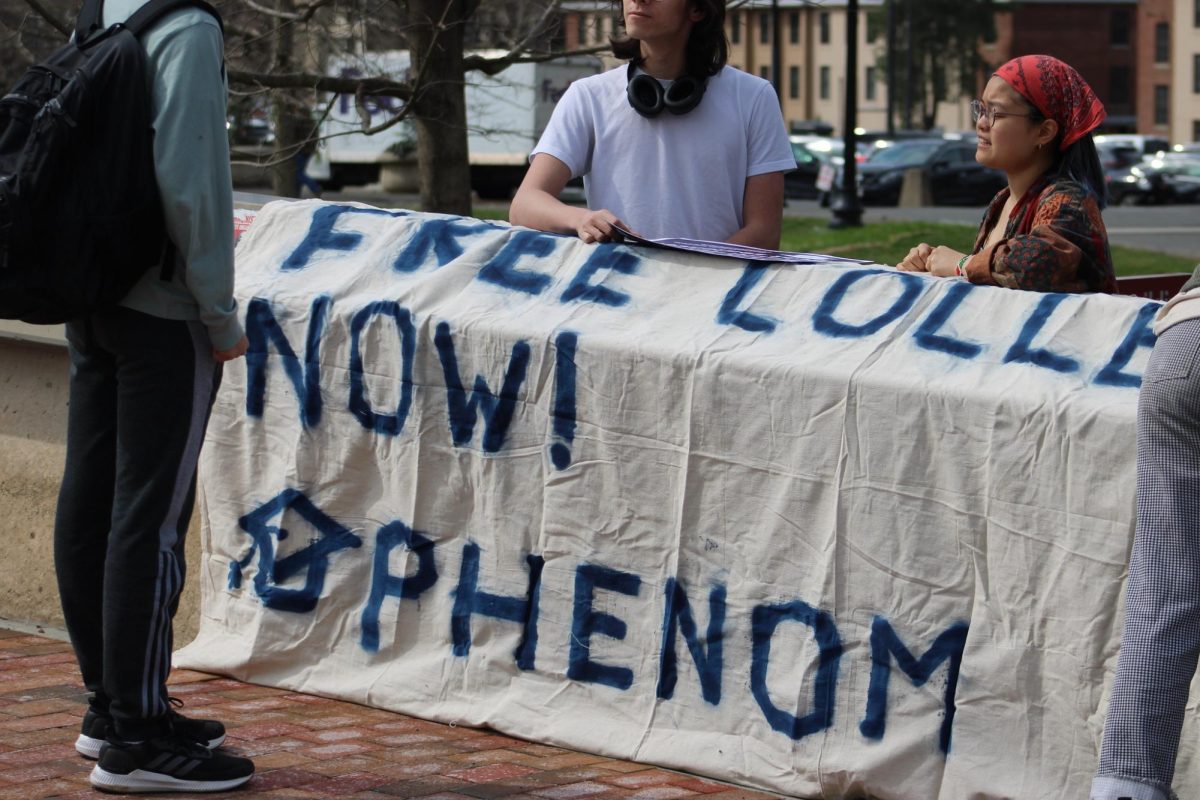

James also began to work on ending chain shackling of women at her prison, which finally ended roughly around the same time she got out. However, chain shackling is still practiced in prisons today.

James a is a self-described prison abolitionist. She is working on passing Massachusetts Senate Bill S770 which would allow for an expansion of set community-based sentences for parents.

The next speaker was Kenzie Johnson, who was incarcerated in prison while four months pregnant.

When it was time for her to go into labor, she recalled how the COs were hesitant to take her to hospital. When they eventually decided to send her, Johnson was put into the back of a police cruiser without seatbelts or anything to grasp onto, while being shackled.

When Johnson arrived at the hospital, the hospital staff had to beg the COs to remove the shackles. The COs eventually complied however. After giving birth, Johnson was immediately shackled again, and her baby boy was taken away from her.

Johnson recalled crying as she had to leave her newborn son all alone in a nursey. The most worrying thought she had in mind was whether her partner at the time was allowed to take care of their son, since they were not married.

When she got back to the prison, she began to breast pump in order save up milk for her child.

Later she was informed that her five-month-old son was diagnosed with leukemia, so she was allowed to see him once a month and was able to breastfeed him during parent-child visits. She became diligent about breastfeeding.

However, after seven months, the prison asked her to stop breastfeeding. This was around the time that her son began feeding through a nasogastric tube. According to Johnson, he had tried to feed through formula. However, he was highly allergic. She had to get Boston Medical Hospital to write a note saying that breastfeeding was a medical necessity.

When she finally got out of prison, she was asked by the Prison Birth Project to speak and tell her story at the Massachusetts State House where now former Governor of Massachusetts Deval Patrick signed an anti-shackling law.

Dr. Melody Slashinski then spoke on her work as a researcher in the public health sciences, where she is dedicated to find the root cause of the mass incarceration rate, which she believes feeds into a culture of patriarchy.

Slashinski discussed how despite the fact that majority of prisoners are men, women inmate rates have increased over 700 percent since the 1980s. The rate of women prisoners in the 1980s outpaced the rate of men by half.

Slashinski believes that in order to end criminalizing gender and race, we must believe that these attitudes are changeable.

Lastly, Kim Gilhuly who is part of the Human Impact Partners’ “Health Instead of Punishment” program, spoke on the four parts of her program, research, advocacy, capacity and action alliances.

“I knew women had issues in the prison system but I didn’t really see how they were really degraded and how they were taken from their families and how it impacted their kids,” said Marieflor Bauzon, a first year graduate student studying public health.

“I think it was a great event. There were really important issues to be reminded of and you just have different ways of looking at the issue and it’s an issue that really needs to be kept in the forefront and as public health professionals, we need to remember that these are public health issues” said Laura Kittross, a Berkshire Regional Planning Commission Public Health Manager.

“I thought it was great. It was a really, really great event. We talked about a lot of important issues, I really appreciated the fact that Andrea definitely naming the fact that prison abolition is something that we should striving for,” said Nathalie Amazan, a sophomore political science and legal studies double major.

Alvin Buyinza can be reached at [email protected].