‘A lot of us grew up that day’: Reflections from Collegian staff who covered 9/11

As a national tragedy unfolded around them, a group of college kids running a student newspaper found a way to write about it

September 11, 2020

Part I: “The sky is just perfect”

It was a bright Tuesday morning in New York City.

In Lower Manhattan, bankers, construction workers, chefs, firefighters and police officers arrived for another day of work.

One hundred-forty miles to the northeast, it was also a bright Tuesday morning in Amherst. Professors, custodians, dining hall employees, administrators and advisors settled into their day at the University of Massachusetts. Students strolled through campus on the fifth school day of the year. On the sloped lawn surrounding the ripply, blue Campus Pond, they soaked in the morning sun.

At 8:46 a.m., it ceased to matter what the weather was like in Manhattan.

That story you know. Those of a certain age lived it. And those who were too young to remember may trace most major national events in their lives back to Sept. 11, 2001.

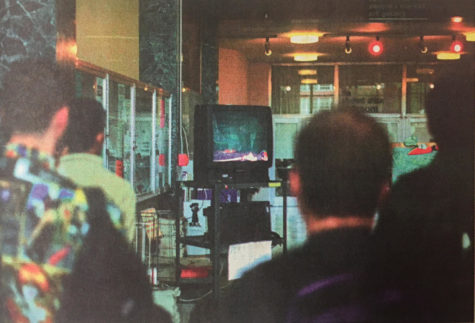

This is a different story, which took place a few hours northeast of Ground Zero. In the windowless basement of the UMass Campus Center, a group of college kids running a student newspaper watched the biggest event of their lives unfold on an old box TV. Then, as countless professional reporters did in Boston, New York, Washington, D.C. and everywhere else in the world that day, they found a way to write about it.

. . .

Sam Wilkinson, Collegian Managing Editor: I was living in Florence, which is out past Northampton, so I was driving to UMass every morning. I remember — it is burned in my brain — the brightest blue sky you have ever seen, just an incredibly beautiful morning.

Ken Campbell, Collegian Staff: You know what it’s like there in August and early September? It gets super muggy and it’s just god-awful. It’s like living in a dog’s mouth. And then all of a sudden it breaks, and it’s nice and cool, and the sky is just perfect.

Wilkinson: I always stopped by the Collegian before I went to classes. I walked into the office, and there were already people gathered around the old-school television we had in the office.

Campbell: We used AOL Instant Messenger a lot, that was the primary instant communication device. I woke up and went over to my desk, looked at the computer, and it was covered in new message windows. And the one on the very top was from Scott Eldridge, who at the time lived three floors above me. His message was just “turn on CNN.”

I turned on the TV and tuned to the news station. At the time they were saying “a plane has crashed into the World Trade Center tower.” They thought it was an accident. As I was watching, the second plane hit. You could tell it was no accident.

Jim Pignatiello, Assistant Sports Editor: I was probably up around 8:45 or so. I sat up and turned the TV on. There’s a shot of the Twin Towers and they said there was a plane crash. I think I assumed it was a small plane that messed up and that it was some kind of crazy accident. I called one of my roommates in and we watched. It was so weird. And then the second plane hit. I immediately said, “I need to get down to campus.”

Campbell: Something just clicked in my head. I turned back to my computer and I typed backed to Scott, “F****** bin Laden.”

Scott said, “What?”

I said, “He’s the only one with the money to pull this off.”

“What do we do?”

“Office.” I grabbed my jacket, which had my notepad and a bunch of pens in it, and I left.

Catherine Turner, News Editor: I woke up to the phone ringing. It was [my roommate and fellow Collegian staffer] Matt Sacco’s mom looking for him because she wanted him to know that his dad was OK — he had not gotten on the ferry [to Manhattan]. And I was like, “What are you talking about?”

She said, “Haven’t you heard the news? Turn it on!”

