Nina Walat/Daily Collegian

What Went Wrong: Part I — The Dorms

“There had to have been some foresight that there would have been an explosion of cases”

February 13, 2021

“It’s normal.”

“Think of an absolutely normal time in Southwest — whether it’s the lowrises or the towers —and it’s dumbfounding how normal things are,” a University of Massachusetts resident assistant said.

He doesn’t mean “pandemic normal” — he means normal normal, with many students behaving as if this were any standard year on campus.

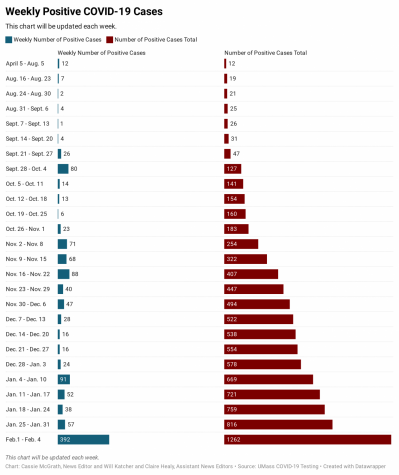

In the first week of UMass’ spring semester, a term in which the school widely opened the doors of its residence halls, coronavirus cases skyrocketed. More than 400 positive tests in the span of five days forced the University to raise its risk level to the highest possible mark, thus halting in-person classes for at least two weeks and requiring a self-sequester for all students living in the Amherst area.

Beginning Sunday, when the school raised its risk level to “High” and told students to remain in their residences, the Recreation Center and other campus buildings have been closed, a policy that will continue for at least two weeks. Leaving dorms to walk around campus, the school said, was not permitted, a policy it later rescinded.

Theta Chi, a fraternity on campus, drew intense focus and the ire of the school community last Saturday after the Daily Collegian reported that the chapter threw crowded, back-to-back parties the previous weekend that disregarded coronavirus health guidelines.

The fraternity has been placed on interim suspension while the school investigates, but it was more than just these parties that caused the outbreak.

An in-depth Daily Collegian investigation, reported here and in two other parts to be released in the coming days, tells the story of what went wrong at UMass, revealing the origins of a COVID-19 outbreak that can hardly be blamed entirely on members of the Greek life community.

Part I: The Dorms

Over the course of seven days preceding the start of classes, 5,300 students arrived at their residence halls. Move-in times were spaced out from Jan. 25-31 to enhance distancing between students and families. UMass required the students to be tested for the virus once upon arrival and again four days later, and asked them to limit their interactions until receiving the results.

But many students disregarded the final instruction, multiple resident assistants said.

Three RAs, referred to in this piece as Erica, Cameron and Sean, are identified by alternate names out of fear of retribution from school administration or their residents. James Cordero, co-chair of the Resident Assistant/Peer Mentor Union, confirmed that the three sources are RAs and verified their statements.

“I think my close RA friends and I knew s— was really going to hit the fan about the second day of move in, when it occurred to us that kids are going to be here all week with no classes,” said Cameron, an RA in the Southwest Residential Area.

From the first day of arrival, students were expected to adhere to reduced occupancy restrictions in their dorm rooms — including a limit of one additional occupant beyond the room’s residents. When outside their rooms, they were asked to wear a mask and socially distance. No guests were allowed into residence halls.

“I think the common consensus was to not follow that,” said Chris Brady, a freshman economics and political science double major and senator in the Student Government Association. The four-day “quarantine period” between arrival tests, he said, was “not really respected.”

Brady didn’t see any huge parties, he said, but there were many instances of groups of students hanging out together in the dorms.

“Stuff that, although we’re in a pandemic, should be reasonably expected of college kids who haven’t interacted with other people in a year,” he said.

Brady was moved into quarantine in the UMass Hotel after coming in contact with someone who tested positive for COVID. He hadn’t been to any parties or interacted with anyone who had, but like many other students, he hopped in and out of dorm rooms to meet people being as safe as he could.

