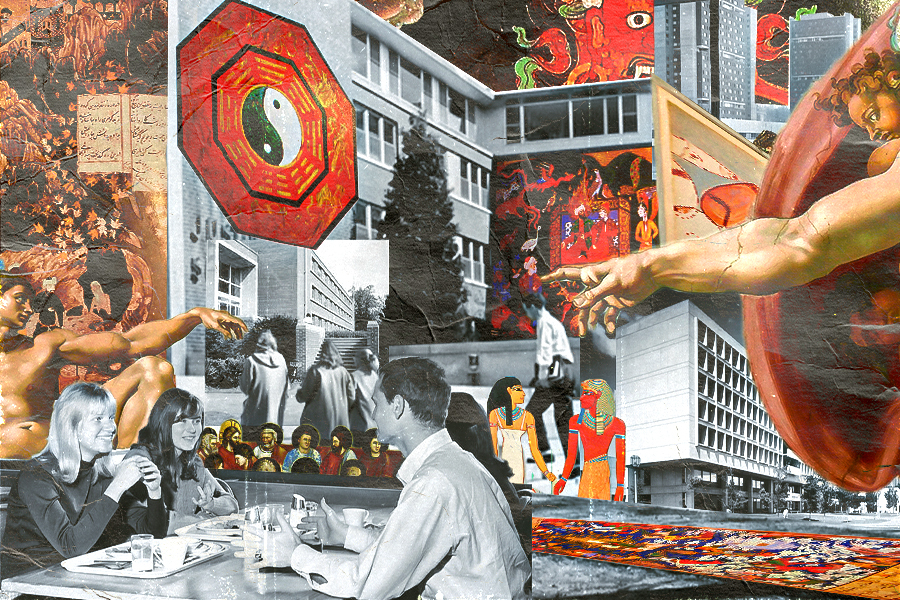

Graphic by Nick Archambault

Studying religion at UMass made me a better thinker — don’t be afraid to give it a try

Reflections from a curious secular student and a conversation with honors history professor Dr. Susan Ware

March 6, 2023

It’s a funny coincidence that I discovered the song “Personal Jesus” by Depeche Mode while taking a course on the history of Christianity.

The refrain, “Reach out, touch faith,” played in the background while I wrote my essays. This ‘80s new-wave rock song felt like what I had been trying to do since entering college. I was trying to reach out, not necessarily to touch faith, but certainly to understand it.

I was raised secular and have never participated in any organized religion, but religion and its’ rituals have always been on my periphery. My paternal side has Lutheran roots; I recall the Noah’s Ark tapestry that hung above my great-grandparents’ couch and the large Bible on their coffee table. My maternal side is Chinese and immigrated to America in the 1980s; we have a Buddhist shrine of a Chinese Bodhisattva in our house and have, on occasion, lit incense for it.

As a child, I was mystified by the snippets of names, places and stories I heard in passing. I asked my great-grandparents, “Who was Mary?” The one instance when I attended a Christmas Eve service with them, I was amazed by the solemn beauty of the hand-held candles. I didn’t understand the sermon, but a poignancy emanated from the congregation as a hundred voices sang a hymn.

From a secular upbringing, I believe that all humans can know what sacredness feels like — with or without participation in a religious institution. There are many things that can make us feel sacred: time spent with a loved one, nature, a song or a piece of artwork.

By the same token, I disagree with the belief that this ability therefore renders religion and its’ rituals superfluous. Participating in the occasional ritual helped me understand my family’s cultural history far more than simply studying historical texts. Rituals, as relaxed and infrequent as they are in my life, offer a new branch of wisdom.

For example, when I visited China, my family and I burned paper money to venerate our ancestors. As I placed the joss into the flames, I honed my own intentions toward thanking a lineage that I had never met, but with whom I was inextricably tied.

That summer day, in this generational village on the Chinese mountainside, I watched as the gold and silver paper curled against the embers and their precious ashes floated upwards. The ritual of burning joss paper created a deep familial dialogue that’s beyond what I can logically explain.

The beauty in ritual is what initially attracted me to the mystery of religion. However, I also observed that religion is a heavily charged topic, ingrained in politics and cultural vitriol. As my religious studies professor Dr. Susan Ware said, “When I look out at the world, I see so many vehement opinions about religion and so few facts.”