I walked into the living room and turned on the TV and saw the coverage and I was like, “Oh s***! I’m sorry, Mrs. Sacco, I have to go.” I just headed straight down to the newsroom.

Dan Lamothe, Assistant Op/Ed Editor and Columnist: I was in one of my first journalism classes that morning. It was a news writing class. Your basics, the inverted pyramid, that stuff. [Norman Sims, the professor], disappears to his office across the way for 15 minutes and comes back, and you can see the look of shock on his face.

He gave us a two-minute rundown on what he knew at that point, which was very minimal. And he says, “Why don’t you all feel free to finish your assignments and to do whatever you want as soon as you’ve done that.”

Wilkinson: I had a 9:30 or 9:45, maybe 10 a.m. class. The professor says, “Two planes just hit the World Trade Center” and a student says, “Oh my God, I can’t believe it. I hope everyone in Boston is safe.”

The professor says, “No, this is happening in New York City,” and the student says, “Oh, thank God.” Because at that time, nobody realized how serious the situation was. It was not immediately apparent. And the professor is like, “This is more serious than you think it is.”

Lamothe: Everybody finished their assignment, is my recollection, and I walked straight to the Collegian from there. Part of it, I think, was feeling compelled to participate in some way, and part of it was this fascination: How are we going to deal with this?

Part II: “Do you mind answering a few questions?”

The office of the Massachusetts Daily Collegian is a remote, two-room space tucked away in the basement of the school’s Campus Center. The dimly lit rooms have an open floor plan, filled with wooden desks and tables and couches much older than most of the paper’s current staff.

It’s the kind of spot that few people wander into unless they know how to find it. On nights where the staff is producing a paper, there are certain to be as many as two dozen people in the office working. On other nights, it’s more than likely that a few people are around doing homework, or at least pretending to.

For the paper’s staff, the space is a hub. For many, it’s akin to a second home on campus.

. . .

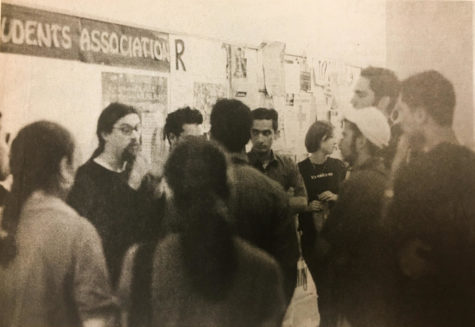

Scott Eldridge, Staff Photographer: Once I was in the Campus Center or the Student Union, I started to see more TV screens with the news on. By the time I got to the newsroom, it was clear that whatever was going on, we would try to document it. This was not news going on in Amherst, but it was news that was affecting Amherst.

So, it was sort of, how do you capture that idea or capture what was going on without being at the place where everything is happening. It’s sort of telling a story of people finding out about a story.

Wilkinson: The Collegian offices were sort of like an epicenter on campus for our staff. We had between maybe eight to 10 desktop computers, and we had an internet connection, so it wasn’t totally the dark ages. And then the TV was going nonstop.

Eldridge: Normally it had “Regis and Kelly” on in the morning. But it had the news on.

Wilkinson: That thing might have even had a turn dial. It was not a new TV, by any stretch of the imagination. That thing was old when we were there.

Turner: You’d get mesmerized. There were people who would just stand around it and stare. You couldn’t help but just get sucked into it. It was so surreal. You can’t really describe how surreal it was.

Wilkinson: People were coming into the offices and everybody was around one another. We decided pretty quickly — we’re going to continue to publish and tomorrow’s paper is going to be very different than what today’s newspaper was.

Lamothe: There was already a big group of staffers there. People were already working the phones. I remember cell phones were down, so it was a struggle to reach people in New York — it was a struggle to reach people who might have actually seen this. But I recall that there were enough people with connections in the region and in the city that we were actually working the phones, not unlike any other professional newspaper. Not to recast what we were seeing in other newspapers, but to actually do the work ourselves.