“To them, this is college. To them, the risk is low. And it honestly used to be pretty low,” Brady said. “There’s that freshmen insecurity, you’re new here, you don’t know anyone, you want to make sure you get your friends quickly. It’s just tough.”

In the first week after students arrived, multiple RAs described responding to rooms with well over a dozen people packed inside, some with music and lights on — a regular occurrence for a dorm party in another year, but a dangerous situation now. Cordero said multiple members in the RA/PM Union had reported dorm rooms filled with more than 20 students.

“You knock on the door and hear, ‘Everyone, do you have your masks on? Get your masks on,’” said Andrew Zhu, an RA in Moore Hall in Southwest. “It’s very obvious that prior to us knocking, they’re not wearing masks.”

RAs live alongside their residents and use the same bathrooms, water fountains and other facilities, giving both them and students obeying the rules little room to avoid those flaunting safety guidelines.

What makes the situation more difficult for those tasked with supervising students is the uncertainty the virus carries — people may go more than a week without realizing they have it; others never show symptoms.

On several occasions, Zhu heard students talking in the halls about having the virus or showing symptoms, making him second-guess responding to rooms with many people in it. “I just have a scratchy throat, don’t worry about it,” Zhu remembered a resident saying through a closed door.

Zhu said he’s also overheard students mocking RAs for enforcing safety protocols such as mask-wearing. Three different RAs described defiant students, boldly unwilling to wear masks or follow the health guidelines laid out by the school.

Multiple RAs reported similar incidents to Cordero: students telling them, “I’m here for my college experience. I’m here to have as much normalcy as possible, and if you’re getting in the way of that, you’re ruining my college experience.”

One resident was under the impression that he could “do whatever” once his four-day arrival “quarantine” was over, he told Erica, a Southwest RA, referring to the University’s request that students limit their contacts while awaiting their arrival tests. “He said he wasn’t going to listen to me because he thought we were making up rules by ourselves about COVID safety.”

Sean heard students echo a similar sentiment, believing they can live “a free life” after completing the arrival quarantine.

“There is no plan for what to do for big crowds or anything,” Cameron said. “They seem to think that the only thing we can do is write kids up.”

In a survey sent to members of the RA/PM Union, many RAs reported that floor common rooms had been a major hub where students would gather without masks, Cordero said.

But writing students up for violations is a time-consuming process, one that he feels is unlikely to result in a meaningful outcome.

“If we were to document people every time there was a technical rule violation, we would be doing it literally nonstop,” Cameron said. “You walk around, and there’s big groups in the halls. You tell them to disperse, they’ll disperse, maybe they’ll go to other places.”

Multiple other RAs said they don’t feel that reporting unsafe behavior will result in consequences for the students.

“There’s not much motivation on RAs’ ends to fill out incident reports because there’s an extreme lack of enforcement on the University’s part,” Zhu said. “I’ve heard that students just received letters, and I understand that in normal years, breaking university policy would receive you a meeting with an administrator.”

Sara McKenna, the SGA secretary of university policy, said UMass administrators confirmed that students were asked to leave campus for violating health and safety policies. But McKenna said that the sanctions are confidential to protect student’s privacy.

“I think students are starting to get frustrated. They’re seeing a lot of violations be sanctioned with [a reprimand], and students kind of take it as, ‘Okay, well, I didn’t get in trouble. So, I can move on and violate something else,’” she said. “But I do think it’s important to start with education, to a certain extent, because we have a lot of students who, it may really just be one conversation with a dean that makes them realize the impact of their actions.”

The SGA is encouraging students to report evidence of conduct violations to the Dean of Students Office.

Attempts to enforce student conduct on campus are like “whack-a-mole,” Hayley Cotter, a Ph.D. candidate in English, said. Early in the semester, she described students studying maskless and undistanced near her office in South College, an area supposed to be off-limits to students, but not adequately labeled or sectioned off as such.

“For every student you say to put on a mask or to socially distance, you have five more” who don’t follow precautions, she said. “It’s kind of a losing strategy.”

Equally discouraged are residence hall security staff.