I’ll admit, I had very few facts. It wasn’t until I arrived at the University of Massachusetts that I knew where to start looking.

Between the business and economics courses I was taking for my major, I managed to squeeze in Intro to World Religions 112H, taught by Ware. Her course outlined six majority-populated religious traditions; we spent the semester following the chronology of their development while discussing their origins, scriptures, fundamental beliefs and aesthetics.

From Kabbalah mystics to tales from the Ramayana, the themes of religion, both historic and spiritual, resonated with me deeply. In other words, I couldn’t get enough. The next semester, I enrolled in History of Christianity 225H, also taught by Ware.

I have finished both courses and I can confidently say that studying religion has transformed me into a better student, citizen and thinker. I strongly encourage my peers to give religious studies a try.

From an academic perspective, studying religion at UMass has been incredibly heartening. I saw that religion could indeed be discussed both critically and respectfully — certainly a breath of fresh air from the reactionary religious discourse in modern media. In fact, I was almost as fascinated by the pedagogy as I was with the content itself, and I recently interviewed Ware about her goals in teaching religion.

“If I zoom out, I have a very deep commitment to spreading religious literacy,” she said. “I want my contribution, my legacy, to be that I spread knowledge — respectful, compassionate knowledge — of the beauty and the foibles of the different religious traditions.”

Religious literacy allowed me, for the first time in my life, to start talking about religion with my peers. In my History of Christianity course, I befriended three classmates. One was raised in the Greek Orthodox tradition, one was raised in the Catholic tradition and the other was raised without a religious institution. Over coffee and chocolate chess cookies, we talked for hours about our views on spirituality, Christian history and rituals.

One Sunday morning in November, we donned shin-length dresses, piled into the back of a Honda and drove to the center of Holyoke to attend a Greek Orthodox divine liturgy service. With some guidance from our Greek Orthodox friend and the priest’s welcoming wife, we had the privilege of observing this beautiful hour of worship.

The gorgeous murals, gilded cloths, incense and Byzantine chanting were unlike anything I had witnessed before. This exposure added a richness to my college experience that I likely would not have found on my own.

I also found richness in debates and disagreement. Discussing something as complicated and morally inconclusive as religion has been an arduous lesson in balancing critical and compassionate thinking.

On one hand, religion has sculpted written languages, artistic movements and civilizations. On the other hand, these traditions have been tied to numerous wars, genocides and corruption. The lack of clear answers in religion can be bewildering in the classroom.

Ware mediates this by teaching religion from a historical perspective. “I teach the history of Christianity and also world religions as history classes, describing what happened rather than taking a side about whether it was legitimate or whatnot,” she said.

“I do feel an obligation to bring some neutrality. I don’t know if objectivity is possible, but certainly some neutrality paired with respectfulness,” Ware said. “It is not my desire to either glorify religions … or gloss over the faults in any tradition.”

When studying religion, especially from a historically based perspective, I’ve found that many students (myself included) have the impulse to perform moral calculus on the historical “good” and “bad” aspects of a religion. We seek to ease the dissonance of its’ contradictions and reach a legitimate answer.

Over time, I realized that this goal is immaterial and impossible. What’s most important is that students continue to grapple with religions’ dual consequences — some abhorrent and some beautiful.

By recognizing the capricious ways that religion has interacted with human history, we can see beyond the common narrative that history was predetermined and that things were always destined to be the way they are today. This idea can help us become open-minded, and I believe that the process of reckoning with religious history is a hard yet fruitful journey.

“In Judaism, the image of a faithful Jew is someone who continuously wrestles with God … What is forbidden is to walk out of the struggle or to walk out of the wrestling ring,” Ware said. “To continue the love and the hate and the fear and the doubt is itself the religious process.”

Though this model is faith-based, I believe that it can also reflect the dissonance that everyone faces in the process of learning. I am thankful that I am at a place where I can interrogate the world. By extension, I don’t think we’re supposed to come up with a conclusive answer. That’s the point.

Why study religion in college? When else will we be surrounded by peers who are so willing to swap burgeoning insights? Where else will my surroundings be so receptive of my own? The act of digesting such layered material has forced me to exercise control over my impulses of judgment and confirmation bias.