Wilkinson: At that point there was just this broad generation of stories. There was going to be hard news coverage, there was going to be what’s going on with the sports teams that aren’t traveling to their events, how is the university responding, how are students responding. Anybody that had an idea of what they could write about, it was, “Alright, well go write about it.” Get something done and get it back to us by five or six o’clock when we plan out how the newspaper is going to look.

I seem to remember us explicitly saying, “Hey, if you’re not up for working, no problem. But if you are, this is either what we want you to do, or we want you to tell us what you’re going to do.”

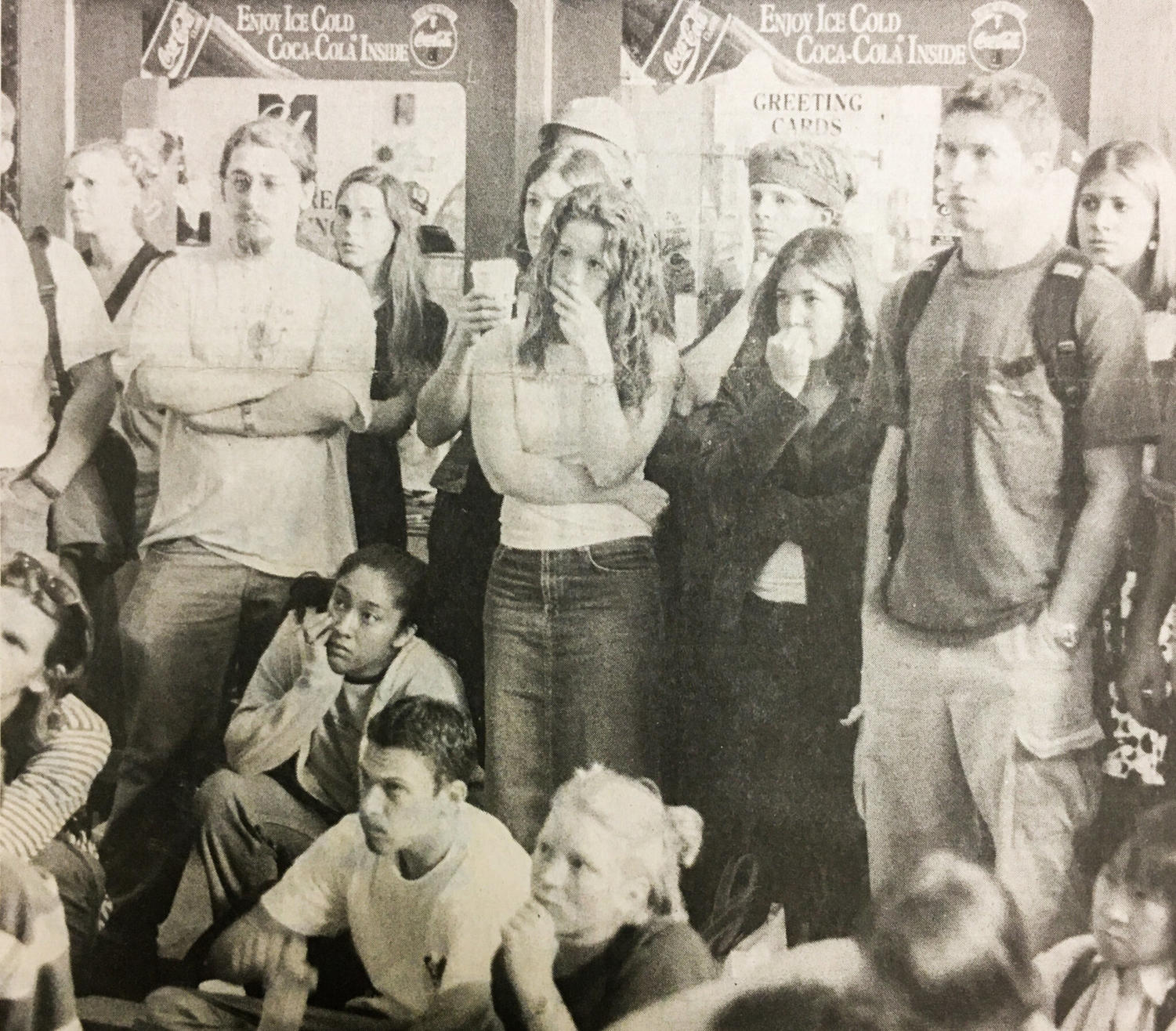

Campbell: They sent me out originally to get quotes. So I went to the bottom level of the Campus Center. There were TVs mounted up that would show cable and everyone was watching those. You’d go up and you’d start doing your thing — “Hi, I’m Ken Campbell, I’m with the Collegian. Do you mind answering a few questions?”

Wilkinson: I think we assumed, pretty safely, that absolutely nobody on Earth was going to be looking to the Collegian for national news. So, here’s this enormous thing that happened: What is going on in our local community, the community of UMass and the broader community of the Five Colleges? We left our focus there.

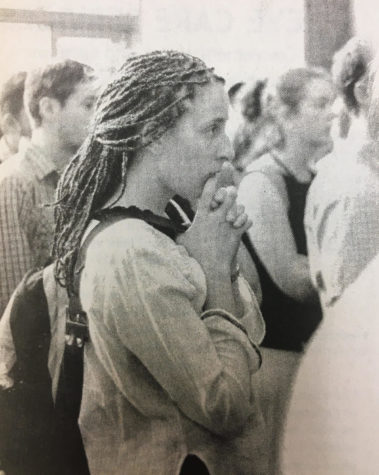

Eldridge: I forget if I was shooting with my Minolta 570 or if it was a Canon EOS 750. But it was film. I went to the Student Union because there were TVs in the lobby where people were watching. They had these expressions of trying to figure out what was going on and being shocked if they had started piecing things together.

Campbell: I was talking to a group of kids, got my quotes or whatever, and then went to the next group. I gave the spiel and then I said, “Do you mind telling me how you feel right now?” A kid looked at me and he had tears in his eyes, but he had this look of fury on his face. Just pure rage. He said, “I’m from New York City. How the f*** do you think I feel?”

