How Black-led student groups are creating and maintaining spaces for long-lasting community

Members and leaders of Black-led student organizations share their reflections on the past and aspirations for the future for their groups

February 28, 2021

When Chinedum Eluwa first arrived at the University of Massachusetts as a Ph.D. candidate, he didn’t really care if he met other African graduate students. His primary focus was his studies.

“This was the second time I was moving far away from home, changing my friends, and I was like, ‘Oh, my goodness, I’m going to start again!’” He laughed. “And I was like, okay, no, I’m just going to go to work and go back home.”

Eluwa had become accustomed to moving. He had gone to the United Kingdom from Nigeria for graduate school, followed by the move to the United States in 2016 to continue his studies.

After a few chance encounters with some of its members and a gratifying first meeting, Eluwa found himself joining the African Graduates’ and Scholars’ Association, a graduate student organization on campus.

Three years later, he was a dedicated member of the group’s executive board.

Eluwa came to view the group as family, made most apparent when he officiated a wedding between two members of the association in 2019. The couple had reached out to Eluwa as they did not have family members in the United States to fill that role.

Student organizations at UMass have long been creating and maintaining spaces for Black students to collaborate, connect and build community. But these organizations would not exist without the dedicated efforts of pioneering Black students who noticed a lack of spaces where they could practice their culture and celebrate their identity.

Gorana Gonzalez, a second-year graduate student in the development science program, explained that surrounding herself with Black peers provides her with “balance.” To do so, she has been helping with facilitating “Black graduate student community” in her college through monthly meetings designed to provide a space for “talking and connecting” among Black graduate students, faculty and the College of Natural Sciences.

“I thought this is a great way for me to . . . get involved and do something that I feel would really immediately benefit Black students on campus,” she said. “We’re managing to find space, and I think that’s what’s important.”

Gonzalez acknowledged the difficulty in fostering Black community at a predominantly white university. “Despite the fact that there might not be a lot of Black students on campus I’m really, really happy to be in a position and space where I am able to connect with the Black graduate students and the Black faculty,” she said. “I feel it definitely has been my saving grace.”

The UMass chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People came about to designate a space for similar reasons. Students at the University noted that while its library was named after one of the NAACP founders, W. E. B. Du Bois, there was no existing chapter of the nationwide organization on campus.

Motivated by the various incidents of racial harassment on campus in 2018, including racial slurs being written on a dorm bathroom, the founding students got to work.

Nearly a year after they had been active on campus, members of the UMass NAACP gathered on a late night in Chicken & Co., an on-campus restaurant, to draft their proposal to the Student Government Association for official Registered Student Organization distinction. Their first two submissions were rejected for a few errors in their proposal, but after filing an appeal, they officially became an RSO.

The sense of community and space that the NAACP provides Black students on campus, however, did not need RSO status to be apparent. Like so many other Black student-run organizations on campus, the UMass NAACP provided their peers, who often felt confused and left out following their arrival to campus, a place of comfort.

Fabiellie Mendoza, the president of the UMass chapter of the NAACP and a senior pursuing a dual degree in political science and philosophy, described the alienating experience that some Black students experience when arriving at a predominantly white institution like UMass with minimal representation and guidance.

“I feel like one of the biggest obstacles is that you don’t really feel like you have a community when you first get in… It just made me kind of shrink into myself until I started to meet Black kids. And I was like, well, there’s a whole other community….Like all the people of color all together, just vibing, giving each other advice,” Mendoza said. “I feel like that’s the reason I’m . . . successful and able to do so many things at UMass.”

Philip Derisse, co-president and co-founder of the UMass Brotherly Union, echoed the sentiment that coming to a PWI can be a big change for students. “I feel like a lot of times you walk into certain rooms, and everybody expects you to act a certain way or talk a certain way,” he said. “Basically, you’re a representation of a whole race.”

For Sudzie Penn, the president of the Haitian American Students Association and a senior microbiology and biochemistry major with a Chinese minor, freshman year came with experiences of isolation. She expressed feeling out of place when she first arrived at the University, even “sad and depressed” at times.

“I remember that type of feeling my freshman year, like when I wasn’t involved in anything, and you’re trying to figure out who your friends are [and] what you want to do,” Penn said. “So, I definitely think these communities allow people who are already in a minority to feel more comfortable.”

Penn emphasized the role that HASA plays in giving Haitian students an opportunity to not only embrace their own culture and identity but also share it with the rest of the campus community.

