Always underrated, Isaiah Rodgers is ready to show everyone what they’ve been missing out on

"He was a no-brainer from the day he stepped on campus"

April 22, 2020

When Isaiah Rodgers, the only boy in his family, was three years old, he was always searching for someone to play football with.

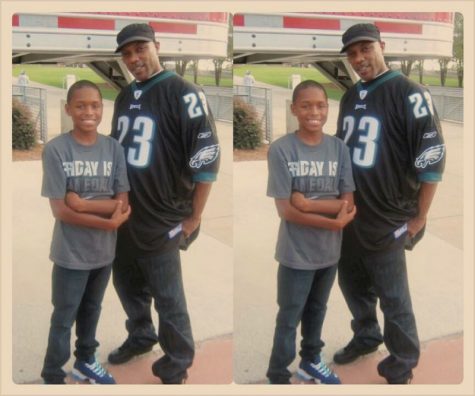

His first choice was his older cousin, Dominique Rodgers-Cromartie, who was always playing backyard football with his friends. Isaiah would walk over to them and tell his cousin that he wanted to play with them, but Rodgers-Cromartie and his friends were 10 years older than Isaiah and a lot bigger. Rodgers-Cromartie would quickly turn him down, telling Isaiah that he would have to play with the younger kids.

This annoyed Rodgers, who was disgruntled to have to settle for the neighborhood three-year-olds – he wanted to play tackle football with the big kids.

19 years later, Isaiah Rodgers finished off his record-breaking collegiate career for the Massachusetts football team – and now he’s looking for a shot to move up.

Even at five, Rodgers was no exception in his household when it came to chores. He helped out with the dishes, cooked and was the “trash guy” of the family. The trash guy role even progressed over the years to the point where Isaiah would take everybody’s trash out in his neighborhood to make a little money.

“As a mother of multiple children, I didn’t play,” Kelly O’Neal, Rodgers’ mother, said. “I did not tolerate disrespect and not taking care of your responsibilities at home, because then outside of the home you’ll disrespect people and you won’t take responsibility for your actions.”

Isaiah’s father, Craig Rodgers, taught his son about what the duties of being the man of the house included. Isaiah had to learn sooner than anticipated, as Craig and Kelly divorced when Isaiah was 11 years old.

This didn’t affect Isaiah much, as he continued playing football throughout elementary school, but when looking at Rodgers, one thing was clear: he was tiny, so small that he didn’t top the 5-foot mark until his sophomore year of high school. Even with his size an obvious disadvantage on the football field, Rodgers was still able to make it work.

“Mom, you let him play football, oh my goodness he’s so little, I would never let my baby be out there,” people would say to O’Neal when seeing her son on the field.

“There is nothing I can do,” she’d respond.

Rodgers was 12 years old when his cousin was selected 16th overall by the Arizona Cardinals in the 2008 draft. He fantasized about being a cornerback in the NFL just like his big cousin, but because of his small frame, he was continually placed at wide receiver by his coaches.

After a season playing receiver at Middleton High School, Isaiah transferred to Blake High School at the end of his freshman year. When Isaiah told the coaches at Blake that he played cornerback at summer training camp, the head coach at the time informed him that he was too small and would instead stay at wide receiver. But defensive backs coach Duane Thomas told Isaiah he’d get a shot to play cornerback, which eased his discontent.

On June 8 of that summer, Rodgers was at a friend’s house playing basketball when his father texted him to say that he was on the way to pick him up, but Isaiah responded telling his father he wanted to keep playing. Craig was okay with that and gave him the time he needed to finish up playing with his friends.

During that time, waiting for his son, Craig Rodgers was shot and killed by the police.

Because rain started to pour down, Isaiah decided to run home, where he got a call from O’Neal telling him the news.

As any 16-year-old would be, Rodgers was crushed. The kid who was once known as joking and outgoing grieved his father’s death in silence.

“People that knew him knew that this was not really Isaiah,” O’Neal said.

