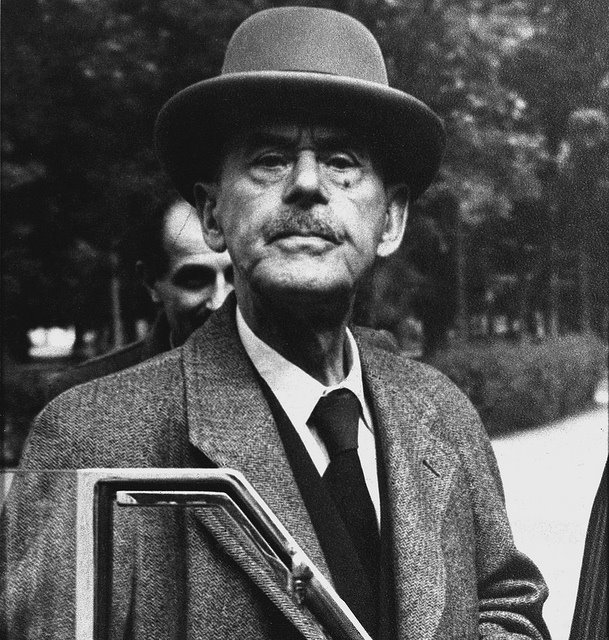

Look up “global warming plus grandchildren” on Google and you’ll find 585,000 responses, writes environmentalist Bill McKibben in his newest book, “Eaarth.” Politicians and movie critics from the likes of Bill Clinton and Roger Ebert and, ironically, corporate icons like Richard Branson, chair of Virgin Airways, all use nearly-identical rhetoric to describe the guilty parts we play as creators of the hot, thirsty world that awaits our grandchildren. The problem, according to McKibben, with these moralized calls to action is that they are all lies. That hot, thirsty world we’re trying to keep our grandchildren from encountering? It’s ours already.

Welcome to Eaarth, a planet so irreconcilably different from the one we lived on not more than half a century ago that McKibben merited it a different spelling. The average temperature of the planet has risen a degree and a half Fahrenheit. Arctic melt has accelerated to such a degree that within a decade or two, “a summertime spacecraft pointing its camera to the North Pole would see nothing but open ocean.”

The consequences of these phenomena have been observed across the globe. While the tropics expand – a further 8.5 million square miles, to be precise – they push the dry subtropics ahead of them. In 2008 in Australia, half the country was in drought and the following years have seen no improvement.

McKibben writes in the book that the executive director of the Water Services Association of Australia said, “We are trying to avoid the term ‘drought’ and saying this is the new reality.”

In response, McKibben wrote “They are trying to avoid the term drought because it implies the condition may someday end.”

And in America? In 2008, hydrologists in the United States predicted drought across the American Southwest had become a “permanent condition.”

McKibben shoves statistics like these in front of his readers with little concern for their fragile consciences. More than once I found myself staring sheepishly at my white, 1992 Ford Taurus before opening the door and starting the engine. I smiled queasily at the vendors of a roadside farmer’s market on my way to the supermarket to check out the specials on deli meat and strawberries. At least I remembered to bring my reusable bags?

But it is important not to confuse my guilt with resentment. The importance of this book to the world, particularly to developed countries, the largest global consumers of fossil fuels, far outweighs the discomfort experienced by the average American as he or she reads it. Three hundred and ninety parts per million of carbon dioxide flood our atmosphere today. That’s 40 parts per million above the “safe” amount projected by James Hansen, the planet’s leading climatologist.

By “safe,” he meant the number at which droughts don’t become permanent, storms caused by increased oceanic temperatures don’t routinely turn into severely damaging hurricanes, and the Arctic ice cap doesn’t melt.

Kevin Anderson, a scientist presenting at Exeter University in 2008 during a conference on global warming, predicted before an audience of leading climate scientists that it was “improbable” that the world would be able to stave off 650 parts per million in the years to come. Six hundred and fifty parts per million equates to a rise of seven degrees in the global average temperature.

And you thought this summer was hot.

In a normal world, problems – even big ones – respond well to “comfortable” solutions. Comfortable solutions allow us humans to continue to burn our oil, mass-produce our food, and grow our economies exponentially.

But this is Eaarth. Things don’t work the way they used to. To accommodate this change, McKibben proposes solutions that will seem radical to a business major. He applauds Woody Tasch, founder of the Slow Money movement, which hails a steady, three or four percent return for businesses over a 20 percent annual gain. He’ll take Berkshares – a local currency native to our very own western Massachusetts – over greenbacks any day. In McKibben’s utopia, suburban families use their yards for gardens instead of pools.

Weaning ourselves off of fossil fuels, off of exponential economic growth, off of high fructose corn syrup and imported strawberries in the dead of winter, won’t be “comfortable.” But it will be necessary; it is necessary. McKibben’s wry humor carried me through what was a largely depressing book, and his recounting of a few promising figures such as “…the consulting firm McKinsey estimated in 2008 that existing technologies could cut world energy demand 20 percent by 2020” might just carry me through what is a strongly fought-against transition.

Bill Clinton, Roger Ebert and Richard Branson would tell you to read this book for your grandchildren. But what if you don’t plan on having grandchildren? If you don’t even like kids? Or just the idea of your kids having kids? Because the planet has changed, and we’re doomed if we don’t change too, McKibben would tell you that, if nothing else, you should read it for yourself. And, if it means anything to anyone, I agree.

Lily Hicks can be reached at [email protected].