And I said, “I’m sorry,” and I kind of backed away and started to take a step to the next cluster of kids. And I was just like, I can’t. I can’t do this.

Wilkinson: There was this mix of, we’re a team and these people are family and we want them to be OK, and we want good work out of them.

But also, for people who don’t feel like they’re capable of doing good work right now, we want to support them in whatever way we can. There was a lot of just faking our way through, in terms of saying, “These all seem like the best things we can possibly do to get coverage.”

Eldridge: I didn’t talk to people because at the time I was just, Take a picture, move, take a picture, move. I was documenting what was going on campus, or maybe that’s what I tell myself in hindsight. Because when I look back at some of those pictures, I do have some sort of split feelings about it.

Of course, I documented what happened that day, and I don’t think that’s a bad thing. But I also documented people’s vulnerabilities and that, in hindsight, I have a harder time being OK with. Also, maybe I didn’t talk to them because I was moving quickly. Maybe I didn’t talk to them because I didn’t know what I would ask or what I would say.

Wilkinson: It was fly-by-the-seat-of-our-pants-type stuff. None of us had ever dealt with anything like that, or covered anything like that, but it just seemed like it was the right way to be doing it.

Eldridge: I’d do things to check back in and to see if they needed me to go anywhere in particular. We would use the call boxes. The same ones that you could call campus police with, you could also dial any phone number on campus. So, I would just be calling the newsroom: “Do I need to go anywhere or just keep doing what I’m doing?”

Mike Delano, Arts Editor: They took me off the Arts and had me do this story talking to the Muslim Student Association. I remember meeting up with [Navid Khan] who was a leader of that organization.

. . .