“It just was created to allow our community to learn more about Haiti. From the foods to the music, our language . . . a place for people who are Hatian and wanted a community, but also people who just like, want to learn about Haitian culture,” she said.

For the UMass Brotherly Union, a similar sense of community within the organization is apparent. “With UBU, with all of us uniting, putting ourselves together, putting our minds together, our talents, our skills, everything combined, . . . we just feel like we’re some of the strongest people when put together,” Derisse said.

The Union came to be when Derisse, a junior public health major on the pre-dental track, and Edosa Osemwegie, co-president and co-founder of the Union, recognized the deficit in opportunities for Black men on campus to gather and connect. “I believe [that] if a door doesn’t exist, you create it,” Osemwegie, a senior legal studies major, said. “And that’s what me and [Derisse] . . . did with this organization.”

The group aims to provide members with valuable information, resources and connections to succeed at the University and beyond. “We wanted to host meetings that provided value to students,” Osemwegie explained. “You know, when you look at great businesses in the world, what differentiates them is value. So that’s what we wanted to add to our organization.”

He said that one of the things he loves the most “is that I’ve aligned myself with brothers that I know are capable of great things.”

Derisse expressed that to him, the most important aspects of the organization are the brotherhood, camaraderie and unity fostered between members. “Even though we’re the minority on campus, we put ourselves together, and we see all of ourselves in the same room,” he said. “It feels like we’re one of the biggest things here.”

Facilitating events & meetings

Through events, big and small, student organizations are able to connect with the greater UMass community and beyond. HASA, for instance, is known for annually hosting HASA CASA, an event hosted in collaboration with Latinos Unidos to showcase culture, history and heritage. It features traditional foods, dances and more from Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

HASA also hosts an annual charity date, which features dance team performances and an auctioning of dates to raise money for Haiti. This year was the first that the long-held tradition could not take place in-person; however, Penn was determined to keep it alive. With some alterations, the event occurred virtually on Feb. 25.

Throughout the largely virtual academic year, many organizations on campus have had to tackle the transition online, but some found their gatherings to be as important as ever during the pandemic.

Eluwa, now the president of the African Graduates’ and Scholars’ Association and a fifth-year Ph.D. candidate, said the virtual format of the fall semester took a toll on him personally. “Going remote made me actually feel more homesick than when we were in person,” he said.

When AGASA meetings went virtual, he noticed that attendance at weekly gatherings doubled. Before the pandemic, their weekly brown-bag talks typically garnered about 13 attendees, Eluwa said. Now, attendance ranges from 30 to 35 attendees.

The effects of the pandemic on virtual events and meetings can be described as “a double-edged sword,” said Brandon Barker, president of the Alpha Kappa chapter of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity and a senior dance and public policy/finance double major.

“When you see a Zoom event, you’re like, ‘Awesome, that looks really cool!’ . . . But then at the same time, you know, by the time you’ve had Zoom classes all day from nine to five, and then the event starts at six, you’re ‘Zoomed out,’” Barker explained.

Some of Barker’s favorite events that the Alpha Kappa chapter of the fraternity hosted before going virtual included a men’s’ talent show, a self-defense lesson for women and a candid discussion about Black love and relationships with the Sigma Gamma Rho sorority, which he described as a time that he “felt comfortable being vulnerable.”

The fraternity also hosts an “Alpha Week,” where each day has a different theme and corresponding event. This year, the series took place virtually, beginning on Feb. 22. The Alphas hosted different events every day of the week, including “Wellness Wednesday” and “Service Saturday.”

Barker said these events “look at different aspects of Black culture [and] Black living, relevant to today or . . . based in history.”

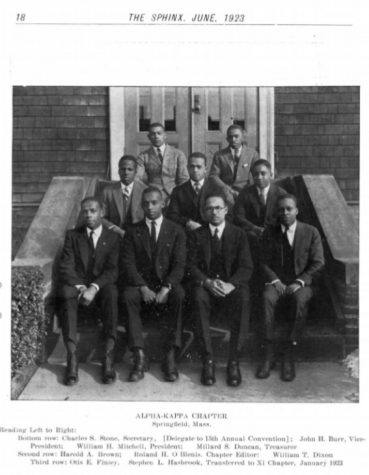

The Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity was founded in 1906 at Cornell University. Barker reflected on the difficulty of creating spaces for Black students in those times.

“We managed to do it back then and [created] a fraternity, right? And so if, if we did it back then, with those hardships and circumstances, we can certainly do it now,” he said.