Because he was the one who had texted his father telling him to wait, Rodgers put all of the blame on himself, thinking that if he had just told his dad to pick him up when they planned, then he’d still be alive.

When it came time for sophomore year in the fall, the death of his father still loomed over him, causing his grades to take a big hit.

“I literally didn’t do any work at all,” Rodgers said. “That set me back, and I had to make up a lot of courses.”

Thomas was the coach who handled the grades of everyone on the football team at Blake as well. They were able to build off of this relationship and grow a bond that Isaiah didn’t have with any other man at the time.

“He wouldn’t go to his uncle’s, he wouldn’t go to [Rodgers-Cromartie], he would go to coach Thomas,” O’Neal said. “Coach Thomas just knew how to handle him, he knew how to respond to him, and that day when I noticed he opened up to coach Thomas, that’s when I knew they had a connection, that he was his go-to guy.”

That day came one morning during Rodgers’ sophomore year. O’Neal was trying to get him to get ready to go to school, but he couldn’t stop crying. Knowing that something was wrong, Thomas had him come over and skip the day of school, telling Isaiah he could just do homework at his house.

Although Thomas expected Rodgers to be sadder than usual, he did not expect to see a completely broken-down Rodgers when he opened his front door. Thomas sat him down inside while wiping away the tears from his eyes and talked it through with him, sharing some of his own experiences.

“I had never seen him like that before,” Thomas said.

Thomas was late for work, but he didn’t care too much, knowing that there was a more important matter at hand. Rodgers stayed at his house all day doing homework and crying.

“That was definitely the turning point in our friendship,” Rodgers said. “We’re like best friends now.”

The coaches told Rodgers that he would be on JV when he started at Blake his sophomore year, because he was only 5-foot-3, 120 pounds at the time and the coaches just thought he was too small. But he had other plans and told them that he was going to be a varsity player for them right away.

Rodgers did end up making varsity, but was buried in the wide receiver depth chart. Thomas pulled him over to cornerback, where he started immediately. Rodgers was able to prove Thomas right, showing that his size was not much of a factor as a sophomore, as he was able to hold his own against kids that were double his weight.

“Even though he’s small, he uses his brain a lot to understand what’s going on,” Thomas said. “He always just jumped plays and would make plays that you didn’t think he could make with his size, but he used his intelligence.”

Rodgers had also developed a new pre-game ritual before each game. He would go to the endzone to pray before joining the team for kickoff, pointing to the sky after his prayer.

Heading into junior year, Rodgers was 5-foot-6, 130 pounds. Even though he was still one of the smaller players on the team and didn’t have a big growth spurt, everyone noticed a drastic uptick in his athleticism from the year prior.

By the end of his junior season, Rodgers was known as one of Hillsborough County’s best, making the county’s all-star game while starring at cornerback, receiver and as a return man. Rodgers was at a point where people would come up to him at stores and recognize him as No. 9 from Blake, which surprised him since Blake is not a well-known high school.

“I took it as practice to get ready for the future,” Rodgers said. “To take this moment now and pretend like you’re in the NFL or college.”

Rodgers-Cromartie took note of the big improvements his little cousin had made, changing the way he would talk to him, setting higher standards for him knowing that he had a real shot of making it to the NFL.

“For being in it so long and starting to have coaches ask you about [Rodgers], always wanting to know his size and his speed,” Rodgers-Cromartie said. “I tell him this is going to be a reality one day, so you have to train with that mentality.”

Rodgers was listed as a two-star athlete, which had colleges such as Oregon State, Eastern Michigan and Buffalo looking into recruiting him. But big-time schools stayed away. His small frame of 5’9” and 140 pounds was not appealing, regardless of his play on the field. Even worse, teams couldn’t be sure if Isaiah would be eligible to play. His grades were so poor that if they didn’t get better by the end of his senior year, he would not be playing football the next year in college.

The combination of those two things were very unattractive to big teams. Virginia recruited him early on, but eventually dropped out after a month or so because of his size, only looking for cornerbacks that were 6 feet or taller.

