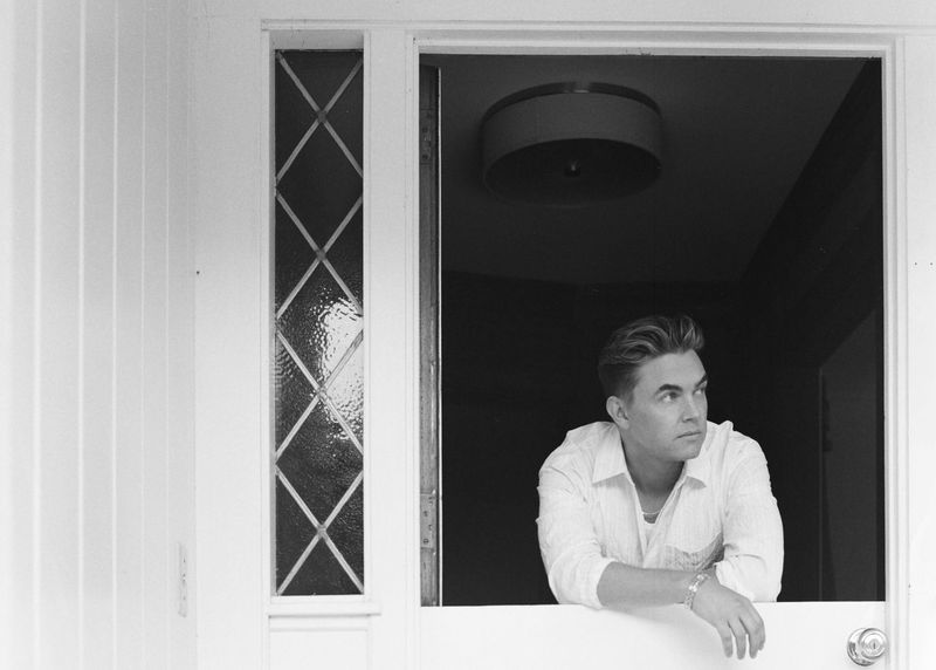

One hundred days after the impeachment investigation into Student Government Association President Timmy Sullivan was announced on Oct. 30, the student judiciary closed a hearing on Sullivan’s possible recall at 12:18 a.m. on Saturday, Feb. 8.

The hearing took place over two sessions on Thursday and Friday evenings, lasting more than 11 hours in total. Within 48 hours of the end of the hearing, the six justices are required to enter a deliberative session. According to SGA bylaws, the session shall be closed and held in confidence at all times. No more than five school days from the closing of the deliberative session, the judiciary will issue the written majority ruling and any dissenting opinions, as required in the bylaws.

As the remnants of the audience began packing up to leave early on Saturday morning, SGA Chief Justice Aditi Joglekar and Associate Chief Justice Koray Rosati explained that a previous hearing in the 2019-20 academic year had a deliberative session that lasted around an hour. Rosati quickly added this precedent-setting case, the first recall hearing for an SGA president, would require more time.

“It will definitely be a lengthy deliberative argument,” Joglekar said.

The majority ruling will be based only upon evidence or testimony introduced at the hearing or in the submitted brief. This includes the testimony of 12 witnesses, numerous documents submitted by both the petitioner and respondent and hours of questioning.

The session opens: Thursday, 6 p.m.

On Thursday, Feb. 6 at 6 p.m., Joglekar convened the hearing in the Integrative Learning Center at the University of Massachusetts. The first session, which lasted just over four hours including recesses, included the opening statement by the petitioner and the presentation of five witnesses.

The petitioner, the SGA senate, was represented by four senators: Jordan McCarthy, Sean Vo, Patrick Collins and Nicholas Flanagan. McCarthy announced he would be among the representatives in the SGA meeting on Wednesday, Feb. 5, saying, “We spent a lot of time and effort creating an extremely exhaustive brief for our case . . . we’ve provided that to the judiciary and they accepted it.”

The respondent, Sullivan, was joined by his judicial advocate, Ilina Shah. Shah, the attorney general of the SGA, announced her decision to serve as judicial advocate in a statement that was read at the Feb. 5 meeting. Shah was interested in the precedent the case would set and made her decision based on “[her] understanding of what is right, according to the constitution, bylaws and the existing precedent.”

Approximately 50 people were in the hall at the start of the session and several rose to be sworn in as witnesses, including Administrative Affairs Chair Althea Turley. During the opening statements, Turley spoke alongside the senate petitioners, a move later questioned by the respondents as Turley was not announced during the Wednesday senate meeting. The judiciary moved past the debate, stating it was a matter for the senate to deal with.

