Underneath the bed in her New York home, a notebook collects dust — not so much because of negligence, but instead because the ink that lies on the pages of the paper taught lessons that made Sarah Crowley who she is.Now, she keeps the notebook around and honors her growth by living the life that those ink filled pages told her she could.

An average Friday night for Crowley in high school was spent in the basement of a Long Island home, talking about boys, sports or various other teenager topics. A shy, anxious version of herself back then, Crowley never developed a strong interest in socializing beyond the hallways of school or the close-knit friend group she had. The idea of parties didn’t spark desire, and the idea of crushes turning into actual relationships seemed far out of reach.

Crowley’s athleticism and passion for sports put teammates in her life all throughout high school, but she found that her closest friends never played the same sport. After making the varsity lacrosse team for Harborfields High School as a freshman, her social circle expanded, but Crowley herself did not.

“It was a very hypersexualized group,” Crowley said.

The topics of sex, boys and relationships were at the forefront of most conversations, which only contributed to Crowley’s feelings of being the “odd ball out.” Instead of being nervous about a big game, a key matchup or a skilled player, Crowley was anxious about being asked about her first kiss, or about boys at all.

When new coach came in junior year of high school, she began to feel comfortable with a leader who understood all types of girls on the team. But even after capping off her high school career in a better environment than she first came into, the next steps felt like a journey in the wrong direction.

Crowley arrived on campus at the University of Virginia and quickly felt like there was a standard to meet. Socially, romantically, in the way people presented themselves, Crowley felt different. It didn’t take long to recognize it wasn’t her school, her environment, or her new home. So, she began looking for other schools.

Crowley scheduled a last-minute tour of the University of Massachusetts without talking with the lacrosse coaches, or meeting with any member of the athletic department.

Crowley says the first thing she noticed when she arrived on campus was the way people dressed.

Having just experienced a “girls in pearls, guys in ties,” tradition for athletic events on campus at UVA, the idea of freedom to wear different clothing caught Crowley by surprise. Crowley herself never felt like she had a relationship with her clothes, and never really felt confident in them. But the hodgepodge of Vineyard Vines jackets, pajama bottoms and Nike sweatshirts, flowy colorful pants, and tank tops that dressed the UMass student body appealed to her.

“The whole vibe that it gave me was that underdog feel,” Crowley said. “That is what I feel like, that is what I associate with, that is totally what Sarah is. They [UMass] embraced underdogs.”

UMass’ accepting vibe bled into Crowley’s personal life when she committed to the team. Arriving late, as a sophomore, she knew nobody. There were no athletes left to room with. But unlike previous experiences, people didn’t push her away because she didn’t look a certain way, and the random hellos from strangers while walking gave Crowley the confidence to make the most of the situation in front of her.

