George Carlin artfully describes the objective of football in a 30-second clip: He jokes, “In football, the object is for the quarterback, also known as the field general to be on target with his aerial assault…With short bullet passes and long bombs, he marches his troops into enemy territory, balancing this aerial assault with a sustained ground attack that punches holes in the forward wall of the enemy’s defensive line.”

As an avid football consumer, I can honestly say that I’ve heard multiple versions of similar rhetoric repeated by broadcasters and, once removed from adamantly watching ‘Tommy Terrific’ reaffirm his G.O.A.T. legacy, the rhetoric comes across as undoubtedly aggressive. Is it fair to draw similarities between football and war? War is an atrocious, albeit sometimes necessary, aspect of global politics, and football is the reason I wake up before 1 p.m. on Sundays. However you might feel about the comparison, the United States military has a very particular stance of its own.

Since the start of the 21st century, the U.S. military has clearly demonstrated a vested interest in creating a strong connection between the armed services and football. A U.S. Senate report from 2015 unearthed that the military services spent $53 million on marketing and advertising contracts with sports teams between 2012 and 2015. More than $10 million of that total was paid to teams in the National Football League. The Department of Defense paid teams to include an on-field color guard during the national anthem, hold enlistment and reenlistment ceremonies, perform the National Anthem and have full-field flag details. The National Guard also paid teams for the “opportunity” to sponsor military appreciation nights and to recognize its birthday. They additionally paid the Buffalo Bills to sponsor its “Salute to the Service” game. The DOD even paid teams to perform surprise “welcome home” promotions for troops returning from deployments and to recognize wounded veterans. Such a costly investment in trying to display patriotism and dedication to service in the NFL prompted senators to find a motive, and the military justified its venture by rationalizing that it would help them find the “recruits” for the DOD.

Still, the military hasn’t stopped there to assert its clout on the gridiron. They’ve gone so far as to lie to NFL fans and the United States about the service records of former players to shield their marketing narrative.

Pat Tillman was a safety for the Arizona Cardinals until he joined the military directly after 9/11 to protect his country. After his death, the military told Tillman’s family, and the world, that he was killed in a shootout with the enemy and awarded him a Silver Star for his “gallantry in action against an armed enemy.” Tillman was heralded by the NFL and sports media as “a true American hero,” and pregame ceremonies honoring his valiant death were held across the league. Fox NFL Sunday even held its weekly morning football show from Tillman’s old base, repeatedly paying homage to his sacrifice and passion to serve.

However, a few weeks after Tillman died and a majority of the press attention subsided, the Army recanted its original story to the family and told them Tillman was killed by friendly fire. Thereafter, Tillman’s mother began her own investigation into her son’s death and sat down with “60 Minutes,” revealing a series of duplicitous cover-ups from the military to conceal the true cause of Tillman’s death. Perhaps most shockingly, friends close to Tillman who knew he had lost his enthusiasm for the war before his death revealed that he had repeatedly expressed “fear that if something happened to him, his death would be exploited by the military and used as propaganda.” To be fair, the exploitation of Tillman’s death is a singular occurrence, but the military has glorified other NFL players that have served or are otherwise connected to military. Players have been featured in commercials for the military’s insurance group United Services Automobile Association, and have spoken in public service announcements during “Salute to Service Week,” further aligning the NFL with the DOD.

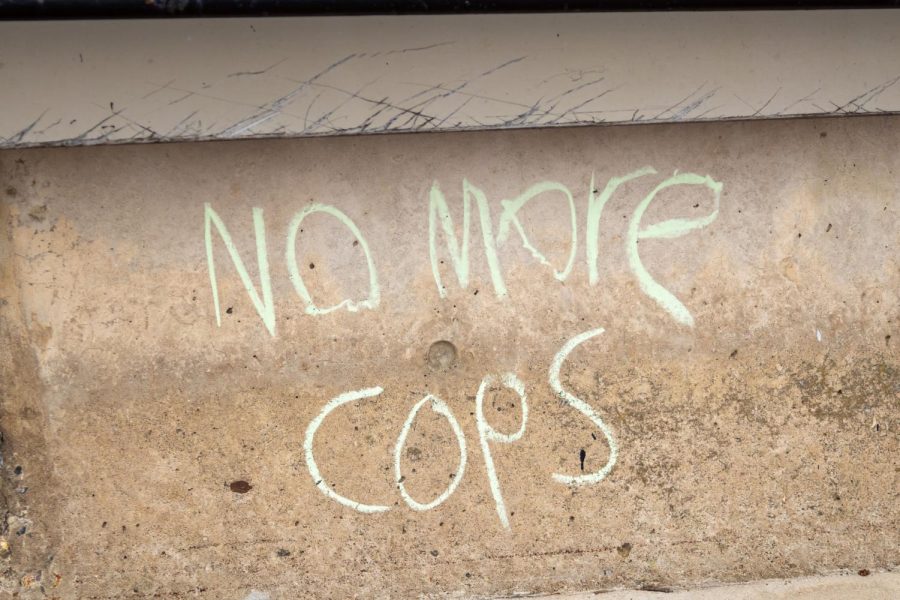

Writing this on Feb. 2, I’ll bet $100 that before the Super Bowl this weekend, there will be a lavish ceremony honoring the National Anthem with soldiers coming out to hold a giant, field-sized flag, raptor jets flying over the stadium and a trained bald eagle soaring down from the rafters. I’ll bet my college tuition that Uncle Sam helped pay for it. I don’t think football is war, but it’d be imperceptive to doubt that the military purposely markets itself as an alternative for those who can’t get on the gridiron. So, next time you think about the NFL and its social issues—like kneeling protests during the national anthem—consider that there may be a lot more riding on it for the NFL than losing some viewers and getting a few boos from the stands.

Henry Dowd is a Collegian contributor and can be reached at [email protected].