Sophia McLaughlin preparing to take insulin. Olivia Capriotti/Daily Collegian (2023).

Managing life with diabetes: The perspective from female college students

Two students discuss what it’s like to navigate college with a chronic illness

March 31, 2023

Will you remember to pack a backup supply of insulin for your next beach trip?

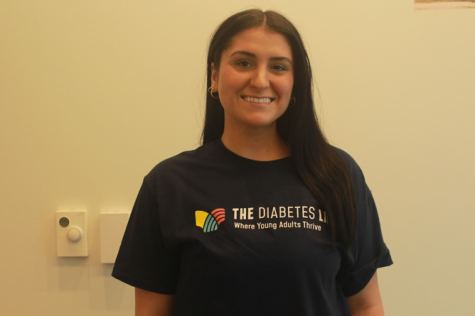

This was a question that Sophia McLaughlin, a junior marketing major, had to consider during her spring break vacation to Mexico. As someone with diabetes, she has to ensure that she carries a variety of supplies, including insulin. There were countless concerns swimming in her mind about what could go wrong over the course of the trip.

“I was so nervous that it would get overheated,” she recalled, worried about her medication being left out in the sun.

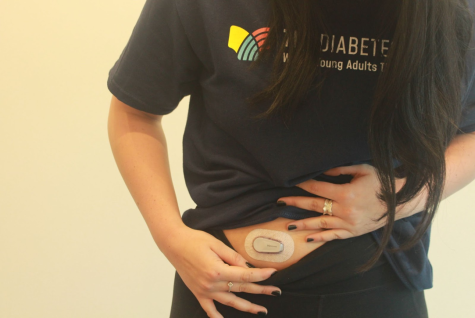

She was also worried about how other beach-goers were going to perceive her body, where a white patch adorned her stomach. This patch, called a continuous glucose monitor, helps to regulate her blood sugar.

“It can be hard to have all this stuff on your body all the time,” she explained. “Especially out on a beach, it took me a lot of confidence to be able to wear a bathing suit.”

A chronic illness is defined as a long-term health condition that may not be curable, and can range from diabetes to cancer. When it comes to diabetes, the body’s pancreas can’t produce enough insulin to regulate blood sugar, and overtime this can lead to serious health problems such as heart disease.

For most people with a chronic illness, such as diabetes, they have what is known as an “invisible” disease. This term is used to describe a lack of visibility around their symptoms.

According to a 2021 report from the Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, misconceptions about chronic illness often occur as a result of this invisibility. While college serves as a period of growth for social, academic and personal lives, among this growth comes stress and anxiety, and for students that are a part of a vulnerable community, this stress can be amplified.

“College is just full of constant times where you’re trying to figure out your life, but I’m trying to figure out my body first,” Mclaughlin said.

McLaughlin, however, is navigating these pressures and creating a community for herself and others. As president of The Diabetes Link at the University of Massachusetts, this leadership position is one way she makes this possible.

Alongside her, freshman legal studies and political science major Jessica Flowers is finding community as well. Flowers began serving as secretary after her first semester at the University.

Flowers and McLaughlin are both type 1 diabetics. Type 1 diabetes is developed early in life, while type 2 diabetes, also known as adult onset diabetes, is developed over time, by way of lifestyle.

For both, life started to change around the beginning of their junior year of high school.

“Everyone was like, preparing for the SATs where I was trying to learn how to calculate my own blood sugar,” McLaughlin said.

Growing up, McLaughlin was active in sports — she loved to play soccer. But come the middle of her junior year, she started to notice a difference after her practices.

“I had so many photos in my camera roll of myself and like, you could see how I was getting smaller and smaller,” said McLaughlin, emphasizing the gradual but concerning process of her weight loss.

McLaughlin was confused by how her appearance was changing, despite her active nature. She had never experienced any issues with her health up until this point in high school, and would go two months without knowing she had diabetes.

Within a month and a half McLaughlin had lost up to 30 pounds, and said that she was so skinny to the point that she couldn’t play soccer anymore.

“I would be at practice and I would just be standing there, like I couldn’t breathe,” she said.

For two and a half days she was hospitalized and recalled how little she knew at the time in relation to how diabetes would impact her.

“It takes a toll on your life. I’ve had it for four years now, but during that time I had no motivation, I was so irritated and so upset. I didn’t know why my body was like this,” she said.

For three months, Flowers experienced symptoms such as constant thirst and frequent urination, which she would later learn were signs of high blood sugar. But it wasn’t until after this three-month period she would receive a diagnosis.

During January of 2022, Flowers received her diagnosis the day after her 18th birthday. She would go on to miss several days of classes at Ipswich High School, where there was a lack of support from her teachers.

“A lot of my teachers didn’t really realize, they weren’t educated on diabetes. It was a lot of like ‘Oh, you can’t take the test today?’ rather than asking how I was doing most days,” she said.

The reality soon set in that these persistent symptoms of fatigue and thirst weren’t going away. This left a mental impact, not only from physical pain, but the acceptance and change it takes to deal with a chronic illness.

Flowers initially struggled to adjust to her new diagnosis, finding it difficult to manage her blood sugar levels while attending classes and studying for exams.

“Being diagnosed with a chronic illness is debilitating and it is so hard, especially right after you find out,” Flowers said. “Your perception of the world completely changes, it’s so strange.”