Sullivan asks a procedural question about the previous night’s SGA meeting as one of the Senate members speaking was not included in the chosen representatives. Judiciary said that is a matter for the senate to discuss.

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 7, 2020

The case of the petitioners

McCarthy delivered a majority of the opening statement, claiming that Sullivan was an “ineffective leader” and had allocated additional pay to his own bank account between February and April of 2019. McCarthy referenced two articles of impeachment passed by the senate in December 2019.

As reported by the Collegian, the first article focused on Sullivan’s failure to submit a nominee for vice president to the senate within 30 days of former vice president Nathalie Amazan’s resignation. According to the article of impeachment and the subcommittee report, Sullivan began receiving an additional 10 hours of pay during the pay period beginning on Feb. 3.

McCarthy, who was chair of the rules and ethics subcommittee, repeated many of the allegations from the report during the opening statement. He noted that Sullivan did not tell the senate about the change in how funds were allocated in the executive branch and that Sullivan continued logging 30 hours per week after a new vice president, Hayden Latimer-Ireland, was sworn in on April 1.

The second article of impeachment referenced by McCarthy cited vacancies in two cabinet positions: secretary of technology and chief of staff. As reported in December, Sullivan chose not to fill the positions and these decisions were not reported to the senate. On Oct. 30, Sullivan incorrectly stated there were no applicants, later telling the subcommittee that he “misremembered.” Two applicants were received for each position. The articles of impeachment stated the president didn’t notify all applicants of their acceptance or rejection, which is required under the bylaws. Impeachment, McCarthy said, was “necessary” and “valid.”

During the opening statement, McCarthy stated a public records request had unveiled new evidence to the petitioners on Wednesday. It was later revealed that this evidence was the names of the four rejected applicants. While there was a brief debate about the relevance of the names and whether new evidence could be submitted, Sullivan ultimately stated the names on the record during his questioning on Friday night.

The petitioners claimed Sullivan had committed “manifest injury” to the student body, as the funds concerned in the case came from the Student Activities Trust Fund which is supported by student fees. While the senators did not present all of the evidence from the meeting where impeachment took place, they answered several questions from the judiciary about the purpose of the hearing.

McCarthy claims the “manifest injury” is financial as the “mis-allocated” funds in question came from a student-supported fund. @MDCollegian

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 7, 2020

In his remarks, McCarthy argued that procedures for impeachment had been followed from the submission of a petition to investigation to impeachment to the hearing. As the hearing was the first of its kind in the SGA, the judiciary asked all relevant parties what the judiciary should be making their decision on. Petitioners said the judiciary would rule on “constitutionality and validity,” focusing both on the acts committed by Sullivan, the evidence from the investigation and the impeachment of the president.

“Maybe this case will be referenced in the future, I’m sure it will be,” McCarthy added, noting how there is no clear precedent for the impeachment process.

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 7, 2020

The senate’s petition to the judiciary came under scrutiny early in the hearing and was repeatedly questioned by both the judiciary and respondent. While based on the articles of impeachment, the petition was not a “copy and paste” of the exact language voted on by the senate. The articles were included in the materials submitted to the judiciary.

Turley said that one conversation, in which Sullivan allegedly misled the subcommittee regarding a conversation with SGA adviser Lydia Washington, was not mentioned in the original articles but influenced the senate’s vote for impeachment and was relevant.

The first question from a member of the judiciary concerns the Senate’s petition and whether the articles of impeachment were quoted. McCarthy has not answered a “yes” or “no” and there seems to be confusion over what the petition needed to include. @MDCollegian

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 6, 2020

The respondents, Sullivan and Shah, were granted time to question the petitioners and the conversation turned to what “act” the judiciary needed to rule on. Turley insisted the context of impeachment was important. The conversation focused on a bylaw saying the petition must be filed within 90 days of the action committed by an SGA official. Turley argued the “act” was the impeachment by the Senate.

Turley added that the petition was more inclusive than the articles of impeachment in the interest of “brevity” when an associate justice cited the disconnect between the lengthy presentation of evidence and only six points in the articles.

The witnesses of the petitioners: Thursday, 8 p.m.

At 8:01 p.m., approximately two hours into the session, the first witness was called by the petitioner. Jake Binnall, the former secretary of the registry and the current student trustee, had been present for the opening arguments and was sworn in earlier in the evening, allowing him to take a seat before the judiciary.