Through digital initiatives, the UMass chapter of the NAACP also attempts to revitalize many of the popular events they hosted in person while simultaneously bringing life to new ones.

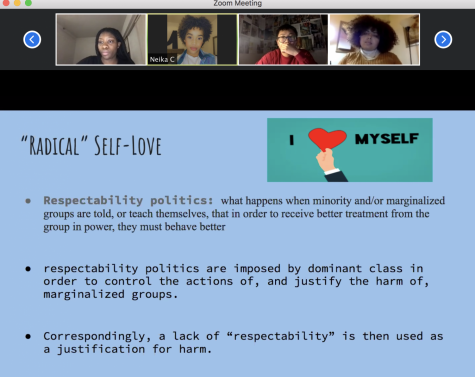

The organization recently hosted its annual NAACP week in a virtual format, which kicked off with a “Radical Self Love” event on Feb. 15. The event was driven by the “belief that your body, self, race are not things that need changing,” NAACP External Affairs Chair Danyella Mulunda, a senior political science major, explained.

The event featured a discussion on respectability politics — the idea that marginalized groups must behave better and conform to social norms in order to gain respect from the group in power — as something that damages the ability of many to love themselves entirely.

The NAACP also hosted a “Voting Tuesday” series during the fall semester, a multi-part series in conjunction with the UMass chapter of Leading Women of Tomorrow designed to educate others around the voting system and political issues at the forefront. Mendoza hopes future board members can continue this series past voting season.

When it comes to raising funds, student organizations often rely on their own efforts through various types of fundraisers. Mendoza pointed to the success of “Soul Fest,” hosted by the Black Mass Communication Project at UMass, to argue that Black-led student organizations should receive more acknowledgement and funding from the administration. The series of events typically takes place in April and draws students from across the Commonwealth.

“That’s money that UMass and Amherst profit from because they’re students from all over the state that come,” Mendoza said. “Like at some point, they told me that some students came from Florida to come to this party.”

Gonzalez also emphasized the fact that while she is thankful to have a sense of community within her college, it is “one little positive . . . in [the] grand scope.”

“There’s still a lot of work and you can’t depend solely on students to fix it,” she said. “It’s wonderful that they’re active, but it’s in a larger system that should be there to support them.”

Impact of spaces for Black students: UMass and beyond

The impact of spaces designed by and for Black students does not end with graduation. For Eluwa, the connections he made throughout his time with the African Graduates’ and Scholars’ Association remained strong even after his peers graduated and returned to their home countries.

“Never before in my life did I pick up a phone and call someone in Kenya, you know? I mean, the only international calls I was making was to Nigeria. Now I call people in Kenya and Ghana, like, oh my goodness,” Eluwa said. “You never know what the community you find yourself in will do for you.”

The long-lasting bonds between students are fostered in every aspect of the association. “We’ve sort of been able to build this, like, strong family, a network of people who are willing to help each other . . . and support each other,” he said. “Each time, we have meetings, the joy and the laughter is incredible.”

Making the decision to join a student group can be life changing. Before Barker even first pursued his fraternity, he immediately knew it was a circle of people that he wanted to associate with.

“I’m going to, you know, these marches, these rallies, I’m . . . signing different papers, and I’m doing a lot of advocacy. And I’m seeing the same people there who are Alphas, and I thought to myself, ‘Okay, this isn’t a coincidence,’” he said. “These are people who are at the forefront of everything that’s leading to systemic and concrete change on campus.”

Barker knows that the people he has met within the fraternity are people who will be with him long after he crosses the stage for his diploma.

“It is a long-term time commitment of brotherhood and friendship, something that I’m going to take with me after college . . . you always have that network to lean on and to bounce ideas off of, [or] do community service with.”

Although these student groups have persisted remotely for the past year, the ultimate goal is to return to occupying the same spaces physically. With a hope to return to campus, many organizations have in-person events and ideas in the works.

“People at UMass like to go to events,” Mendoza said. With that idea in mind, one of her aspirations was to host a dress-up gala with a showcase for Black art.

The founders of the UMass Brotherly Union also have big aspirations for the group, including providing scholarships, mentorships, and hosting large events and concerts in the future.

“Hopefully, UBU is something that is around when I have my kids 20 years from now,” Derisse said.

Sara Abdelouahed can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @AbdelouahedSara.

Saliha Bayrak can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @salihabayrak_.