Another school that was looking into him was Tennessee State, where Rodgers-Cromartie played. They even offered Isaiah his cousin’s number, but that’s when Isaiah knew he had to do something about it.

Isaiah wouldn’t even give them a home visit, which surprised many outsiders, but was no surprise to his family, Thomas and his then-girlfriend, Gabby Beauchesne.

“He doesn’t want to be [Rodgers-Cromartie’s] cousin; he wants to be Isaiah Rodgers,” Beauchesne said. “Even though he inspires him, he still wants to be his own person.”

Trying to seize on the opportunity of Rodgers’ struggling grades, UMass recruiting coordinator Charles Walker found him, and soon enough he and cornerback coach Steve Costello were on a plane to visit Rodgers and his mother at their home.

Walker and Costello stood out to Rodgers and his mother. The two of them stayed for a few hours more than they were supposed to, talking about more than just football, discussing life and what UMass is like from a college perspective.

“They made my son feel comfortable without even knowing him,” O’Neal said.

The family-like feeling on top of the coaching staff at UMass passionately recruiting Rodgers led to him making a commitment shortly after the home visit. Rodgers felt UMass was home before even stepping foot on campus.

“We didn’t have an Isaiah Rodgers in the program,” Costello said. “Had Isaiah had academics, if his stuff wasn’t borderline, we wouldn’t have been able to touch him. It was a blessing for us because that helped us land him.”

After a strength and conditioning program that Thomas put Rodgers through his senior year, he was even faster and more athletic than what the UMass coaches had seen the previous year, and everyone in Tampa knew he was the man on the Blake high school football team. Rodgers rarely left the field, becoming his team’s top threat in all three phases of the game.

“Everybody respected him because even with all the attention he would get he would never put that in their faces,” Thomas said. “He was always putting himself at an equal level with everybody else.”

Later in his senior year, Rodgers put out a Hudl tape of his highlights for football, which caught the eye of Virginia, who wanted back in on the Isaiah Rodgers sweepstakes. Rodgers would’ve loved to play there when they first recruited him, but also resented the fact that they weren’t committed to him like UMass was.

“I shut that all down,” Isaiah said. “There’s no chance I’ll go there. There’s no point in them even trying.”

As a result of Isaiah’s bond with Thomas, he also grew close with his son, Donte Glover. Thomas’ house was Isaiah’s second home, meaning him and Glover spent a lot of time together, even to the point where they would have the same routine late at night.

Thomas would occasionally wake up around three or four in the morning to find Isaiah and Glover spray painting the grass to do footwork drills.

Isaiah and Glover would finish practice, Thomas would make them do homework each night from 7 to 9 p.m., and the two would immediately fall asleep and wake up around 2 a.m., something that would happen consistently throughout high school.

“We couldn’t sleep, so there was no point of just sitting inside,” Isaiah said. “We’d go outside and start doing cone drills and latter drills until it was time to go to school.”

Glover reaped the benefits from being around Isaiah so often in high school, keeping him away from the bad influences that Rodgers refused to allow in his life.

“I always tell my son, hanging around Isaiah is what got him to college,” Thomas said.

When prom came around later that year, Isaiah was crowned king. His popularity had reached an all-time high after his most recent football season, but when people went out to party after the event, Isaiah stayed home.

“[After his father’s death], he didn’t turn in a different way that he could have,” O’Neal said. “He didn’t go astray to what he set his goals to be. He went forth with it and I’m so grateful because it shows, and it shows to other people. Proud is an understatement.”

Rodgers had just barely made his grades good enough to be eligible to play college football, meaning he was able to head up to Amherst the summer following his senior year. When Rodgers stepped on campus, he was 5-foot-9 and 142 pounds.

Doubts started to creep in after camp in the summer, when Rodgers had the most interceptions of any cornerback on the team but came out listed as the last cornerback on the depth chart.

Costello could tell he was annoyed, but he knew that it was the only thing he could do. He knew Rodgers was already the most talented cornerback that UMass had, but he might’ve lost the cornerback room if he had a 142-pound freshman as a starter after only one camp.