The first question was about Binnall’s workload as secretary of the registry, which he said was “over 15 hours” pretty much every week. “That was just the job,” Binnall added.

The petitioners played an audio clip of Sullivan’s statement at an Oct. 30 meeting about his choice to submit 30 hours and how the change was “normal and procedural.” The petitioners asked Binnall about how allocation of pay operated in the Sullivan cabinet the previous year.

While he worked on campus during a summer break on behalf of the SGA, Binnall said his request for compensation was denied but he was still required to complete work. After questioning from the justices, Binnall clarified that Sullivan did not order him to complete tasks outside of his position but stated there would have been “harmful consequences” if he had not completed the tasks.

“Backpay was not something I was told we were allowed to ask for,” Binnall said in response to a question over whether he could receive the funds after his summer working as Secretary of the Registry.

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 7, 2020

The second witness for the senate was Turley, who spoke about her role as chair of administrative affairs. Stating that she had read the bylaws at least twice in their entirety, Turley drew a distinction between new allegations and new evidence.

“No new allegations are being levied,” Turley said. “It’s all about explaining why it was egregious that the bylaws were broken.”

Shah questioned Turley about the logic of claiming that information from the presentation about impeachment charges was included in the petition. The attorney general pointed out that a club making claims in their presentation were not necessarily relevant to the club’s motion voted on by the senate. Turley said the hypothetical situation did not compare to the impeachment process, as the presentation by rules and ethics was substantiated by documentation and evidence.

“The whole presentation cannot be separated from the articles of impeachment,” Turley repeated.

Incumbent vice president Latimer-Ireland was called as the third witness concerning her first few months in office. Latimer-Ireland stated that she was not paid for the month of April by her own fault as she did not fill out the necessary paperwork due to needing documents from home and completing her finals.

“It is the responsibility of the officers to submit their own paperwork,” Latimer-Ireland said. She said that during the transition period where new and old administrations overlap, Sullivan was still fulfilling duties of the vice president.

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 7, 2020

The vice president stated that “there has always been that transitional period when two people are logging pay.” While she did not receive pay for her work, she stated again that she hadn’t turned in her paperwork. She said she was not aware of how many hours Sullivan was reporting.

Latimer-Ireland answered several questions about her duties as vice president, explaining that there are no bylaws stipulating the position’s role. Instead, the vice president’s role is determined by its holder and the president they serve under, something Amazan and Sullivan spoke about in greater depth on Friday night.

The fourth witness was the chair of the Ways and Means Committee, Amelia Marceau. According to Marceau, the president is allocated 20 hours per week in the SGA budget and Sullivan “requested more pay than he was allocated.”

Turley asked Marceau if it was “normal and procedural” for someone to go beyond that allocation and Marceau said it was not.

“The standard is that everybody is getting paid for what they’re allocated for,” Marceau added.

Sullivan asked Marceau why she had accused him of “criminal activity” in an earlier SGA meeting. Marceau stated she could not say anything about that. In response to a question from Shah about whether Sullivan completed the work, Marceau stated she was not on campus at the time and could not testify to that.

Chantal Barbosa, a former SGA vice president and a current employee of the Student Organization Resource Center, was called as the final witness by the representatives of the senate.

Barbosa, who served as vice president in the 2015-16 academic year, spoke about how her administration had held cabinet officials accountable for completing work.

“If the administration doesn’t have a way to hold their cabinet accountable, how is the adviser supposed to do that?” Barbosa said. Based on her experience as vice president, Barbosa said Sullivan had violated bylaws. The justices questioned Barbosa’s expertise with the constitution and bylaws, given the amount of time that had passed since she had been in office.

At 10:13 p.m., the petitioners rested their case. Joglekar called a recess and stated the session would be opened again within 72 hours.

Friday night

At 5:30 p.m. on Feb. 7, the judiciary reconvened in the basement of the Campus Center to hear from the respondents. Fewer people attended the second portion of the hearing, with the number declining as the second session lasted nearly seven hours.

Shah, the judicial advocate, delivered the opening statement for the respondents, saying she was “not here to simply play lawyer to President Sullivan.” She spoke about her experience as attorney general and holding the president accountable, as well as her experience working on the investigation.

Shah took issue with the fact that the language of the petition differed from the language of the articles, arguing the vote had been on the articles, not the presentation. Rather than procedure, Shah said the judiciary should look at “underlying facts.”