Muslim students concerned about backlash; A community fears religious intolerance

By Michael Delano, Sept. 12, 2001

Times of tragedy fuel blind emotions. The need to channel one’s anger and confusion under distress often leads to irrational decisions in placing blame. People need an answer even when there isn’t one.

…

Navid Khan, president of the MSA, woke up yesterday morning “expecting to have a regular day” and was shocked when he learned of the attacks. He is discouraged, though, at the immediate reaction of some students.

“It is kind of sad that people automatically think of Muslims,” said Khan. “Our organization officially condemns the recent act of terrorism and all acts of terrorism, and grieves the loss of all human life.”

…

UMass student Jay Fitch spoke outside the MSA office yesterday afternoon to Muslim students, members of the MSA, and passing students about similar concerns for safety.

“Nerves are on edge, and people are going to act instinctually,” Fitch said. Himself a Muslim, Fitch stressed that “we must act with love.”

. . .

Wilkinson: In retrospect that was a complicated story, a huge story. It takes guts to walk into this room and say, “Hey, I’m not going to cover you unfairly,” especially given what happened. But Mike went out and did it.

Lamothe: I recall writing a column, and looking back on it, I think some of it was probably obvious. But I think some of it — it leaves me with a sick stomach knowing how much of it came to pass. Because I was warning about racial profiling and not blaming a group just based on whether you’re Muslim or something like that.

. . .

Dealing with the aftermath

By Dan Lamothe, Sept. 12, 2001

…It is OK for us to be angry. It is OK for us to be afraid. They are reasonable reactions; they just need to be harnessed. We cannot jump to conclusions and scapegoat groups such as the Islamic Nation for the tragedy, because we do not know the facts, details, and background information on all that has happened yet. Inflicting vigilante justice on innocent people while we are at a loss for what to do will only enhance the hatred that terrorism is about…

. . .

Lamothe: I finished that — knocked that out early. Not unlike a lot of days, the Op/Ed page is usually one of the first to go to the press.

I recall having lunch back at Franklin [Dining Commons]. I remember just the utter confusion. It was unclear whether or not there were other planes still in the air. It was unclear where those planes might go. At some point, the plane that went down in Pennsylvania became part of the puzzle. It just felt like there was a question mark about every plane left in the sky.

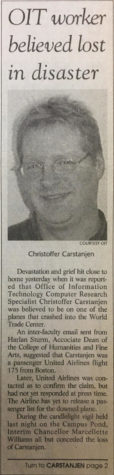

Campbell: The passenger lists got released and I remember people were going through it and seeing if they knew anybody. I remember there was one guy whose name was distinctive. Sure enough, another press release came out from the UMass News Office that he was an [Office of Information Technology] worker. He was going out to California and that was the flight he was on. We got that news alert and gave him a memorial box on the front page.

Lamothe: I went back at some point in the afternoon and they were so far along the way of what they were doing and it was so impressive watching them work. Virtually every desk seemed full, every phone was in somebody’s ear.

Pignatiello: It was the first time I’d ever had to work through something tragic. It showed the different mentality that we have to have in our field. Looking back at the paper and the performance of everyone, I think it’s so impressive to see the quality of the work. It’s a student newspaper, there’s no faculty advisor or anything. It was something to be really proud of.

We just worked the whole day. I don’t know if anyone even knew that classes were canceled. For someone who was very much a novice in journalism when I walked into the Collegian a year before and was now in my first week as an editor, it was a mega-download of education.

Wilkinson: I remember a lot of people who did not have a lot of experience writing about hard news going out and writing articles that were very different from what they were used to writing. On an incredibly bad day, the worst day nationally that any of us had ever experienced up until that point, everybody came together to do their very best work.

And I don’t mean writing stuff that they were the most proud of, but I mean getting focused on, here is what has happened and here is how “X” is responding to what has happened, whoever “X” is. We sent people out, they came back with really good work, we put it together and distributed it the next day.

