Writers from Nummo News, UMass Amherst Black Alumni Network Facebook page

Looking back on the history of Black presence at UMass

A Black Presence Initiative was launched to further explore and document the experiences of Black students at UMass

February 28, 2021

In the University of Massachusetts’ 157-year history, Black students have only been present in larger numbers for 53 years — meaning 100 years passed with close to no Black representation on campus.

Today, Black students still remain underrepresented on campus, accounting for five percent of the undergraduate population. For the fall of 2020, only 17 percent of the University’s population came from underrepresented backgrounds.

In this sense, UMass has always been and remains a predominantly white institution (PWI).

This is a short history of Black presence on the UMass Amherst campus.

According to the University archives, Massachusetts Agricultural College (UMass’ former name), was predominately male and from Massachusetts up until the early 1900s.

Though there was little racial and gender diversity, the archives note that there were neither “any formal policies barring the admission of women or people of color” at the time.

During this period at the turn of the twentieth century, the archives report that the campus community was frequently rattled with debate over civil liberties. Some students in 1901 traveled to hear Booker T. Washington speak in Northampton on “The colored race and its relation to the productive industries of the country.” The College Signal had reported that “All seemed well and pleased with the lecture.”

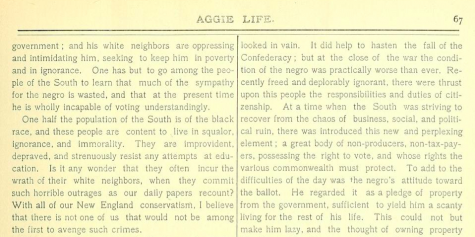

On the other hand, writers at Aggie Life, the student newspaper which preceded the Signal, published racist ideas, and wrote that Black people were “content to live in squalor, ignorance, and immorality” and “improvident, depraved, and strenuously resist any attempts at education.”

This was the divided campus environment when the first Black student arrived on campus at MAC in 1897 – George Ruffin Bridgeforth.

Bridgeforth was born in Athens, Georgia. When he enrolled as a freshman at MAC, he was nearly 24 years old.

“As far as can be determined, African American students lived in the dorms and boarding houses side by side with their white classmates, one some occasions sharing quarters. As a group, these pioneering students participated fully in the life of the college – with the noteworthy exception of fraternities – and they made their mark in both athletics and academics,” according to University archives.

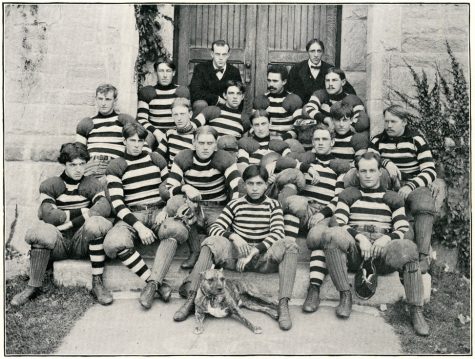

During his time at UMass, Bridgeforth was selected as the Sergeant at Arms for the sophomore class, on the rope pull team, a member of the College Shakespearean Club, played on the football team, made corporal in Co. A of the Cadet Battalion and was president of the YMCA. As a junior, he also won second prize in the Flint Oratorical competition.

After graduation, Bridgeforth pursued a career in education, landing his first job in the Agricultural Department at Tuskegee College. Also at Tuskegee at the time were Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver.

He later left Tuskegee and accepted a new position as President of the Kansas Industrial and Educational Institute in Topeka in May of 1918. During his time there, Bridgeforth worked to establish a hospital and nursing school.

The University archives state that, for the next decade after Bridgeforth’s arrival, about one more Black student came to MAC in each new class of 25-75 total students.

Other first students from the time include William Lane Hood ’03, William W. Peebles ‘03 and William H. Craighead, who is thought to be the first ever Black captain of a sports team at a PWI.