McCarthy asked if Shah would provide any evidence exonerating the president from the allegations and she replied in the affirmative. Rosati reminded McCarthy it was the petitioner’s burden to provide proof, but McCarthy said he still wanted to know.

Shah explained the case also focused on the statute of limitations, as she did not believe the “act” was the impeachment. She argued that if the impeachment was the act, it was the senate who committed it and they would be the respondent rather than the petitioner. Sullivan later reasserted this claim.

The lack of precedent in today’s case has led to a debate over what the judiciary should be ruling on. Sullivan says the judiciary should be ruling on the actions of the respondent (himself), not the constitutionality of the process of impeachment (what the senate did).

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 8, 2020

The respondents addressed the petitioners’ claims that the discussion held in the senate was part of the impeachment, with Shah saying the presentation and debate informed the vote but it was not what was being voted on by the senate. Shah also alleged that Sullivan was not given adequate time to prepare for responding to the articles of impeachment and denied that it was her responsibility to inform Sullivan. McCarthy stated that all evidence of the rules and ethics subcommittee was available to Sullivan.

“Anyone who is impeached should have that specific language before they’re on the podium,” Shah said.

Sullivan added that the “discrepancy” between the language of the articles of impeachment and the petition was a violation of due process. Turley responded to a question from Associate Justice Michael Devlin-Horne to state the language was changed to be more direct.

For the respondents, it was a question of who had the authority to write the petition and deliver it to the judiciary. While the bylaws state it is the senate, the petitioners claimed it referred to the subcommittee of rules and ethics who led the investigation. The senators chosen to represent the senate in the hearing were from the subcommittee, who had conducted the investigation. Shah said the senate should have voted on and passed the language of the petition.

“Even the tiniest grammatical issue; we have to vote,” Shah said.

Sullivan spoke about vacancies in the cabinet and quoted from an email written from the subcommittee to himself during the fall semester. A vacancy which had occurred in the cabinet in the secretary of veterans affairs position represented a similar case to vacancies in the spring semester, Sullivan argued, and he had followed the procedure advised by the subcommittee. Members of the judiciary interrupted to state that questions of fact were more suited to witness questioning, not questioning the petitioners.

After a brief recess, Sullivan and Shah presented their witnesses, starting with Latimer-Ireland. She recalled when her application for vice president was not accepted the previous spring, explaining it was a decision between herself and Sullivan. Since the ratification of the spring election had been delayed, the two agreed not to nominate Latimer-Ireland to avoid the then-freshman senator from preemptively losing her senate seat or only being sworn in to serve a week.

“We decided that given the timeline, and the fact that I could be effectively losing my vote . . . it would have taken up a lot of time that could have gone to other things,” Latimer-Ireland said.

Latimer-Ireland also answered questions about her duties in office, saying there was a lot of overlap between her work and Sullivan’s. The differences, she explained, came not from their difference in interests.

The second witness for the respondents was Sonya Epstein, the secretary of university policy and external affairs in Sullivan’s cabinet. Epstein confirmed their presence at the Oct. 30 meeting when the impeachment investigation was announced but did not recall if they were there for the entire meeting. Epstein also confirmed that they witnessed Sullivan’s large workload from last spring, when he had been reporting extra hours.

Senator Barkha Bhandari, who works on the Food Justice campaign with Sullivan, was the third witness. She stated that Sullivan was very involved in the project and had a lot of demands on his time. Through questioning, Sullivan established that if he hadn’t dedicated time to the project after Amazan’s resignation, it could have compromised the project. “When Vice President Amazan resigned, in order to maintain the integrity of these projects, 50 percent of the workload essentially became mine,” said Sullivan.

McCarthy asks Bhandari about the relevance of her answers to the impeachment case. She replies she is just answering the questions she is being asked and that she is testifying to the amount of work Sullivan performed.

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 8, 2020

The fourth witness was Amazan, who said that her collaboration with Sullivan was based on the pair’s shared interests. Sullivan and Amazan confirmed they adjusted pay hours to ensure they received the same amount of hours each week to represent their working relationship. The previous standard was that the president got 20 pay hours per week and the vice president got 15. Sullivan and Amazon adjusted this so that they each got 17.5 hours per week.

Amazan also vouched for Sullivan’s character in terms of the allegation that he took unwarranted extra pay: “It wouldn’t make sense for him to just take the money for his own personal gain,” she said.

Amazan testifies to seeing the projects continue after her “retirement” – a phrase which caused a bit of laughter on Sullivan’s side of the room – and said she felt Sullivan completed additional work. Judiciary asked if she had seen evidence and Amazan stated she was not present.

