NCAA baseball was introduced to aluminum bats before the 1974 college season. Since then, all schools across the three divisions use metal bats due to the trajectory of the ball and the way it favors the offensive aspect of the game.

It seemed like a match made in heaven for both schools and the players: schools loved the idea of saving money on bats that could not shatter, and hitters loved the idea of a larger sweet spot and the added power produced by metal.

After more than a decade without an inquiry by NCAA officials or any self-regulations imposed by top programs across the country, trickling down to D-III schools, the NCAA stepped in and enforced a lower limit on the weight of the bat before the 1986 season. The weight change, with its purpose to have a lighter bat that would decrease the impact on the ball, actually did the opposite, increasing as much as an estimated 10 percent. As the years went along and more changes were made to the designs of the metal bats, companies like Mizuno, Easton, Louisville Slugger along with others cashed in on the idea of mass producing aluminum bats that would support high fly balls traveling out of ballparks around the country.

Numbers throughout Division I baseball skyrocketed over a for the next ten year mark, which saw hitting statistics expand astronomically and pitcher’s earned run averages jump to new heights.

In 1998, the offensive outbursts became too noticeable for NCAA officials to not take action. The ’98 season saw old hitting records fall by the wayside. New records were set for batting average (.306), runs-per-game (14.2) and homeruns-per-game (2.1). Pitcher’s ERA’s jumped to an average of 6.12.

NCAA baseball needed to make a change and did, working with manufacturers to create a metal bat with a more wooden feel and less of a sweet spot. The science behind it would be dubbed the “Ball Exit Speed Ratio (otherwise known as “BESR”). The development of a new, denser bat proved to be successful, as numbers throughout the NCAA dropped over another ten-year period.

In 2008, however, offensive trends became apparent again, as numbers slowly increased over a three-year period. Batting averages rose from .296 to .302 between 2007 and 2009. Runs climbed by more than 1.5 per game in the same timeframe. The reason? The bats.

Like breaking in a new shoe, there’s a method behind breaking in a composite aluminum bat. With the carbon fibers and glue inside the metal reshaping and breaking up with more and more use, the bat’s performance improves over time, resulting in more flight on the ball.

So, with batting stats on the rise once again, the NCAA stepped in and facilitated a solution.

A new standard known as the Batted Ball Coefficient of Restitution (BBCOR) now measures the “bounciness” of the ball coming off of the bat after contact. When first designing the new standard, the goal was to create a bat that felt like wood, but acted like a metal bat.

Although the NCAA claims that the reason for the new regulations was to eliminate the risks of balls flying back at pitchers, corner infielders and even first and third-base coaches at alarming rates, fewer runs scored and an emphasis on pitching and defense would become the likely byproduct. Simply put, this new bat regulation, carefully calculated and not seemingly doomed to backfire like the composite method, will ultimately change the course of the game at the collegiate level for years to come.