The archives list nine first Black students. Of their achievements, they write “six of the nine taught at an Historically Black College or University – two becoming presidents – and of the other three, one became a dental surgeon and another was a County Extension agent teaching African American farmers in Virginia.”

It is unclear who the first Black woman to attend UMass was.

It was not until almost 60 years later that Black students began increasing in enrollment.

In 1954, the Supreme Court delivered its landmark decision of Brown v. Board of Education Topkea, declaring racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. Though UMass already had no policies barring Black enrollment, this decision did spur the integration of the University.

According to a Status Report written by the Afro-American Studies department in 1980, when the 1954 decision was delivered, many white southern state universities tried to find ways around this ruling to continue to keep Black students out. One tactic they used was offering scholarships to Black students to instead attend universities in the north.

“Tuition and fees, living expenses and books — all paid to keep black residents out of Southern ‘white’ state schools,” according to the document.

UMass was one of the Universities where these scholarships were accepted. More than 10 years after Brown v. Board, however, Black students were still greatly underrepresented on campus. In 1965, the document states, about 50 out of the 18,000 students on campus were Black. Most of them were also graduate students.

According to the Fall 2010 edition of the UMass Magazine, in the 1960s, UMass had fewer Black students on campus than the universities in Mississippi or Alabama and had more students from Asia and Africa than Black students from Massachusetts.

The students who attended the University between 1960 and 1970 were dubbed the “Black Pioneers” by Cheryl Evans ’68. Evans undertook a project in 2018 to collect and document the stories of these students.

In her own interview, Evans recalled first arriving at UMass in 1964 for freshman orientation and not seeing any other Black student.

“It was like being transported to another planet,” she said in the interview.

Her entire freshman class only had 12 Black students, six men and six women, and she recalls feeling invisible to the rest of the University.

“I remember going to one of those freshman mixes, I think they called them, and standing there and people going by and dancing and I just felt, like, ‘this big.’ I realized the experience they’re having…I wasn’t included,” she said.

Evans also talked about not having places in town to get her hair done or be able to buy pantyhose or makeup for her skin color. She would have to take the bus back to her home in Medford to get her hair done properly.

After realizing this lack of Black representation on campus, Evans decided to organize some of the other Black students around 1965.

“I could have passed through here with no ripples at all, or, [said] ‘something has to change, I can’t leave this like this.’ And so that became I’ll call it, the ‘additional degree,’” she said.

During her time organizing at UMass, Evans gained the nickname “Little General” for her small statue but commanding nature.

A full video self-recorded by Evans reflecting on her time at UMass can be found here.

The Black organization first started as the ‘Carver Club,’ “because Carver was neutral enough to not scare anybody,” Evans said.

Later on, Evans was elected to the Student Government Association as a representative from Arnold House. After learning about the process of becoming a Registered Student Organization, she helped establish the Carver Club as the new “Student Afro-American Association,” the first Black student organization on campus and was elected its first president.

Evans remembers that around the years of 1966 and 1967, she and some members of the Association met with the Dean of Students at the time with a proposal to recruit more Black students.

“We didn’t ask for any money. We said we would do the recruiting,” she said.

The Dean replied saying that the administration would think about it.

Around the same time, five Black faculty members — Randolph W. “Bill” Bromery, Lawrence A. Johnston, William Julius Wilson, Edwin Driver and William Darity — began on an initiative to increase Black enrollment and support at UMass.

Reflecting on the period before the 1968 push for recruitment, the Status Report cites that “Almost any discussion of recruitment of Afro-American students, whether at meetings or parties, eventually led to the question of their qualifications for college work.” It continues, “We noted, also, that ‘lack of qualifications’ all too often implied the inability to learn rather than poor high school preparation for college. We recognize the latter as justification for concern but in no way as a reason for the University to avoid what was clearly its moral, if not necessarily legal, duty.”

For faculty members, it became clear that it was necessary to create a system to support prospective Black students’ needs.