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 8, 2020

The fifth witness called was Shah, who brought up several previous cases in SGA history that she believed set precedent for Sullivan’s case. None of these cases were impeachment cases, because Sullivan’s is the first known case in SGA history. “Certainly the judiciary rulings that I researched are for a different context . . . but I believe at the time, in the absence of specific precedent, they still offer useful guidance,” said Shah.

In Shah’s testimony, she also alleged that the rules and ethics subcommittee could have held inherent suspicions of Sullivan going into the investigation, and that these suspicions could have affected the subcommittee’s work. To give an example of the alleged issues she had seen within the subcommittee, Shah described an instance in which Sullivan had come close to failing to respond to a records request within the allotted time frame. Shah said that when she suggested reminding Sullivan of the deadline, she was met with opposition from the subcommittee. “The question that came to my mind was . . . ‘why would helping someone comply with the bylaws be worthy of accusation and suspicion?’” said Shah.

Shah believed that working on the subcommittee was not a conflict of interest, given that it was an ex-officio role and she was “making sure the integrity of the investigation was not compromised in any way.” Shah could not vote on the final decision to impeach.

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 8, 2020

The president served as the sixth witness for the respondent. Answering questions from Shah, Sullivan stated there were no bylaws for payroll and that his additional labor hours were for the role of vice president. He did not recall seeing the recommended allocations in the budget but was aware of what his predecessor was paid.

When asked about how hours were approved, Sullivan said he was not able to approve his pay. From his understanding, the hours were submitted to the SGA adviser.

“I really don’t know what happens after I submit [the hours],” Sullivan said. “That’s above my pay grade.”

Sullivan also spoke about the “hyper-visibility” of his role. While doing work for the secretary of technology was less visible to the community, he said his additional work in the role of vice president on the administration’s projects caused him to feel like he was “always performing.”

When the issue of informing applicants of their rejection came up – a alleged bylaw violation – Sullivan said he chose to notify applicants in person. Latimer-Ireland and a secretary of technology applicant, he explained, were already present in his life and he saw them every day, so it made sense to tell them himself. He added it was “by chance” he saw the other vice presidential applicant and thought it was better to inform him in person.

According to Sullivan, the other secretary of technology applicant shared a mutual friend and asked the friend to inform the rejected applicant. Sullivan did not know if the request was carried out and the mutual friend has since graduated and did not supply a written testimony. Sullivan said the friend only vaguely remembered the conversation.

Collins asked Sullivan about the relationship between the rejected vice-presidential candidate – not Latimer-Ireland – and himself. Sullivan said he knew the individual and had informed him of the rejection in Franklin Dining Commons prior to March 6.

Sullivan also clarified his use of the term “normal and procedural,” which had been played in an audio file the night before. He said it referred to his role of overseeing the work and pay of his cabinet members.

During his answers, Sullivan took issue with the “culture” of the SGA, saying that some work – specifically financial and budget-focused work – is more easily justified by the organization than the work he performed on projects like college affordability.

Sullivan cited his involvement on college affordability and other administration projects and claimed that his additional hours were being challenged in a way that Former Speaker Mahan’s hours for work on the budget were not.

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 8, 2020

The petitioners’ questions focused more closely on Sullivan’s choice to enter 30 hours per week, asking about his meeting with the SGA adviser. Sullivan could not remember details of the meeting, saying it was probably in Washington’s office in early February. He stated he did not remember what the SGA adviser told him in that meeting, just that he informed her of his choice to increase his hours.

When asked about “misremembering” the applications for secretary of technology, Sullivan said the events had happened a year earlier and he had many things going on at the time, including a re-election campaign. Speaking about the spring 2018 semester, Sullivan said he could not delegate the work to other positions due to bylaws restrictions.

Sullivan said that the decisions, including Amazan’s resignation and Latimer-Ireland’s delay in hiring, made in the semester were negative for him and his workload but were the best decisions for others.

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 8, 2020

When asked about reporting the work he did, Sullivan said he only asked for “accountability logs” from his staff. The logs are used for goal setting and management purposes, Sullivan explained. Since he was aware of his own work, he did not complete logs.

Sullivan appeared to be the last witness until Brum asked if any witness was going to come forward to talk about how payroll actually works. Pointing out the case involved “real money” coming out of an account, Brum said, “Nobody’s going to be able to explain who approves these hours?”