Lamothe: I was new enough on staff that I didn’t have a full appreciation for how many irons they already had in the fire. I remember continually being surprised over the span of a couple hours at just what people were doing and able to pull off. When you talk to somebody who just gets off the phone and they’re like, “Yeah, I just talked to somebody who’s in Manhattan describing the scene.” It strikes me as, wow — it’s not something a college newspaper necessarily is expected to do.

Part III: Candlelight

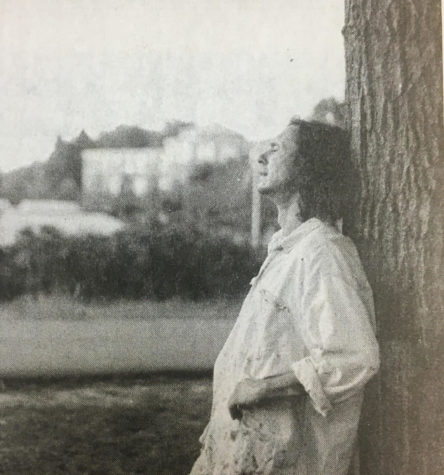

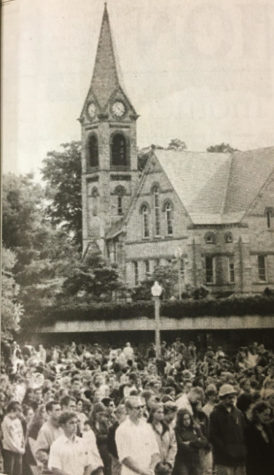

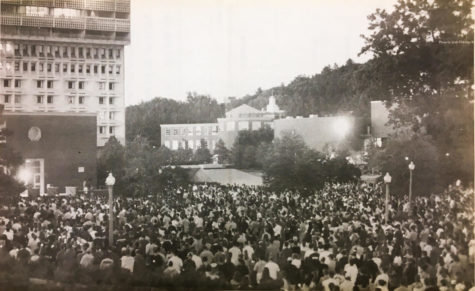

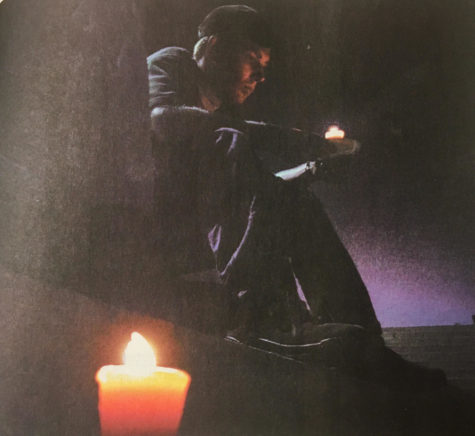

That evening, thousands of students and community members gathered by the Campus Pond for a candlelit vigil.

. . .

Turner: We left the basement and went out and looked at all the people gathering with the candles. I remember seeing people crying. There was a murmur but otherwise it was pretty quiet. I remember seeing the look of fear in people’s eyes. I remember the glow of the candles and how it reflected on the water. It encircled the pond and spread out up to the fence of the library and to the Old Chapel and back to the Fine Arts Center. But it was this feeling of, everybody’s here and we’re all here together. And this is the worst day in modern history since Pearl Harbor and we are living through it, together. We’re all in this weird moment, together.

Lamothe: I ended up covering the memorial service that evening. We had another writer that was primary, and I don’t even remember if I got a byline on the story. I interviewed a couple of students and was just pitching in however I could. It was a pretty striking memory, seeing all of those candles and how quickly that came together. Nothing planned, nothing organized and then a couple hours later you have all these students out there.

Wilkinson: In those days, the back page was generally sports. But for the back page of that newspaper, Scott Eldridge took a photo of the campus-wide gathering that night, which was thousands of people who came together and he got a wide shot of it.