“Those of us who had received our secondary schooling in the North knew how Black students were kept out of academic tracks, the courses they were discouraged from taking, the career counselors who attempted to lower Black pupils’ ambitions, even the teacher who literally wept before her class, apologizing for the Black youngster’s sitting before her and explaining that ‘Negroes simply can’t grasp the material, but state law requires me to teach them,’” wrote the faculty in the Status Report.

To address these needs, University faculty wrote a grant proposal for the creation of the Committee for the Collegiate Education of Black Students. CCEBS was meant to recruit and retain Black students and provide them with economic and academic assistance such as orientation, counseling and tutoring.

According to an article from the Journal of African American Studies, the Ford Foundation accepted the grant to underwrite the education of Black students at UMass and provided the program $1 million in the two year period between 1968 and 1969. Other funding came from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the U.S. Office of Education, the UMass Student Senate and UMass alumni.

After the creation of CCEBS, the Committee worked to increase the enrollment of Black students on campus, according to the UMass Magazine. In 1968, they presented the University with a list of 120 potential students to admit, of whom they hoped half would be accepted.

Initially, the University only wanted to accept two or three of the 120. Yet, the five professors on the Committee did not back down. They threatened to resign if the University did not meet their demands.

After this, the University agreed to accept all 121 students – 51 men and 70 women.

“The graduates from that first-year cohort would outnumber the full roster of Black graduates in the previous 105 years of the university’s history,” says the Magazine.

According to the Journal of African American Studies, with the help CCEBS, the enrollment of Black students then rose to around 500 by 1970.

One of the students from the 1968 CCEBS class was Anita Anderson, who was also interviewed as part of the Black Pioneers project.

Of her time at UMass, Anderson said that what most stands out to her was “the community that we built.” She said that she had study partners and it felt as though students were helping one another.

Anderson said that when she arrived on campus as a music major, she learned that she “wasn’t equipped for the difficulty of classical music.”

“I just was not disciplined at 17,” she said.

Before departing UMass in her sophomore year to pursue a singing career in Los Angeles, Anderson was a vocalist in a band on campus.

Of the environment between students on campus, she said “There was a lot of people judging each other by the color of their skin but I wasn’t into that…I’m not saying I never experienced prejudice because I did experience it, but that was a select few people – kids that were raised that way. I always believed you could teach hate, but if you don’t teach it you won’t have it.”

In 1971, Bromery became the first Black chancellor at UMass and was known as a “champion of diversity” who continued to push for the expansion of educational opportunities for Black students and also helped acquire the W.E.B. DuBois papers.

More oral histories and documents about the Black Pioneers can be found here.

Though the University administration was mainly open to the recruitment of Black students, the issue was met with some hostility from faculty and other students.

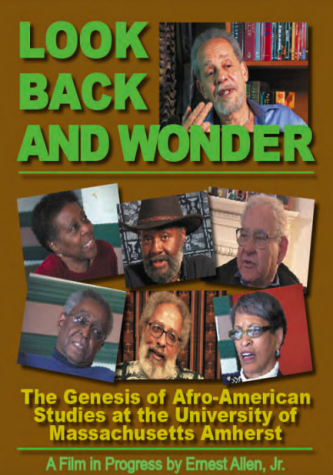

“The administration, they were much more progressive I think than the faculty,” recalled Professor Emeritus Ernie Allen, who joined the faculty at UMass in 1972.

As a faculty member during the time that this first wave of Black students was on campus, Allen remembers that Black students would sometime boycott classes after hearing professors make racist remarks about people of African descent.

Still, he acknowledges that there was “tremendous support” from some faculty and department, such as the English and history departments.

“There was also a fair amount of hostility, I think, on the part of the regular counselors, that sort of thing. They would sometimes advise Black, white students not to take African American studies courses, you know, because they would face a hostile environment,” added Allen.

Much of the student hostility towards Black students, the Status Report documents, came from “fraternity row.”

The document reports that one day in the spring of 1969, a group of fraternity boys chased several Black students to their dorm in Mills House, later renamed and transformed into the New Africa House.