Rachel Sweeney, a security monitor, said she can hear alarms going off in buildings as students open back doors for their friends to enter, bypassing the sign-in desk.

Dorm security was absent from residence halls during the first week people were on campus, leaving students able to enter their friends’ dorms at will.

Even when regular security started on Jan. 31, staff only worked normal shifts, which begin each night at 8 p.m. Students regularly evade security by simply entering other dorms before the monitors’ shifts begin.

“If they want to actually enforce their guest policy they need to have people at the desks for longer,” Sweeney said.

She added she has seen students sprinting between residence halls, trying to slip in unobstructed, as she arrives for shifts.

Most students are not disregarding COVID-19 rules, Brady said.

“We’re not all like this. The vast majority of us just want to tough this out and be here,” he said. “Not everyone is partying.”

On Monday, Ed Blaguszewski, a UMass spokesperson, said that more than 350 students had been referred to the Dean of Students Office for violating the Code of Student Conduct, in many cases, due to breaking health and safety guidelines.

Nearly 95 percent of those facing sanctions were first-year students, Blaguszewski said.

On Friday, Ed Blaguszewski confirmed that there had been four suspensions, nine “interim sanctions requiring removal from campus housing,” and four “completed cases of removal from campus housing” under the disciplinary process. 70 cases were still under review, he said.

Brady believes that both the University and the students are responsible for the outbreak. With the deficit that UMass is facing on its balance sheets, he said he can empathize with the school’s decision to open the campus. In August, UMass announced a $168.6 million dollar budget deficit, $67.4 million of which came from lost housing and dining revenue.

“But there had to have been some foresight that there would have been an explosion of cases,” Brady said. “You bring back 5,000 kids, with no enforcement of the rules — that’s just asking for something to happen.”

But on the other hand, “everyone knows the rules,” Brady said. “Everyone knows what is safe and what isn’t safe. Kids are disregarding that, and that’s on them.”

In a statement Friday, Blaguszewski said that “Inviting students back to campus for [the] spring semester involved extensive preparation and planning.

“As part of that preparation, the university made clear and consistently communicated the need for students to follow important public health protocols. Compliance among some students regarding mask wearing and social distancing, as well as compliance for the short quarantine period at the start of the semester, did not meet expectations.”

“I think that administration has failed by trusting a bunch of 18-year-olds that don’t have any reason to be on campus, other than to be in college,” Sean said. “Many of these students that are coming don’t have in-person classes, so they have no options other than to stay in their dorms.”

But students, Sean said, should also know by now what’s acceptable behavior during the pandemic.

“It’s hard to give people the benefit of the doubt, a year into a pandemic,” he said.

Even if the virus is less likely to harm young people, Sean said they have a responsibility to protect those at UMass with underlying health conditions, as well as the permanent residents of the Pioneer Valley.

“The fact is we don’t live in a bubble,” he said.

“UMass made a very, very dangerous gamble on the assumption that 18- and 19-year-olds would follow the virtual contract that they [signed],” Cameron said, referring to the agreement to follow certain health protocols students committed to before arriving.

But Cordero, the RA/PM Union co-chair, said he wouldn’t call it a gamble.

Instead, he called it “a calculation,” on UMass’ part, that it could manage the spread of the virus across campus.

“It was inevitable that COVID would come,” Cordero said.

———

This article is part of a three-part series exploring the spread of COVID-19 through the University of Massachusetts at the opening of the spring semester. Part II, The Contact Tracing, can be found here, and Part III, The Quarantine, can be found here.

Will Katcher can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @will_katcher.

Sofi Shlepakov can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @SShlepakov.

Cassie McGrath can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @cassiemcgrath_.

The Daily Collegian News Section can be reached at [email protected]. Follow them on Twitter @CollegianNews.

Steve Crowe ‘71-74 MDC staff • Feb 15, 2021 at 9:25 am

This is award-winning reporting and writing. I can’t wait to read Parts 2&3.

Alana Zeilander • Feb 14, 2021 at 1:42 pm

This is an amazing piece of journalism! Thank you for reporting on such an important aspect of our situation at umass.