“He was a no-brainer from the day he stepped on campus,” Costello said. “But you want people to earn things, you don’t want to give him the keys to the car on the first day when you’ve got other people that have been there before.”

Costello even vouched for Rodgers to start his first college game at the Southeastern Conference powerhouse in Florida. Head coach Mark Whipple voted against it, citing Rodgers’ lack of size and experience as the reasons to not start him. Rodgers wasn’t deterred, and would progressively prove himself throughout his freshman season, eventually earning the starting spot and never looking back.

At the same time, school was taking a toll on him. In high school he never cared much about grades, so it wasn’t something that was on his mind. It had to be when he was at Amherst, and he made it a priority for himself to not let his grades get to where they were in high school.

Rodgers would call his mother late at night saying that he didn’t think he could do it and that he might want to give it up or go somewhere else. O’Neal would ease him by telling him to sleep on it and to remember why he came to UMass in the first place.

When Rodgers and Costello prepared for the Mississippi State game his sophomore season, they watched more film than usual, knowing how big a game it was. Rodgers lost sleep to make sure he proved that they could compete with the bigger school, who was ranked No. 21 in the nation at the time they played.

Rodgers and Costello were able to get together and pick up on some of the Bulldogs tendencies that week watching film, which led to the game that completely switched Isaiah’s perspective. Isaiah had two interceptions in that game, one of which was returned for a touchdown.

“That really changed my entire career,” Isaiah said. “That was the main week where I actually watched film like a pro athlete. That’s where I started the trend of watching the games right after [they were finished].”

Mississippi State head coach at the time Dan Mullen ran into Isaiah after the game, telling him how great of a player he was, which was something that Isaiah was commonly getting from opposing college teams at that point.

“I just used it as motivation,” Rodgers said. “Just knowing that I do have the potential to play at those schools.”

Rodgers would watch film on weekends while friends were out partying, studying all sides of the ball. Defensive teammates would even ask him for advice from time to time, knowing that Rodgers had watched every second of each game.

“That’s my brother,” Tyshaun Ingram, Rodgers’ teammate and close friend said. “I know I can go to him for anything. My college experience would not have been the same without him. I don’t think I would’ve seen as much progress in myself.”

As his rise continued, Rodgers also started to realize that he didn’t have as much time to dwell on his father if he wanted to be a football player at the next level.

“It was another stage of, I’m not really just living for myself anymore, I’m living for him,” Rodgers said. “Life’s just too short to be sitting around, moping and crying when there’s people going through the same thing as me and still moving forward.”

“He’s always been good at putting all of his emotions towards football,” Beauchesne said. “He never let it keep him down. It’s always been anger and hurt that’s driven in a positive way.”

After many years as a losing program, UMass head coach Mark Whipple and his entire staff were fired, including Costello, at the end of Isaiah’s junior year. These departures hurt Rodgers, as Costello was a coach that he could go to for anything, a bond he didn’t hold with many people.

Rodgers mulled a transfer but decided on staying because he wouldn’t be eligible the following season, again remembering why he committed to UMass in the first place.

“Just knowing that I came here for a reason,” Rodgers said. “I wanted to change UMass and regardless of who the coach is, just finish out here and leave my legacy.”

Walt Bell and a brand-new coaching staff were hired, which meant growing pains for UMass. The roster thinned out after the coaching staff change, leading Rodgers to play almost every single snap on defense and special teams, becoming as indispensable in Amherst as he was at Blake High.

“I thought he did a great job of shouldering the physical leadership of not coming off of the field on defense,” Bell said. “Being a great kick and punt returner and practicing a certain way.”

With nine freshman starters on defense alongside Rodgers, it was obvious from the beginning that wins wouldn’t come often. UMass was one of the worst college football teams in the country last season, finishing with a 1-11 record.