Washington, the SGA adviser, was present in the room and was called specifically to answer questions related to payroll, per the request of the Judiciary. In her interview, Washington stated “I can’t decline hours because it’s against the law.” Washington was also very clear that she only wanted to address questions related to payroll.

“Does the University of Massachusetts Amherst have any rules or procedures that you make sure that work is being done and that money is being spent responsibly?” Justice Brum asks.

“I don’t know how to answer,” Washington said, explaining that she is not able to reject hours.

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 8, 2020

Washington said she told Sullivan that it was his decision to increase his hours as he was president. Her role, she stated, was to make sure the SGA didn’t go into the negative in the budget.

“I just want to talk about payroll, I don’t want to get involved in y’all’s drama,” Washington shook her head when questions went beyond the topic of payroll.

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 8, 2020

After the respondent rested their case at 11:21 p.m., a brief recess was held. Joglekar stated that each side would have 30 minutes to give their closing statements but reminded them they were not required to use the full time.

During their closing statement, Shah was questioned further by the Judiciary about the precedent from earlier SGA cases that she had referenced in her testimony. During the line of questioning, the judiciary mentioned that none of these cases were recall cases. Shah responded that while the circumstances were different, they could still help the judiciary to make a decision.

“I believed that the level of actions were similar, but I absolutely agree that it is not direct precedent,” she said.

“What do you believe that precedent should be?” Brum asks Shah, who says she is “hesitant” to answer that.

“I genuinely believe if this recall goes through, that would undermine the constitution and bylaws,” Shah said, referencing the change in language in the petition.

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 8, 2020

Shah was also questioned about her interpretation of the 90-day statute outlined in the bylaws. By Shah’s interpretation of the statue, no evidence that was over 90 days old could be considered in the Judiciary’s decision: “The 90 day statute is very clear;” she said. “If people want to change that, that would have to be a constitutional amendment.”

Shah ended the respondent’s closing statement by admitting that Sullivan did break some bylaws but went on to argue that he broke them ethically, and that the act of breaking a bylaw alone should not warrant impeachment.

The petitioners began their closing statement with McCarthy’s argument that the 90 day statute refers to the action of impeachment itself: “The only action that causes us to be here tonight for a recall hearing is an impeachment,” McCarthy said. He went on to restate his argument that any evidence used in the impeachment trial should be considered by the Judiciary, as it affected the senate’s original vote to impeach: “I think you should be looking at all the facts that went into the senate’s decision to impeach, because that was the information they had,” he said.

McCarthy went on to argue that the role of the judiciary is to determine if the impeachment itself was constitutional and valid.

“Judiciary is changed with determining the constitutionality and validity of the action . . . that’s the entire point of the judiciary hearing,” said McCarthy.

McCarthy also argued that Sullivan had not only broken the bylaws, but that these violations were unethical. He argued that the precedent set for future recall hearings should follow the standard that “if a bylaw is broken and it is unethical, then the officer should be impeached.”

Addressing the earlier conversation about whether the senate should have created the petition, McCarthy pointed out Speaker Rachel Ellis intentionally removed herself from the process. Ellis would become president if Sullivan was removed.

The hearing enters a third day at 12:00 a.m. on Saturday morning. pic.twitter.com/WFdM9ng837

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 8, 2020

McCarthy also argued that Sullivan’s decision to pay himself over 20 hours per week was unethical because of his failure to appoint an applicant to the unfilled position: “if he did the work he should be paid . . . however, to continue to pay yourself when you had applicants is unethical,” he said. McCarthy went on to clarify that “we are not arguing that Sullivan should not have been paid for his work.”

McCarthy ended the closing statement by arguing that any unethical personal financial gain should warrant a recalling of a president, no matter how large or small the amount.

The hearing enters a third day at 12:00 a.m. on Saturday morning. pic.twitter.com/WFdM9ng837

— Kathrine Esten (@KathrineEsten) February 8, 2020

The meeting was adjourned at 12:18 a.m. after Joglekar spoke about the appeals process, which can only take place under specific circumstances including new evidence.

While no decision has been announced, several outcomes remain possible. If a majority ruling is not reached, the actions of the respondent, Sullivan, shall be allowed to stand and no action will be taken. If the majority ruling is in favor of the petitioner, Sullivan will be recalled from office and Ellis will be sworn into the presidency until the end of the term in April. If the majority ruling is in favor of the respondent, Sullivan will remain in office.

Kathrine Esten can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter at @Kathrine Esten. Sophia Gardner can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter at @sophieegardnerr.