On July 17, 1971, President Richard Nixon declared a “War on Drugs” and cited drug abuse as “public enemy number one.” We are more than 40 years removed from Nixon’s executive declaration, which he signed into law in January 1972. At the time, he was quoted by Adam Raphael of the Guardian as saying, “I am convinced that the only way to fight this menace is by attacking it on many fronts.” But what might have started as an attack on the problem of drugs has led to an ongoing attack on people instead.

Of course, such militant language when confronting national emergencies was nothing new at the time. Nixon didn’t need to look further than his predecessor, President Lyndon Johnson, and his 1964 “War on Poverty” for historical precedent. Some 30 years later, John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s White House domestic affairs adviser, admitted to Harpers that the initiative was a deliberate way to target Black people and hippies by enforcing stricter penalties for heroin and marijuana use. Nixon’s passage of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 sought to do just that. Marijuana was declared a Schedule I drug, believed to be as dangerous as heroin and other opioids that same year following the passing of the Controlled Substances Act.

The heroin epidemic that engulfed much of the Black community in the 1960s was dealt with similarly to violent crime. However, this country’s current opioid epidemic is understood as a ‘disease.’ In declaring the opioid crisis a “public health emergency” just a month ago, President Trump said that in order to help reverse the downward spiral of further opioid addicts, there is going to be “really tough, really big, really great advertising.” Perhaps more should not be expected of our current president. Given his background and extensive experience in the advertising world, it probably makes sense that combating such a crisis from a business point-of-view is more understandable for him. As the New York Times piece says, such phrasing beckons back to Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign, which helped assure the Anti-Drug Abuse Act that was passed by Congress in 1986 and imposed mandatory minimum sentences for low-level drug offenses.

“Just Say No” ushered in high incarceration rates. Beginning with Reagan and continuing with George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, “the number of people behind bars for nonviolent drug law offenses increased from 50,000 in 1980 to over 400,000 by 1997.” Programs like DARE, founded by Los Angeles Chief of Police Daryl Gates, helped perpetuate this process of mass incarceration in inner-city neighborhoods, which again resulted in a rapidly growing prison population. The ‘crack’ epidemic of 1980s can also be seen upon racial lines. While, statistically speaking, Black people were no more likely to use or possess the drug than whites, those who “possessed” a small amount of crack would get the same prison sentence as whites possessing “a quantity of cocaine that is 100 times larger.” Such selective sentencing should be seen as discrimination, not sound decision making.

If the current path persists, the heroin epidemic will squander the crack-cocaine epidemic of 30 years ago. Of the some 64,000 people who died of drug overdoses in 2016, roughly 50,000 were from opioids. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, of all the opioid overdose deaths that took place in the United States in 2015, approximately 82 percent of the deceased were white. Criticism of this statistic will include stark differences in population between white and Black people. While it is true that this most recent epidemic has affected whites on a larger level, especially in rural areas of this country, it is worth looking at this issue through racial lines. As Ekow N. Yankah pointed out in a recent opinion piece for the Times, one of the reasons that opioid death amongst Black people don’t mirror the mortality figures of whites has to do with the under-prescription of opioid painkillers for Black people. According to research drawing on data from the National Ambulatory Medical Survey, non-Hispanic Black people “were half-to-two-thirds less likely to receive opioids for back or abdominal pain than non-Hispanic whites.” A study conducted at the University of Pennsylvania found similar racial disparities in pain prescriptions.

There is an interesting bipartisan initiative taking place in response to the current epidemic. Politicians representing 24 states, including the District of Columbia, have put laws in place that makes the prescription drug naloxone, a prescription drug used to combat the effects of heroin overdose, more widely accessible to the general public. Republican Ohio Governor John Kasich even went as far as to as to sign in “emergency legislation,” making the drug available without a prescription.

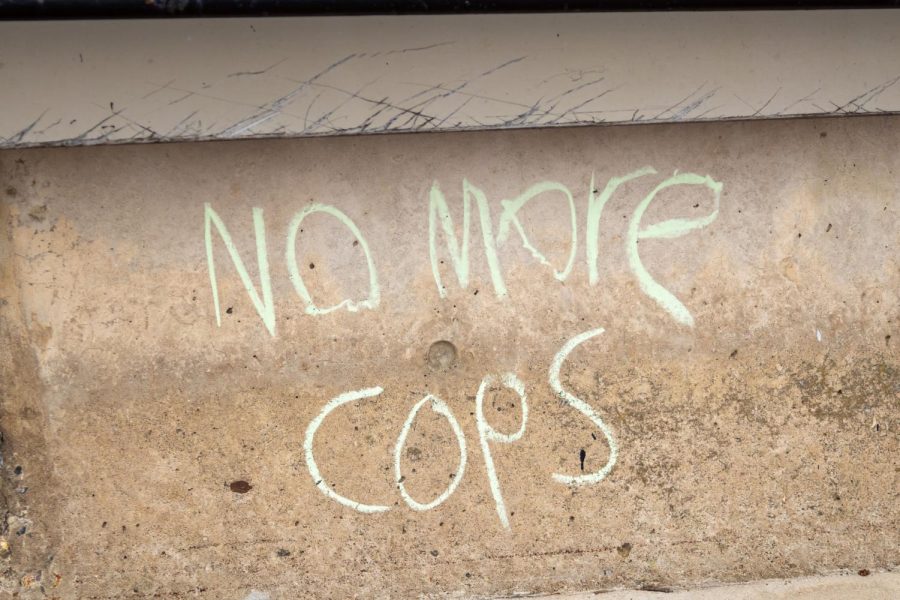

In the 1980s, the problem of crack cocaine was understood and fought in a disciplinary manner, rather than as a disease suffered by individuals. This difference in language has informed changes in policy. The existence of sensible drug policy is what our society needs. What has existed are racist policies that permeate Black culture at rates disproportionate to that of whites, not because they use more drugs, but because of selective enforcement. The opioid crisis facing this country should be treated as an epidemic, but when prior addicts are treated as criminals and current ones are treated with compassion and care, we must understand the apparent double-standard at play.

Isaac Simon is a Collegian columnist and can be reached at [email protected].

NITZAKHON • Nov 28, 2017 at 1:05 pm

Dunbar High School After 100 Years

http://www.frontpagemag.com/fpm/264391/dunbar-high-school-after-100-years-thomas-sowell

Quote:

“In 1899, when it was called “the M Street School,” a test was given in Washington’s four academic public high schools, three white and one black. The black high school scored higher than two of the three white high schools. Today, it would be considered Utopian even to set that as a goal, much less expect to see it happen.”

So what changed? Because one cannot – at least not with a straight face – argue that America in 1899 was less racist than 2017. It is the culture, it is the culture of fatherlessness and thuggery created by the Democrats, and perpetuated and glorified by (left-leaning) Hollywood and the media.

What a shame – a proud and capable people, blacks, re-enslaved by the Left even as the Left beats its chest about how it’s “helping”.

NITZAKHON • Nov 28, 2017 at 10:30 am

You might also consider that rampant fatherlessness, as deliberately created by LBJ to create a permanent Democrat-leaning and dependent-on-government black population, is at fault.

The True Black Tragedy: Illegitimacy Rate of Nearly 75%

https://www.cnsnews.com/commentary/walter-e-williams/true-black-tragedy-illegitimacy-rate-nearly-75