“When the students secured themselves behind a locked door, the fraternity gang left, vowing to gather an even larger number and return to ‘do battle.’ Barricading themselves in the house, the Black students went through the halls knocking on doors, announcing that when the fraternity gang returned, the students housed in Mills were ‘either with them or against them’ and if they were not “with them” they should leave the dorm. It was easier to fight, they felt, if all their foes were in one place. Uninvolved white students left the building. Meanwhile, more Black students joined those in the house and what began as a defense tactic on the part of harassed Black students was blown into a full-fledged building take-over reminiscent of those taking place over the nation — demands and all,” documents the Status Report.

Audio news coverage of the takeover at Mills House can be found here.

Other attacks on Black students, Allen remembers, came during riots after the World Series.

Much like the traditions that remain today at UMass, whenever the Boston Red Sox won the World Series, students would erupt in riot to celebrate the victory. Allen said, however, that some of them would turn into anti-Black rallies.

“There was a lot of, if you will, racial hostility in the country and that’s something that was reflected on campus as well. And to a very large extent, only the bravest white students would show up to Black classes, you know classes where the majority of students in that particular class were would be African American,” added Allen.

He emphasized that there seemed to be fear towards the Black students on the part of white students.

Professor John Bracey, who came to UMass in 1973, recalls that in his classes students usually sat segregated from one another.

“Kids would tell me that their parents would want them to drop the class because they didn’t want an African American professor,” he recalls.

“The contrast that I guess I’m trying to make here is that, if there was a march on campus by Black students and that sort of thing, white students generally stayed away,” said Allen. “It’s very common today to have white students in large numbers join [protests]. That was not the case back in the 60s — there was a certain kind of fear of the New Africa house and what went on there.”

The Status Report also noted that there was an “overwhelming curiosity by the town and campus communities” of the new class of students in around 1968.

“All too often, they were made to feel they were experimental animals in a laboratory,” the professors wrote.

The press would pry into their lives to get information about their lives, adjustments, successes and failures. It is unclear how large a part Daily Collegian reporters played in this at the time.

As a response to the fact that Daily Collegian was also not writing about the needs and interest of Black students, Black students created their own newspaper in 1969, titled Nummo News.

According to the UMass Amherst Black Alumni Network Facebook page, “We focused on issues and stories that affected and were pertinent to students of color. We were committed to the newspaper because we felt that these issues and stories might not otherwise be covered in the Collegian.”

During their time at UMass, this first wave of Black students also developed a close relationship with Black professors in the Afro-American Studies department.

In the early years, the University still did not have the proper procedures and networks set in place to properly support Black students on campus.

“In other words, they didn’t know what to do with Black students when they had problems with, you know, issues on campus and that sort of thing. So, a lot of a lot of things defaulted to the Black faculty on campus,” recalls Allen.

“So, we ended up…being I’d say, the guardians of the students,” he added, emphasizing that this was all “done willingly.”

The Status Report also documents some tension between Black students and faculty, as students’ “attempts to organize were frequently discouraged by some Black faculty members and staff members of CCEBS who feared such union among the students would result in white hostility to the program.”

“The students, however, viewed us with the same suspicion they did white people. Hurt but understanding and not discouraged, we Black faculty and graduate students continued to deal with the task of helping those students through what could only seem to them a tortuous maze of contradictions. We recognized their sense of powerlessness as the same powerlessness felt by those who lectured them not to rock the boat,” the faculty writers continued.

The distance between faculty members and students grew over time, however.

“We started out as a period to be like older brothers and sisters of the students, and now we’re more like, you know, your father. As time went on, and then you become the grandparents of the students,” Allen said.

Allen noted that the Fine Arts Center as a hub for Black art was “a very important area of development” during the 1970s.

Frederick C. Tillis, who ran the FAC at the time, had connections to “luminaries of the artistic world,” according to Allen, and had them preform at UMass. Some included Ella Fitzgerald, the Alvin Ailey dance group and Miles Davey.