As a photographer, he recognized what the right shot was going to be and I’m pretty sure he may have climbed in a tree to get it. That may be nostaligizing, but I feel 85 percent confident that was the story. That was the type of photographer and journalist that Scott was.

Eldridge: There was a light post — it wasn’t a tree, I’m almost positive of that — on the high bit near the library. We knew the time it was going to be. So, you kind of knew when people were going to start filtering in. There were thousands of people there. Part of how I ended up climbing a light post was I wanted to capture that scale. It wasn’t that high. I was probably standing on the base with my arm wrapped around the pole. I’m not that gymnastic, or whatever.

It is technical to some degree. And it’s super anxiety-inducing when you think, Boy, if I go back in and this is all screwed up, that’s going to be a problem. What if I loaded the film wrong because I was rushing? What if something doesn’t go right when I develop it?

Campbell: I remember Scott came back. He ran in with his negatives. What you would do was put them in these sleeves and then with a wax pencil you would circle the ones you want. Then you’d take those into Graphics and they’d scan them. He was using his lens as a magnifier, so he snapped it off his camera and he was looking through it. That was how you’d be able to get an idea of what shots were good.

I was like, “Hey, can I see them?” He showed me some of the shots he took and one of them was the one that ends up in the paper. The one everyone knows. I said, “How did you get that?” and he said he climbed up a light pole. He literally climbed up a light pole to take this photo.

Wilkinson: It was an incredible photograph. I think it’s probably the most memorable thing from the paper, to me. That’s what sticks out in my mind more than anything else. It illustrates as much as anything what the response was, because it’s not like there was much that people could do. You could go donate blood, you go make sure your family was OK but in terms of doing something meaningful, being together with your broader community was it.

Part IV: Now what?

Campbell: It was weird. One day you go to bed and you wake up and you’re in the middle of a war movie. Or a disaster film.

Turner: You watch “Independence Day” and see this fictional depiction of what it would be like if aliens really came to the planet and the havoc that it would wreak. It’s exciting and then Will Smith comes to the rescue. This had all of that trepidation and fear and like, Holy s***, what’s going to happen next? We’d never experienced anything like this before. But there was no Will Smith. You know? There’s just war after that.

Campbell: I remember not leaving the office much for several days. If I did leave it was basically just to go home, shower, change, maybe get something to eat and go back. Even if I wasn’t working on a story, that’s where I felt safe. Physically, you know, it’s underground. You can’t get much safer at UMass than you can in that building. But also, I knew everybody. Everyone’s a safe person. People would be like, “What are you working on?” and I’d say, “Nothing.” I was just there.

Lamothe: I remember [the office] being a much more impressive place to me afterward. Just having a better appreciation for how much people cared about their jobs. Just feeling like the place was something to be proud of and feeling like it was something I wanted to be a part of.

Pignatiello: I think the Sept. 13 paper is something almost to be as proud of as the Sept. 12 paper. It’s about putting in time and then coming back and putting out another paper the next day. That’s the thing about the Daily Collegian — there’s always another one. If you didn’t have a great paper, you can always say there’s another one the next day. But if you do have a great one, then you have to follow it.

Turner: As the fall went on, the sting subdued a little bit, but there was still this kind of ambiance of fear all the time. They could get us anywhere, if they got us there.

Campbell: There was a huge worry about Islamophobia. As much as I knew about al-Qaeda, I knew that it wasn’t Islam, it was madness.

There was a liquor store in Northampton. I remember that the owner was a Sikh, a traditional Sikh. He wore the turban and had a beard and everything. Super friendly guy. But I remember when you walked in, he had a big cardboard sign with American flags on it that said, “I am a Sikh, not a Muslim.” And I thought, Oof, he’s got to say that. Sure enough, I think at some point there was a Sikh man who was badly attacked. That was in the news.

