McKenna Premus/Daily Collegian

UMass exceeds the 2020 Real Food Challenge

UMass dedicates almost 30 percent of its food budget to locally sourced and ecologically sound food

March 29, 2021

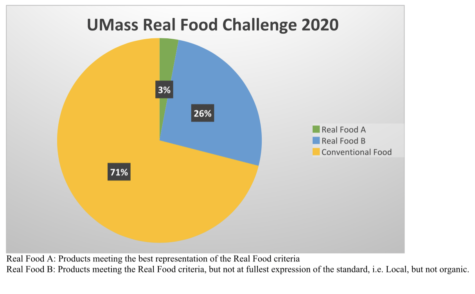

In 2013, the University of Massachusetts was the largest university to sign the Real Food Campus Commitment with the support of students and Chancellor Kumble Subbaswamy. In 2020 it surpassed the 20 percent expectation, dedicating over 29 percent of its food budget to real food.

The Real Food Challenge is a national organization that, through the power of the youth and universities, aims to create a healthier and more eco-friendly food system. Their goal was to reallocate 20 percent of university budgets nationwide away from “industrial farms and unhealthy food and towards local & community-based, fair, ecologically sound, and humane food sources.”

UMass’s Executive Chef of Residential Dining Bob Bankert said that the Real Food Challenge is “really just a commitment to increase not only just our local purchases but our regional purchases, Fairtrade purpose purchases, organic food purchases, really looking at what we’ve purchased over the years and changing stuff to be more sustainable.”

“So it’s just looking at the quality of food that we’re bringing in and supporting local vendors,” Bankert said.

Seven years ago, UMass was only dedicating 8 percent of its budget to “Real Food,” and 16 percent in 2016. Bankert has been at UMass for eight years and he said, “each and every year we have a stronger commitment to what we’re purchasing.”

“Five or six years ago we committed to antibiotic free chicken across campus. Any chicken we used was antibiotic free which was kind of pushing the edge of what was going on in the food industry,” Bankert added. “We talked about it, we connected to sourcing for it, and we committed to do it 100 percent of the way.”

The process of sourcing real food involves larger distributors, aggregators and direct relationships with local farms. Kathy Wicks, the director of sustainability for UMass Dining, said that “Maple Line Farm is less than a mile away from campus and we source the vast majority of our milk right from them.”

“So they’re coming to campus multiple times a week, so that we can serve their fresh, delicious milk. And as you can imagine, not only does it taste better, but it’s also much more nutrient dense because it hasn’t been sitting around.”

“Everything from the milk, to the meats, to the produce is much fresher when we can source it locally,” Wicks said.

Making this food sustainability dream into a reality wouldn’t have been possible without the support of the Henry P Kendall Foundation. Historically, the foundation focused solely on environmental issues, but pivoted to a more narrowed focus on food systems about seven years ago after realizing the extent of that industry’s impact on the environment.

UMass has been a part of their grant making for a number of years, and Wicks said that the partnership has “helped us [UMass] build our infrastructure and do promotional awareness campaigns, as well as bring together more farmers and institutions to talk together about how we can work together. The Kendall Foundation provided the seed money for us to be able to do a number of things.”

“In [Fiscal Year]20, UMass Dining spent close to $5 million on local, healthy, sustainable food… For each dollar the Kendall Foundation invested, UMass Dining has spent five times that on Real Food and the local economy,” Wicks added.

“According to some economic models on multipliers of investing in the local economy, every dollar spent in the local economy can have an impact of $1.60. Even with the challenges of the pandemic, UMass Dining spent $1.2 million on local produce, an increase of $25,000 from FY19” Wicks wrote.

Having a clear definition of what local is allows UMass to more successfully implement and enforce mechanisms for achieving more locally sourced dining. It creates a clearer framework to build off of in the future.

“One of the big things when we started this work was we actually defined what we meant by local, and that at the time was a really big deal. It still is a really big deal, because not a lot of institutions have a very well-defined definition of local” Wicks said.

We have a tiered system of ‘local’. First it is right around campus here in the Pioneer Valley, and then Massachusetts, and then New England, and then 250 miles from campus. So that lets us dip into New York state and a little bit into Pennsylvania.”

If everyone is on the same page about what “local” is, it’s easier to communicate and work together to successfully provide real food to the UMass community.

Making sustainable dining a reality through buying locally sourced food is an extremely collaborative process. UMass manages relationships with local farmers and larger distributors, and those connections can propagate to form an even larger network.

For example, Wicks said that one of UMass’ local farm partners “over time and in large part because of the relationship with us [UMass] become aggregators for other farmers.”

In the winter and early spring UMass begins meeting with local farmers and planning out what they will need for the coming semester.

“It’s building connections in the local areas and giving the farmers a commitment to what we can purchase,” Bankert said.

It’s seeing what they want to grow that’s new, or it’s us giving them some feedback on what we could use more of so they can grow more of it. So it’s really just a working relationship with local farmers to figure out in the past what hasn’t been purchased locally and what we can purchase locally going forward.”

Sourcing locally is crucial in efforts to support the local economy.

“Keeping the financial dollars locally is huge for supporting our farmers. So it’s not being sent to around the globe or out to California farmers, it’s supporting them locally,” Bankert said. “And I think it’s just the trends in the foodservice industry even, you know, with restaurants is the push towards more a local purchasing and, and I think UMass has been a leader of that across a lot of universities and college dining programs in the U.S.”

However, Bankert also noted that not everything can come from farms in the Northeast, “for example, bananas,” he said.

“A couple of years ago we committed to purchasing a hundred percent of the fair-trade bananas all across campus. Again, to support, not a local farmer, but a farmer that could be down in South America, that is now being paid a fair price for what they’re growing,” Bankert said.