Stress is inevitable when navigating college and is one of the biggest things that can worsen a chronic illness. For diabetics, stress can lead to high blood sugar; for female individuals with diabetes, having a period can raise their blood sugar levels.

Danielle Madden, a licensed social worker at UMass who helps to oversee the Chronic Illness Support Group, explained that there is a “huge mind-body connection” when it comes to the health of chronically ill students.

For these students, a time of particular stress can include navigating medical appointments or just accessing classes without proper guidance. Students can feel like a burden when seeking out support, Madden said.

Flowers also talked about the mental preparation she has to go through every day when it comes to her blood sugar, something that she didn’t experience before her diagnosis.

“I’m constantly thinking about, like, what is my blood sugar? What am I eating? Like, what am I doing next? How is that going to affect me?” she explained.

Flowers was involved in several extracurriculars at her high school, where she was constantly interacting with her peers and the community. She also took honors and AP classes which are notoriously rigorous, though after her diagnosis, all of these aspects of her life were a lot to handle.

“All these other kids had time to really concentrate on stuff and meanwhile, here I am in the nurse’s office dosing,” Flowers said.

Regulating blood sugar levels for a diabetic is difficult without insulin injection. Since her teachers didn’t allow for her to take insulin in class, a cloud of guilt formed from having to prioritize taking it at certain times in the day.

“I was frustrated with the way they [teachers] handled me taking insulin,” Flowers said. “It’s such a daily thing. I do it in public, and I can’t always afford to leave the room. It kind of adds to the stigma around diabetes.”

The stigma surrounding insulin intake that her teachers perpetuated is indicative of broader cultural issues, like the misconceptions about the intersection between food and diabetes. According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, eating disorders are prevalent among 20 percent of diabetic people.

Flowers has received comments from people who are surprised to learn she has diabetes, noting that she isn’t overweight.

“It’s a very uncomfortable situation to be in, with people commenting on what you do consistently. They comment on what you eat or what you look like,” Flowers said.

Diabetics have to keep in mind the glycemic index of food, which designates how quickly or slowly blood glucose will rise after eating. When an individual has diabetes, it’s important to keep track of which foods have either a low or high glycemic index. For example, processed foods tend to be on the higher end of the scale because they are easier to digest.

It can be difficult, however, to estimate this measurement, and Flowers explained that there is still a stigma around the eating habits of diabetics — she has experienced it firsthand.

“I had a cookie out and some guy walked past me and saw me inject insulin, and then turned around to point at my plate and said, ‘Oh, and you’re having that?’” she recalled.

Carbohydrates in food are what have to be accounted for the most, as they are converted into blood sugar after being digested. Sometimes Flowers will take more insulin than needed, and as a result, she becomes tired.

“I feel almost drunk, and it’s such an unpleasant feeling and it’s really hard to function. You just get super, super sweaty, and it’s kind of like a disconnect from the world,” she said.

A part of college is about navigating not just lifestyle, but the culture of the campus. When it comes to drinking in college, diabetics have to think harder about the decisions they make; drinking impacts everyone, but the consequences can be more severe for students with a chronic illness like diabetes.

Alcohol can lead to an increase or decrease in blood sugar levels, and for people with type 1 diabetes such as Flowers and McLaughlin, excessive drinking can drop their blood sugar to dangerously low levels. Also known as hypoglycemia, low blood sugar symptoms include difficulty in concentration and blurred vision, and even worse, can lead to seizures if levels remain low.

“It’s easy to feel ashamed if you’re not taking care of your body the way you should,” McLaughlin said. “Especially as a college student, it’s a lot about finding the time to exercise, to eat healthy or the time to drink. But you know your body can’t handle it the way other people’s can, and you still want to go out and have fun.”

Aside from academics and unexpected dining hall interactions, diabetes also impacts the personal relationships of individuals. From platonic to romantic relationships, navigating these experiences can be exhausting; dating in college with a chronic illness can bring about feelings of frustration and isolation.

McLaughlin described that her former boyfriend rarely asked questions about her health, and never tried to learn about what it’s like to have diabetes.

“I’ve definitely hesitated to tell guys when I first start talking to them,” she said. “Having diabetes is not who I am, but you’re going to know sooner or later. It’s just about finding that balance of telling someone but also not feeling that you’re oversharing.”

At the time of McLaughlin’s diagnosis, she was unsure of how to process what would become a major change in her life, not wanting to explain it to her friends.

“I had all my friends, but none of them knew a single thing about diabetes and they wanted to. I think I just felt that I had to figure it out all on my own,” she said.

For Flowers, she described that when it comes to social gatherings, people can perceive diabetics as “flaky” for not being able to hang out, when in reality, they might be experiencing a period of low blood sugar that day.

“You cannot function like a normal person. So people will be like, ‘Oh why are you not able to do this?’” she explained. “I can’t just go with them, for a swim or walk that day, whatever. It seems like you’re being a bad friend at times when in reality, you just physically cannot handle it.”

After recognizing that her diabetes was a permanent condition, Flowers mentioned that it has made her a more resilient individual. Similarly, McLaughlin expressed that her diagnosis has given her a fresh perspective on life.

As they work on expanding their support system within the campus community, Flowers and McLaughlin aspire to encourage other students with diabetes to join and feel acknowledged.

“We need support from each other. We need to be able to have conversations and just not feel any shame, not feel like we’re completely alone,” McLaughlin said.

Olivia Capriotti can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @CapriottiOlivia.