Photo courtesy of Dorcas Grigg-Saito.

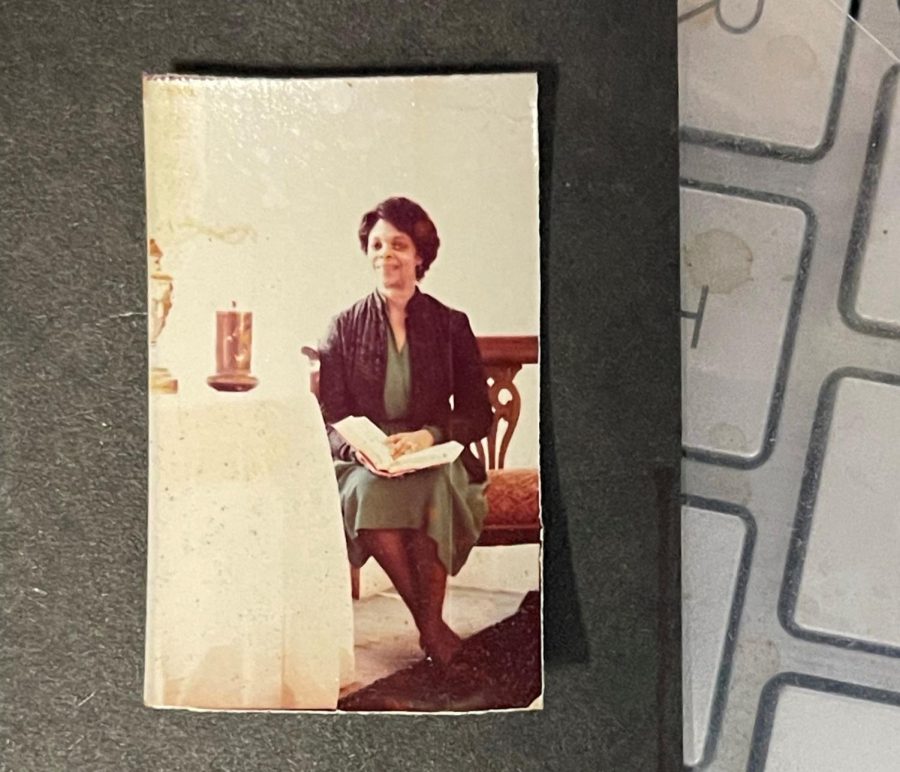

Portrait of a Black woman

How the Black Feminist Archives is preserving the life and work of “ordinary Black women” like Mae Upperman

February 28, 2023

As a child, Mae Upperman remembers sitting on porches with loved ones, talking over lemonade and cookies under the summer sun. This was one of the most joyful parts about growing up as a Black girl, she explained. “Everybody every Sunday was at somebody’s home, and everybody was talking.”

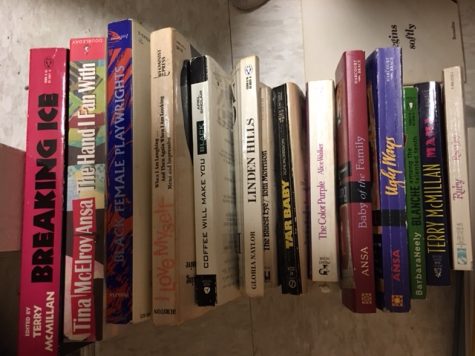

Now in her 80s and approaching the end of her life, Upperman wanted to find a dedicated space for her collection of over 200 books written by Black women, including the works of Zora Neale Hurston and Audre Lorde, among others. But, she hadn’t realized her decades’ worth of undocumented memories and stories were also worth preserving.

So her lifelong friend, Dorcas Grigg-Saito, sought to find a home for Upperman’s collection and came across the Black Feminist Archives at the University of Massachusetts, founded by Irma McClaurin, an alumnus of the University.

The archive, which is dedicated to preserving the work and lives of Black women, resides in the Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center. It carries the work of scholars like Carolyn Martin Shaw and anthropologist Archie Henderson Jones, most of who’s work is unpublished but remains in journals and correspondence that are housed in the archives.

The archive is just beginning to collect the work of “ordinary” Black women like Upperman, women who are not necessarily academics or public figures, but carry unique, untold stories of Black womanhood. But the “Mae Upperman papers,” which will include her books, art and a record of her life, will soon be a part of the archive.

Upperman might have been ordinary in the sense that her work was not widely recognized, but she dedicated her life to advocacy in extraordinary ways. With a bachelors in adult education, counseling and physical therapy from Tufts University, and a master’s in education from Boston University, Upperman worked for years as a physical therapist for the Visiting Nurses Association of Boston.

Much of her career took place during a time where people were starting attempts “to make poverty a priority for the president,” and research aided in rerouting government funding to specific areas of need, Upperman explained.

She worked many years for the non-profit Action for Boston Community Development, which is dedicated to assisting Boston residents out of poverty. She also worked with the Head Start Evaluation and Research Center at Boston University, researching ways to provide “communities with the knowledge of how to handle emotional disturbances of young children within their own indigenous social system.”

Additionally, Upperman developed and managed a center-based early intervention program, in partnership with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, for children with developmental disabilities. Later in her career, Upperman worked to ensure that senior care facilities were meeting the needs of their clients.

“In some ways, Mae represents a person who was working on poverty programs from the beginning,” said McClaurin, describing what Upperman adds to the archives. “We always think that there’s been a Head Start, we always think that there have been these preschool programs for children…those programs came into existence in the 1960s. And she is someone who was working on them early on.”

Between Upperman’s various roles and laborious work with marginalized communities, she never neglected her passion and affinity for art and literature. An avid bibliophile, she wants people to see the “variety of cosmos” reflected in literature and how deeply it can move someone.