In his argument against Hamline University’s decision to fire a professor for showing a 14th-century artwork of the Prophet Muhammad in her history class, Dr. Omar Safi, a professor of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at Duke University, stated, “Some part of the educational process does call for stepping beyond each one of our vantage points enough to know that none of us have the monopoly on truth.”

In an age when most of our opinions are gleaned from news and social media, it is essential for us, as students, to learn how to slow down, think critically and challenge our own preconceptions. In this way, perhaps, we can become more compassionate, confident and civil adults.

“Students today will be tomorrow’s politicians, scientists and even workers,” Ware said. “With a respectful and critical understanding of another tradition, the big goal would be to avert the next religious genocide. That’s a lot to expect from a few classes of 24 people at UMass Amherst to change the world that way, but it’s moving the current in the direction that I feel is imperative.”

“We will be meeting people from a number of religious traditions and from a secular skepticism about religion. With some knowledge, there’s a way to connect to people of another tradition,” she said.

Ware suggested that studying religion could help build relationships and greater understanding in the personal and professional sphere. For example, when working with a Muslim colleague who may miss a meeting to attend to a daily prayer, she explained. “Maybe I work in an office with a Jewish colleague, and I say ‘Oh, did you ever look into the Kabbalah?’ and I have things that can form a connection,” Ware said, as another example.

“I think making us more civil in our civic space and our workspace is important and, bit by bit, maybe even creating societies of voters who are less prone to ignorant persecution of other faiths,” she said.

I could go on and on about the cognitive exercises and discussions that arise from studying religion, but I love this discipline for another equally important reason: I find it beautiful.

Again and again, I’ve felt the subtle dismissal of the humanities. We seem to have reached a widespread opinion that studying the humanities is only justifiable because it gives engineers and businesspeople better soft skills. The dismissal is particularly potent for religious studies. Currently, the only religious studies program at UMass outside of BDIC is an 18-credit certificate program held through the Humanities and Fine Arts department and Five College Consortium.

Ware noted that there is skepticism surrounding religious studies. “We’re in New England, an area of so much higher education and…[it’s] secularized more than other parts of the country … so some students probably come in thinking religion is complete nonsense and it’s ‘not science, not science, not science,’” she said.

“We know that science has arrived at all sorts of truths, at all sorts of cures for illnesses — and I will just confess that nobody respects the scientific method more than I do — but at the same time, there are things that religion has brought to human history,” Ware said. “To remain just ignorant of those [factors] because I can’t cash it in for a consulting job, I think, is a shame.”

She acknowledged, “That really comes from my sense of what is a good life. I can enjoy a certain richness that comes from cultivating the mind [when] learning about experiences that have shaped human lives [and] that have shaped the formation of human civilizations. To me, that’s just a much richer life.”

In his opinion piece for the New York Times, Jonathan Malesic, a Texas-based professor who taught theology for 11 years, wrote “The human mind, though, is capable of much more than a job will demand of it. Those ‘useless’ classes like philosophy, literature, astronomy and music have much to teach.”

“I haven’t had to solve a calculus problem in 25 years. But learning to do so expanded my brain in ways that can’t simply be reduced to a checklist of job skills,” Malesic wrote. “Living in the world in this expanded way is a permanent gift.”

I think back to the joss paper I burned in China and the candles during the Christmas Eve service. Why go the extra mile to have such indulgent gorgeousness in our lives? There’s more to being a human than living for the sake of work and production. We have hearts that can be stirred by tender moments of love. We inherit questions and stories from before our births that scaffold our identities. We have the capacities to crave these soft moments of veneration, and we ought to indulge in them. It’s not a luxury. It’s living.

Take my word for it when I say that a student doesn’t have to be religious to appreciate and respect religion’s impact on humanity. To scorn religion completely is to ignore a whole realm of richness that comes from being a human. To scorn the study is to pass up an opportunity to understand our shared humanity.

“As I’ve studied this for so many years, I am less and less interested in the question of ‘what is true within a religion?’ or if there’s one religion that is true and the others are not, and much more interested in asking if they’re beautiful,” Ware said.

“I’m just less interested in the questions of cognition and more interested in the revelation of beauty through the tradition,” she continued. “The beauty does open me up inside, in parts of me other than my cognitive capacities, and that feels more sacred.”

Kelly McMahan can be reached at [email protected].