While local farmers have played an integral role in the success of the Real Food Challenge, the Student run farm at UMass has been just as important. “One of our favorite partnerships is with the student farm,” Wicks said.

Wicks has been working with the student farm for the past couple of years, “We partner with them and during normal times we have a farmer’s market that the permaculture program and the soup farm do in collaboration. And our purchases have been increasing over the last five years”

“The students actually develop their [own] growing plan and they interview us every year. It’s a new set of students and then they develop their plan from there,” Wicks said. “So it’s been exciting to have them as partners that are kind of learning farmers in progress. It’s been exciting to work with them; it’s such a big initiative and there’s so many working pieces.”

Wicks noted that student engagement has been instrumental in supporting and cultivating other UMass initiatives around sustainability, such as the permaculture garden.

“There were students that had learned of this and came to us and said, you know we see the permaculture work that’s happening now. Let’s take it into the kitchen and onto our plates and really make a difference. We embraced it,” Wicks said.

Bankert felt similarly delighted with the student farm. “They’ve been a huge partner for us over the past years as well. And we actually met with them a few weeks back and talked about fall planting. So each year we increase our purchases with the student farm as well.”

Student engagement is extremely important in sourcing locally to Ken Toong, the executive director of auxiliary enterprises.

“We also try to educate and tell a story about local farms and the food system to students. When [students] graduate you continue to support the local food system,” Toong said.

“I think we do our job because we grow the economy and build communities and support better food for all. It’s so important to us. But we’re not quite happy yet,” Toong said. “We think we can do more with support from students. Also even tracking the dining behaviors, you know, when students join us until they graduate. We see again that buying locally is an important factor for them, so it’s important for us to continue doing that.”

Bankert noted that in New England, since the growing season happens primarily from July to September, it can be “a challenge to figure out what we can buy locally” But, local farms have been increasing their year-round growing by utilizing greenhouses and other new technologies.

‘There’s so much potential in the next three, five, 10 years for this area to grow, and I think there’s going to be a lot of technology that plays a role into that to kind of really figure out what they can grow in the wintertime and make a make a living off of,” Bankert said. “I think we’ll see a lot of fun stuff coming our way in the next five or 10 years.”

UMass’s growing relationship with farms such as Queen’s Greens, located less than a mile away from campus, is evidence of the success of these efforts.

Wicks said farmers have started to “grow [things] under these hoops that’s kind of like a mobile greenhouse. They’re able to actually grow spinach and lettuce greens and, even pea shoots, under these hoops all year round. They do that in the winter and then they’re out in the regular fields in the summer.”

“We can go to them and say we would like to have you grow for us a certain number of pounds every week. So we’ve been able to be a part of them thinking about growing their own infrastructure, knowing that we are a dedicated customer. It’s been a very kind of engaging relationship with a lot of the farmers that we work with”

Not only does this initiative require extensive collaboration externally, but teamwork within UMass has been instrumental in the RFC initiative.

Wicks emphasized how, “Our culinary team is just top-notch. If we can imagine it, they can make it happen. The dining managers and all of the staff here know that it really is about the experience. It’s not just putting the food on the plate, it’s about being there to support students, to be a part of their experience and to support their wellbeing. That happens on so many levels, so it helps to have a good team.”

The Real Food Challenge wasn’t the only challenge that UMass dining faced this year, as COVID proved to be another hurdle. Bankert said that, “one of the biggest struggles that we had was during this time in late winter, early spring, we meet with a lot of the farmers and make commitments to fall planting and what’s that going to produce for us.”

“Our farmers went ahead and planted assuming that [come fall everything would be normal]. We weren’t able to bring out a lot of that product from the farmers, so they had to look to other areas to sell it to you which was not fun to kind of deal with,” Bankert said. “Because you, you want to be able to support the local farmers and when you can’t actually purchase the food that you committed to, because the volume you’re doing again, they gotta find another source for it.”

However, the close relationship with farmers that UMass has cultivated over the past decade in some ways helped mitigate the negative impact of COVID on the local food system. Toong said that open communication with farmers and mindfulness concerning food waste were instrumental in overcoming challenges presented by COVID,

“We always have a way, like a hotline, so that anytime there’s a surplus, the [farmers] give us a call. We even change the menu to use it, to help them as well,” Toong said. “We want to use up what they have; and then the cost, sometimes we give incentives to them as well. I think that open communication was important to our local farmers.”

Despite these challenges, the future of sustainable dining at UMass looks bright. In the upcoming year, UMass plans to focus on becoming more transparent about the carbon impact of the ingredients that are in dishes, expand the permaculture garden, and increase the number of BIPOC vendors that they work with.

Wicks also hinted that “there will be a lot more opportunity for you [students] to engage with a lot of different more interactive and educational events”. Specifically, plans are in the works for UMass to host Diet for a Cooler Planet events and other events to get local farmers on campus and have them interact and educate students and ultimately put sustainable food choices on students’ radars.

A University as large as UMass exceeding the expectations of the Real Food Challenge proves that there is potential for general university adoption of sustainable food practices to set precedent and possibly change the way we as a society approach food sustainability.

“You know, this is larger than us,” Toong said. “I think we have the responsibility to support this new system. Also, we want to lead the rest of our peers. If UMass can do it, you can do it as well. We have proved it to everyone that it’s working. We’ve put in the commitment, met the benchmarks, you know… I think this is what education is all about. As a larger intuition I think we want to lead the way with the support from students.”

Esther Muhlmann can be reached at [email protected]. Sophia Tsekov can be reached at [email protected].