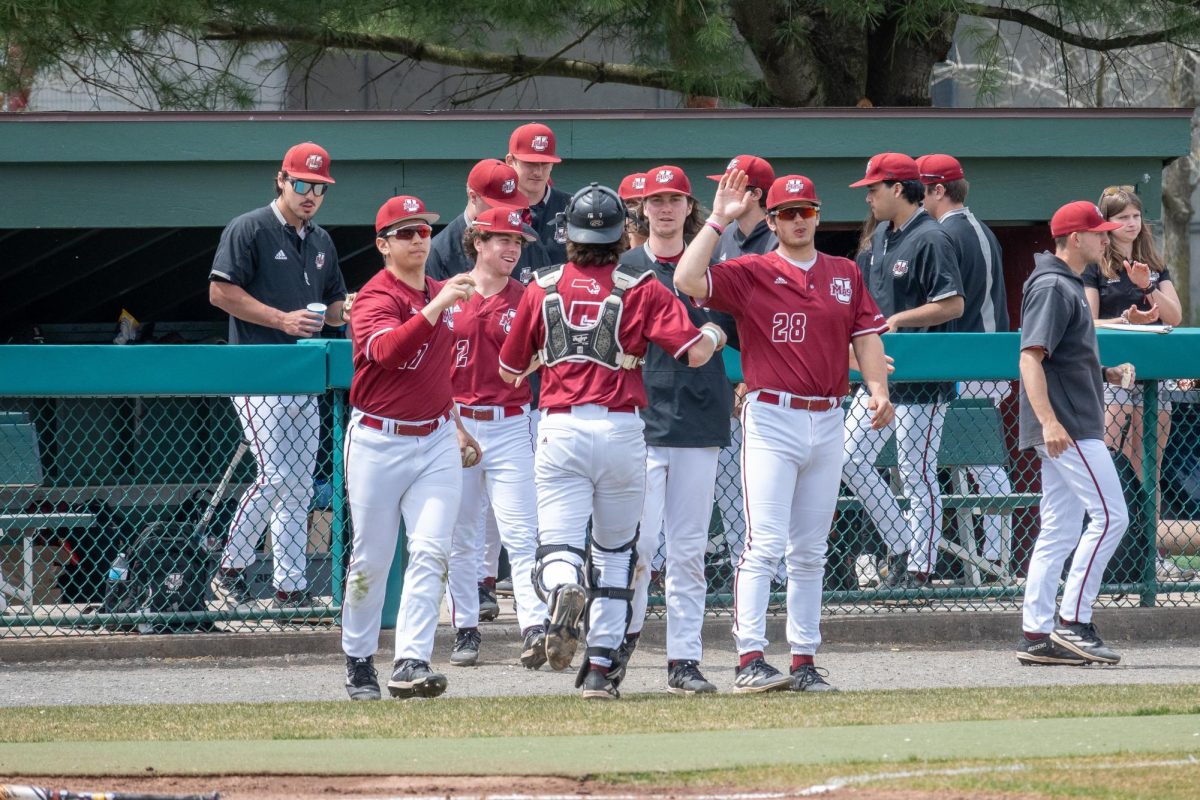

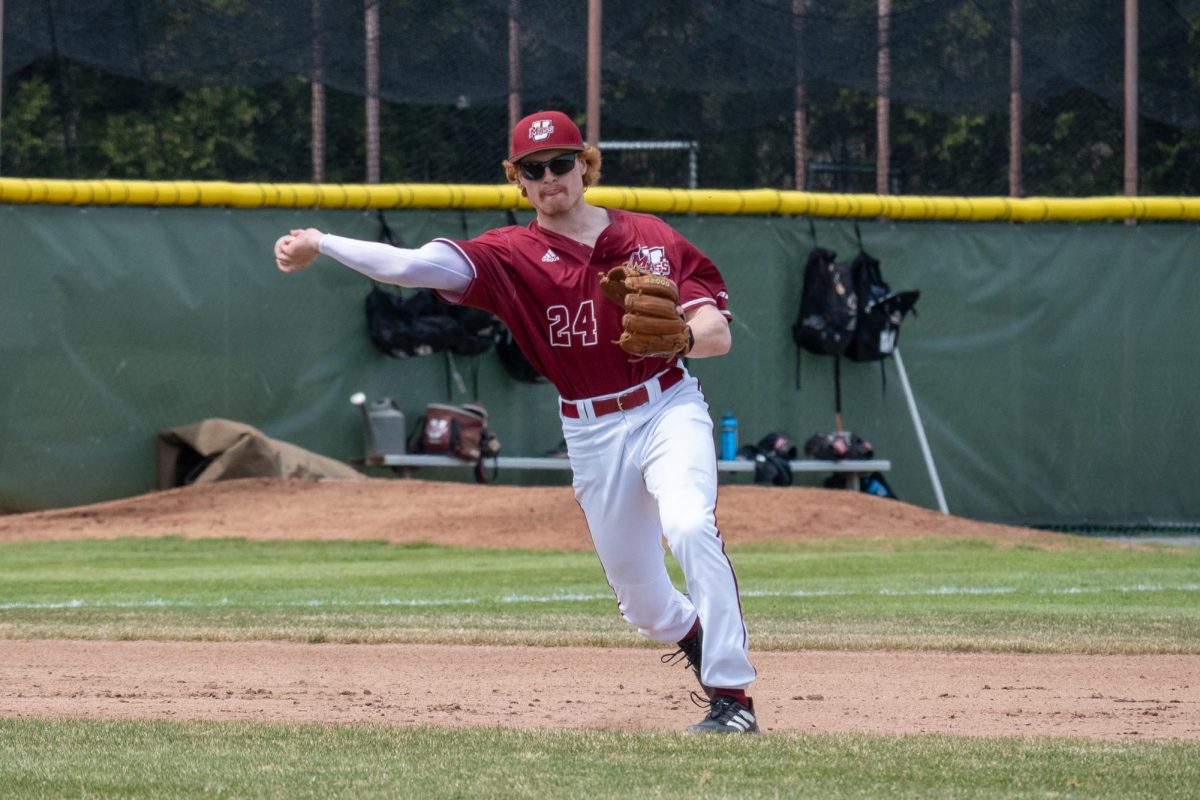

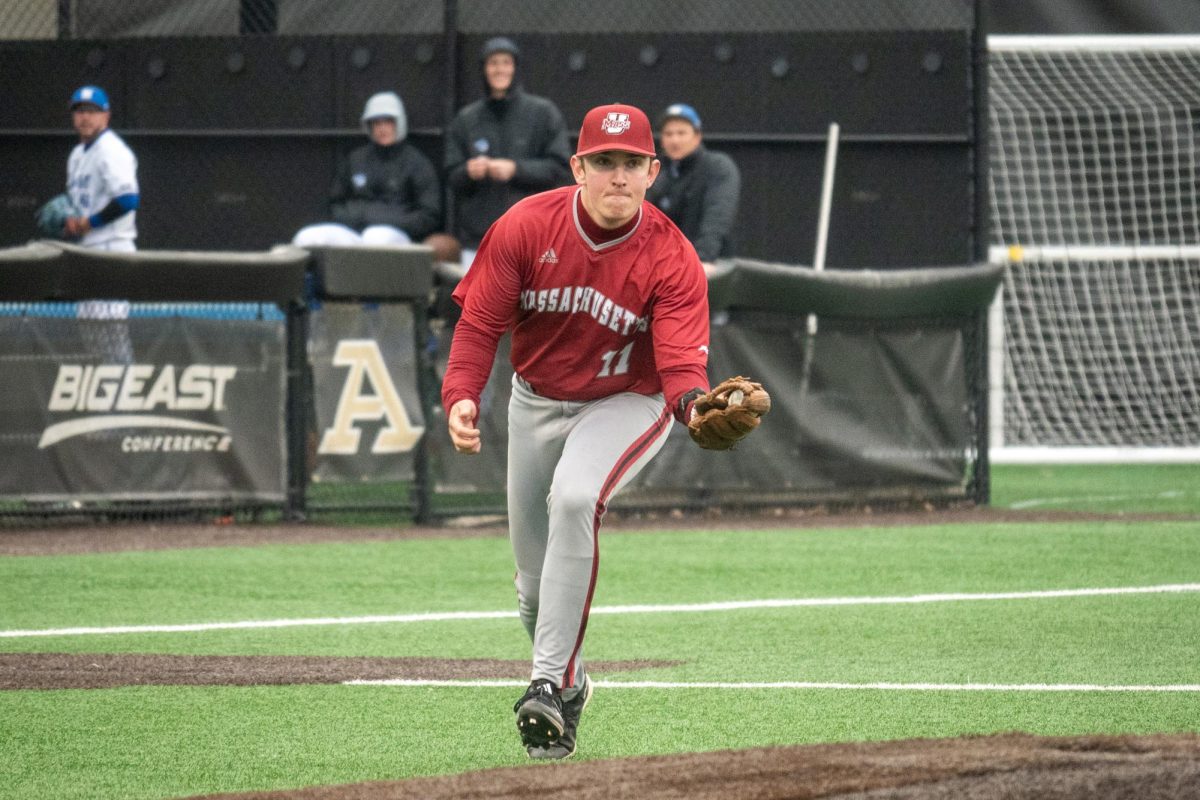

This idea of a slower ball in a pitcher-friendly ballpark may benefit the pitching staff for the Massachusetts baseball team, possibly changing the culture and identity of the team. It could put a stamp on a program that, for the last few years now, has had trouble when it comes to pitching.

UMass coach Mike Stone embraced the new bat regulations.

“We use wood bats in practice throughout the fall,” said Stone. “It teaches our players how to swing the bat correctly, and I feel it will really pay off for them with these new bats that have less pop.”

Stone was critical of the old methods and products hitters were using.

“I believe the performance bats really hurt the game,” said Stone. “There wasn’t as much emphasis on working on the fundamentals, because the guys were hitting the ball out left and right. With less balls going out, defense and pitching come more back into the picture.”

Senior captain Eric Fredette, a hitter in the middle of the lineup this year for the Minutemen, expressed that basic fundamentals at the plate still reign as the top priority – no matter the adjustment with a different bat.

“We’re definitely working on hitting more line drives in the cages and in practice,” said Fredette. “However, you still have to bring the same principle from before to the plate. When it comes down to it, you can’t change too much of your swing. Whether it’s using a wood bat, metal bat, or these new BBCOR bats, you can’t change your swing that much.”

Whether it’s still using basic fundamentals at the plate, or changing your game up entirely when it comes to hitting, many in the business of college baseball agree that a change in the style of the game is coming. Whether we see it immediately, next year, or somewhere down the line in the foreseeable future, a new bat will equal the game being played in a new way.

Other coaches around the country have expressed their views on the new regulations. Texas Christian head coach Jim Schlossnagle feels it’s a major impact, saying colleges, “will be playing a different game in the spring,” with more focus on defense and small ball. Schlossnagle went so far as to say that he believed that the bats used last year throughout the conference were “perfect,” and that changing regulations now would make the game more “professional-style,” compared to the unique style collegiate baseball provides the fans in that part of the country.

Although many coaches aren’t so bold as to say that the game will become more like the professional leagues, many agree with his meaning behind Schlossnagle’s words. Some parks play in favor of pitchers already, with deep outfields, wide gaps and plenty of area behind the foul lines for balls to be tracked down and caught.

Scott Cournoyer can be reached at [email protected].