The department also brought in artists like Archie Shepp and Max Roach to teach.

“This transformed the whole cultural aspect of Amherst and it had repercussions on the four colleges as well…they would put their resources towards bringing Black artists to the Valley, not just UMass,” says Allen.

“So, it was quite incredible time, you know, from a cultural standpoint. And unbeknownst to us… it transformed what Amherst is. I mean you wouldn’t recognize the old Amherst, having been here because of the kind of support that you have, you know, culturally,” he continued.

This month, UMass announced the creation of a Black Presence Initiative to further explore and document the experiences of Black students at UMass.

The initiative is being spearheaded by the Office of Equity and Inclusion and aims to “document the authentic lived and living experiences of Black community members, as well as create a space for celebrating our campus history.”

In addition to conducting interviews with Black alumni and posting them on the forthcoming website, the initiative is also seeking to create a virtual tour of campus to “explore buildings, landscapes and spaces that defined Black life at UMass Amherst to facilitate understanding by the larger campus community.”

The initiative is also honoring Bracey with a graduate scholarship created in his honor.

Of the Black Presence Initiative, Bracey, who is focusing on the historical side in conducting interviews and documenting experiences, said, “The Black Presence is about the impact of Black people on this campus.”

“I think the broader goal is more transformative than that, you know that knowledge is transformative. And accumulation of knowledge is that people’s stories is transformed,” he continued. “Blackness in the world you live, in the world I live in, is a marker of being misunderstood.”

Bracey also noted that the project is about showing different ways to live in the world and opening up the range of human behavior.

“Part of the Black Presence is to say, ‘if you let us in the door, we can do the work.’ And if you see us here, we’re doing the work. We can do whatever you can do,” he added.

“I don’t know any other university that’s actually doing that because they’d be afraid of the content, you know. But I have carte blanche to let people talk about whatever they want. That’s why they talk. You know, it’s not ‘tell me the good stuff’ it’s, ‘what was your experience like?’ because the story is how do you overcame obstacles not how they breezed through the place.”

“None of them breezed through the place.”

More information about the Black Presence Initiative can be found here. A website with interviews with Black alumni documenting their experiences is expected to be available this summer.

Irina Costache can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @irinaacostache.

James L. Walker • Mar 12, 2022 at 9:52 am

Lieutenant Colonel James L. Walker

George Ruffin Bridgeforth, the first black student to attend UMASS-AMHERST was born in ATHENS, ALABAMA not Athens, Georgia. He graduated from Trinity School which was the same school that I attended albeit sixty-five years after him. He became the Director of Agriculture for Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee and the President of Kansas Technical College, often called “Tuskegee West.” His home is located on Brownsferry Street in Athens, Alabama and his gravesite is at Hine-Hobbs Cemetery in the same city.

Professor Alfred Rosa • Sep 18, 2021 at 1:51 pm

I left the University of Massachusetts in Amherst in 1969 to teach my first classes at the University of Vermont as an instructor in English. Prior to that I taught freshman composition at UMass and part of my responsibility during the years of the late 60s was to teach composition to students of color. I taught my classes at 8 o’clock in the morning in the lounges of the students. My classes were totally of students of color and they would often arrive in the lounges in their pajamas . Needless to say it was a rather relaxed environment. They were good students. Attentive. And the discussions rarely, if ever, turned to any conflicts on campus. It was mostly the principles of good writing that we discussed and tried to put into practice which I think they appreciated . I mark that time as a transformative one for me because I continued on with that work at the University of Vermont where I and others offered a summer enrichment program for students of color from the same communities I encountered at UMass. Those were tumultuous times and I think the plight of students of color, and their problems in adjusting, and the rigors of an academic environment were but some of the many things that we as a society were coping with. I think that living together in the dormitories was a good thing for these minority students rather than being dispersed across the campus and having no sense of community. It was needless to say quite an interesting time for them and really perhaps more interesting for me even. It was education going in both directions.