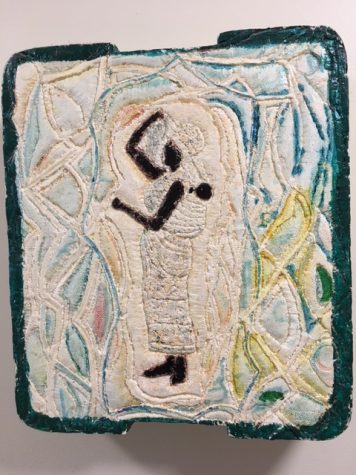

Upperman also creates art and writes poetry herself, reading a passage that begins, “every day, my heart feels lighter from the burdens of past death, which I’ve lived and kept alive. Desperately blowing on the ashes which I strive to keep alive.”

Her visual artwork depicts abstract Black figures. McClaurin sees this work as an advanced creative exploration, despite Upperman being someone who was not formally trained in art. “What might have happened if she had lived in a different time period, or if she had been a different, you know, skin color?” McClaurin said. “Would she have been recognized for that?”

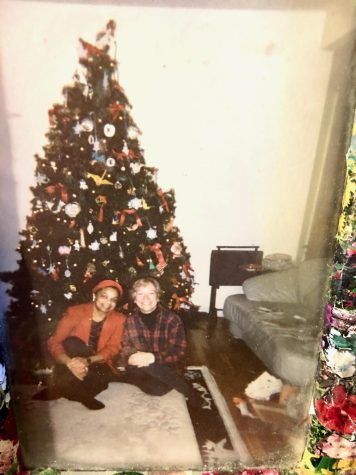

Grigg-Saito met Upperman when they both worked at Visiting Nurses, and the two sparked a friendship that might be seen as unusual to some, she explained. Grigg-Saito was a white woman who grew up in the South and had just moved to the Northeast; she was years younger than Upperman. But, Upperman immediately took Grigg-Saito under her wing, showing her the ropes of living in the relentless Northeast.

“I was having trouble driving in the snow in Boston, and she taught me about driving in the snow,” Grigg-Saito said.

Through their friendship, Upperman taught Grigg-Saito many other things, like her expertise on physical therapy, working with children and the experience of growing up as a Black woman.

Both women grew up during a time of segregation, although they experienced it in vastly different ways. Grigg-Saito, a white woman, grew up in North Carolina and Georgia as the daughter of a Southern Baptist minister who worked to improve the relationships between the Black churches and white churches. Grigg-Saito remembers seeing segregated bathrooms and water fountains, and hostile attitudes towards her father for the work he did.

Upperman was born in 1937 and grew up in Asbury Park, New Jersey, a city that was then segregated with the town line physically separated by a railroad track. The east, which faced the Atlantic Ocean, was a resort for wealthy, white property owners. While the west was home to Black people and Italian immigrants, she explained, who would live and work there throughout the year.

Her school was also segregated, and Upperman vividly remembers when her teachers first started talking about race. Their differences were just skin deep, they would tell the class. This was a form of preparation of the imminent integration that would happen in her school, she explained.

McClaurin also noted the importance of preserving Upperman’s life due to her first-hand experiences with segregation. “She also is someone who experienced segregation when it was entrenched, and then saw changes. And so her perspective on that is really crucial, because we don’t always have [the] historical sort of people who can look backwards,” McClaurin said.

Upperman’s race continued to play a crucial part in her life, far past her childhood. She recalls being excluded from a meeting for the program which she managed, because she was a Black woman.

She also notes her experiences with colorism, in which Black people, particularly Black women, with different shades of skin hold complex feelings of bitterness towards one another. Upperman had a difficult time understanding how that affected people’s perception of her as a lighter-skin woman. “That was another reason for writing, to try to straighten that all out within myself,” she said.

As much as Upperman notes moments of division, she recalls moments of resiliency. She describes the 1960s as a time of great social upheaval and “an unbelievable time.”

“When did you see before that, somebody holding a Black fist in the air and shouting Black power?” Upperman said. In response to a friend who asked her why Black people don’t stick together, she asked “where were you when we were marching and getting hosed down? We were practically glued together.”

Upperman has never been married and does not have children of her own. Among many others in her life, including her nephews and godchild, Upperman holds five women closest to heart; she considers them “heart-sisters,” including Grigg-Saito and good friend Carol Glenn.

“Her expression of love is number one,” Upperman said of Glenn, who still calls to check up on her. “Coming from another Black woman, it’s so beautiful…it’s so natural with her.”

With assistance from Grigg-Saito, Upperman is currently in the process of having her collection and a documentation of her life donated to the BFA and moved to the W.E.B Du Bois Library. McClaurin is in the process of convincing other women, like Upperman, of the importance of preserving their life story.

“Every place I go, I am always interrogating Black women and other non-white women about, ‘what are you going to do with your stuff?’” McClaurin said. “I’m still getting those responses like, ‘oh, I hadn’t thought about it, I didn’t think what I did was that important.’”

The BFA has a simple mission, making sure that Black women are “visible and heard.” As she remembers the joys, pains, changes and constants of her life — and the moments she was told that she must be seen and not heard — Upperman said that having her collection and story become a part of an archive is more than “she could dream [of]… [to have] an idea that could be important enough.”

Saliha Bayrak can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @salihabayrak_.

Dr. Irma McClaurin • Feb 28, 2023 at 12:35 pm

I am clearly biased as the founder of the Black Feminist Archive at UMass, but am indebted to Saliha who is a brilliant writer and has a knack for capturing and revealing untold stories. Thank you for letting us get to know Mae, making her “visible and heard,” and for uplifting the Black Feminist Archive! Ashé!