“What I appreciate most as a coach, [going] through an incredibly difficult transition and difficult season, he was positive through the whole thing,” Bell said. “Not getting a lot of positive affirmation from the hard work you’re putting in, in terms of wins and losses and being positive throughout the whole thing.

The NFL is the main focus on Rodgers’ mind, but his future aspirations do not stop there, as he plans to help children of single parents get to college.

“He’s good with kids,” Beauchesne said. “Most guys, especially younger being left with a little girl or little boy, would just be nervous.”

“I know how hard it is for single parents to deal with,” Rodgers said. “I want to help those children with grades, football and to be able to make ends meet.”

Things didn’t get easier for Rodgers when it came to football, who wasn’t invited to the NFL Draft combine in February, which he took as another slight, observing corners who were invited that he knew did not deserve to be there over him and using it as fuel to outwork those who were invited.

Rodgers was able to catch the eye of many NFL teams during his pro day, running a 4.28 40-yard dash, along with a 40-inch vertical and a three-cone drill that all would have been ranked in the top three of all defensive backs in the combine.

Isaiah has been spending his time before the draft training with Rodgers-Cromartie, who also ran a 4.28 40-yard dash coming out of college. The two have spent a lot of time over the years together in their offseason, even racing once a year for bragging rights, a race that Isaiah has not lost since his freshman year of college.

The two have spent almost every day of this offseason working together, working on footwork, reaction skills, film and strength.

“Sometimes I look at my phone and I know it’s him and I’m like, ‘time to go to work’,” Rodgers-Cromartie said. “He keeps me young, he’s always willing to go out there and never gets tired.”

A 12-year veteran and a two-time Pro Bowler in the NFL, Rodgers-Cromartie knows what it takes to make it to the next level and feels confident in his younger cousin.

“I don’t think the NFL scouts really put their eye on him,” Rodgers-Cromartie said. “The kid should be talked about way more, I’ve seen his ability, I’ve seen everybody else in the draft, and he’s right up there with all of them. The only thing is that he didn’t have that exposure every week.”

Most NFL teams seem to disregard speed and athleticism when looking at Rodgers, and instead get caught up in his slim 5-foot-10 170-pound frame, hesitant to think that it can hold up. Similar to himself, Rodgers-Cromartie knows that his cousin is more than just an athletic body.

“If you can get your head around and find that ball, that puts you in the top tier right away,” Rodgers-Cromartie says. “And he does that. He finds the ball; he has a knack for the ball.”

Drafted or not, Isaiah Rodgers plans to go into training camp with the same mentality that he’s had since he’s been three years old.

All he wants is to get his shot to play with the big kids.

Joey Aliberti can be reached at [email protected] and on Twitter @JosephAliberti1.

Stephen Ridge • May 9, 2020 at 2:05 pm

I’m a UMass alum who has watched Isaiah Rodgers do remarkable things on the football field these last few years. He is fearless, ready and able to compete with the very best. My thoughts and prayers will be with him as he begins his first pro season. He has made, and I believe he will make, us all proud.

Isaiah Rodgers • Apr 23, 2020 at 1:26 pm

Thank you for the great story??

Libby • Apr 23, 2020 at 1:19 pm

NFL IS SLEEPING ON THIS YOUNG MAN NO MATTER THE SIZE HE IS CONSISTENT AND HE IS A BEAST..ALL HE NEED IS A OPPORTUNITY..I PROMISE WHO EVER PICK HIM UP..WANT BE DISAPPOINTED……ILL TAKE THAT TO THE BANK ..I PROMISE THERE WILL BE A WITHDRAW….

Eileen Meisner • Apr 23, 2020 at 1:08 pm

Great article Joe! Sports writing is your thing!

Enjoy!

Aunt eye

Elaine aliberti • Apr 23, 2020 at 1:08 pm

Great writing – I loved this article!

Almosse Titi • Apr 23, 2020 at 1:03 pm

Fighting adversity and always responding. Built for it❗️❗️❗️

Antonio Aliberti • Apr 23, 2020 at 11:30 am

Great story. I wish Isaiah good luck.