Eldridge: The Muslim Student Association was concerned about what their experience was going to be as a result of this. And the months after proved that to be a reasonable reaction. You would get people yelling at Student Association tables or protests and people would happily yell at them, accuse them of being terrorists or link them to Sept. 11, which was BS, but nevertheless happened then and happens now. So, you could see that sort of fear, and maybe in hindsight you could see in their faces that they already knew what was coming down the road.

Wilkinson: Even in that day and the days that followed there were hints of the societal cracks that were going to be worsened. Even though UMass is a pretty liberal, pretty tolerant place, you had the creeping incriminations that began of These people are guilty or Those people are guilty and then the response from people who were obviously not guilty of “No, I’m not.”

Lamothe: That spring semester, I got asked to cover an Alumni Association trip down to Ground Zero with Scott Eldridge. I had never been to New York City, I had never really been out of New England at that point.

I ended up doing it as a first-person piece and just feeling like this is such a serious story to be writing at a relatively inexperienced age. What did it for me was seeing the cards and the letters stapled, tacked and taped to various shrines that were in the area of Ground Zero and knowing that there was a family attached to every single one of these things. I think a lot of us grew up that day, that week, that month. I’m 38 now, I was 19 or 20 at the time. It’s a half-a-lifetime ago, but it sticks with you so much.

. . .

Odyssey honoring the lost: Alumni Association makes trek to Ground Zero

By Dan Lamothe, April 10, 2002

…We started to read the names off, one by one. After each name was read, the folder with UMass letterhead inside emblazoned with the names of the victims got passed on to the next member of our travel group. My mind drifted as the names were read. “Christoffer M. Carstanjen… Geoffrey W. Cloud… Tara Shea Creamer… Peter Hashem… Todd Russell Hill… John C. Jenkins… Thomas N. Pecorelli… David Ellis Rivers… Sheryl L. Rosner Rosenbaum…”

At this, the letterhead was sitting in my hands. “Jessica Sachs,” I said in a clear voice. My voice caught, though, as I saw that Sachs was a member of the Class of 2001. I later confirmed that she indeed graduated last spring. Graduated in spring. Died in the fall. She was 22 years old.

The last person in our group named one other victim the Association had chosen to recognize: Peter J. Ganci, chief of the New York City Fire Department. His daughter Danielle is a member of the UMass Class of 2000.

…

My eyes fixed on individual letters, and my heart sunk. Each letter, while all nearly the same, told the story of another individual that was a victim of circumstance; thousands of individuals, thousands of different stories, one act of hate.

…

Finally I stopped, perhaps finding what I was looking for. In a childish crayon-drawn scrawl, I read the following: “Dear Tommy Cahill, I miss you a lot! I wish you could come back I love you so much!!! I wish you could come back and swim in the pool. You were so fun to play with!!! You were a grate uncle. I used to have four uncles but now I have three uncles with one in heaven. …from Ashley.” A heart was drawn in purple after the word heaven.

My heart broke. My heart will break again every time I think of that letter. As I came back to reality, I realized several men in kilts with bagpipes were playing “Amazing Grace.” I had not even seen them come in. The steady whir of the cement mixer pouring a new sidewalk hummed in the background of the bagpipe music. The wind came up again, and I shivered. Two tears dropped from my left eye. Perhaps the wind blowing the dust into my face had caused them; but I don’t think that was it.

———

Quotes were lightly edited for length and clarity.

Will Katcher can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter at @will_katcher.

Paige Giannetti • Sep 13, 2020 at 12:07 am

This was a great article to describe what many went through at that time–including the journalists!

Theresa Dooley • Sep 12, 2020 at 10:11 pm

Well done.

Laksh Arora • Sep 12, 2020 at 7:05 pm

Fabulous! I don’t want to be contacted so I haven’t put my actual contact information but this is a brilliant read, Will! A big pat on the back to you. It really shows how affected everyone was by the horrible incidents that took place that day. The way you tracked all these people down and got such meaningful quotes from them is truly remarkable! Very impressed with your work and The Collegian as a whole. Good job everyone!