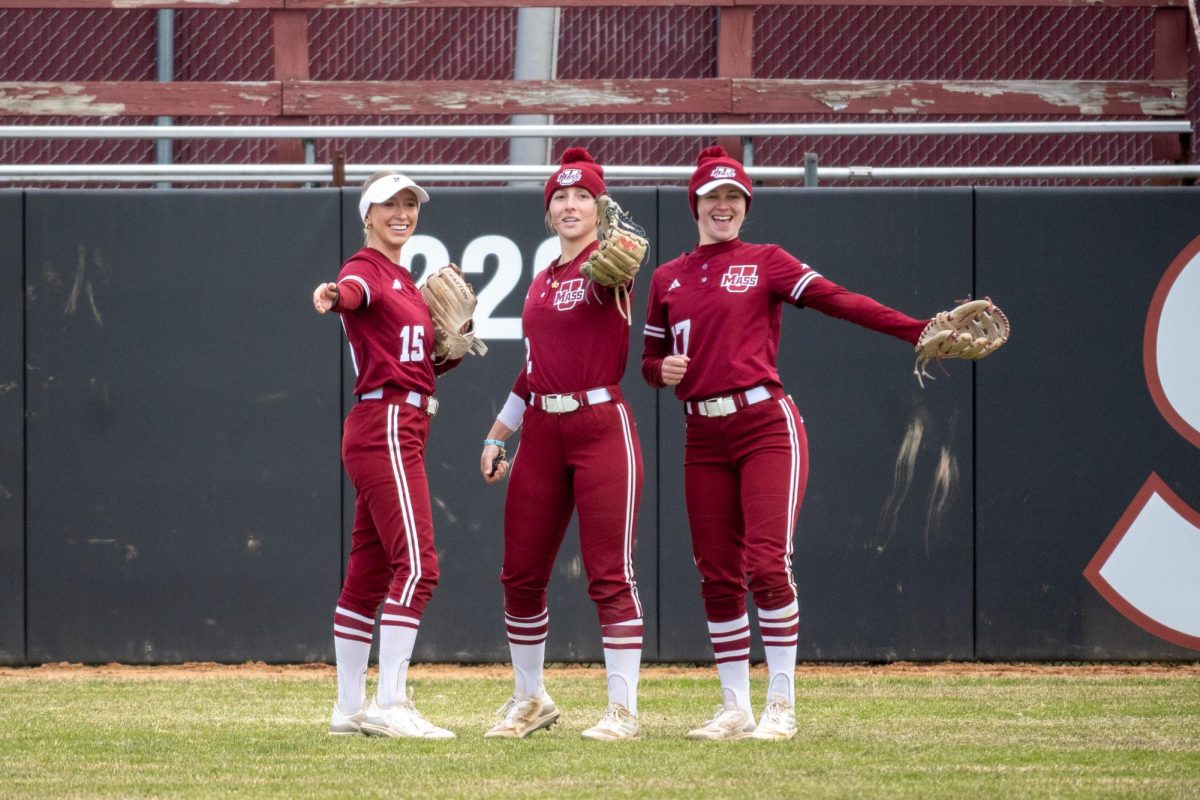

On the field, Crowley was dominant and provided a spark for the Minutewomen in her sophomore and junior years. She was a force who seemed to have it under control.

And by this point her life, Crowley had been in relationships. The insecurities she felt about how she dressed or how she looked began to feel more secure. But when senior year came along, lessons learned outside of Garber Field gave Crowley an entirely new perspective. This time it wasn’t one related to sports.

As she sat in Gender and Society, a class in the women’s studies department of UMass, Crowley listened. With zero expectations, Crowley became a sponge of knowledge and perspective. Based off the syllabus, she didn’t realize just how personally applicable the topics of conversation would become.

“How was I so blind to everything going on around me and inside of me,” Crowley said.

Growing up, the ex-boyfriends and male crushes had Crowley convinced she was solely attracted to men. The idea of anything different never took up space in her head. But the warm, accepting atmosphere on campus combined with her newfound perspective from her women’s studies course changed things.

It was a combination of that class, UMass’ climate and waking up one day realizing that she had romantic feelings for a teammate. She liked girls in that way, and they began a private relationship. The notebook she filled with notes from class stretched beyond the use for exam preparation. It became a guide to her own life, a safe space for understanding and written acceptance.

“I still have that notebook under my bed, because this literally changed my life,” Crowley said.

But as much as that class impacted Crowley’s life, she found herself revisiting old fears in a new place.

Hallways were never a place of comfort for Crowley. In high school, the harsh lights made it hard for Crowley to hide from those older teammates who looked for underclassmen to talk to. When reflecting on life in high school, memories of teammates playfully slapping her body resurfaced.

“I would think, ‘don’t do that to me,’ but I would laugh it off,” Crowley said.

In 2017, Crowley began the commute from her house to Boyden Gym. The locker room is hidden within a building that rests on a busy street on campus. The environment itself is a mix of private and public. The doors that require athletes and coaches to use an identification card to scan in secure the safety of who walks in, but the cars zooming, students roaming, and Amherst community members watching, running, walking, and living nearby publicize the space.

Following a text message from that previous night, Crowley once again dreaded seeing teammates in a hallway.

Crowley was outed accidently by a teammate in a group text thread and the months of long secret relationship with a fellow teammate was now public. It was like Crowley embodied the private and public atmosphere of Boyden.

“I didn’t have to face anyone until that morning in the locker room. Walking towards the locker room in Boyden, I wanted to cry and throw up.”

The uniform came on, she beelined to her locker and ignored everyone.

“When you are in that zone, you try to turn the switch and I think for an athlete it can be a good or bad thing,” Crowley said. “For me I was using it as a crutch in that situation because I could ignore everything else and be just a player.”

When her then girlfriend walked in shortly after, there was no more hiding it. But that was ok.

“At UMass, there wasn’t so much of a standard because the conversation was much more open,” she said. “Even though I still felt as though dating people of the same gender wasn’t talked about a lot, it wasn’t looked down upon.”

Crowley internalized everything from her past and thought that people wouldn’t accept her, so she kept her relationship a secret but was blown away by how normal it was to her teammates. Crowley knew her teammates never made homophobic jokes or implied that a same-sex relationship was wrong, but the idea of coming out was still daunting.

Riding on the wave of text message communication, Crowley took what she said as the easy way, and put her parents in yet another group thread. With a Mother’s Day event for the lacrosse team coming up, the realization that her teammates knew something her mother didn’t forced Crowley to share the news back home.

“We don’t care.” “We love you,” was the immediate response from her parents. Rainbow emojis and hearts to follow.

“If that weekend wasn’t coming up, I don’t know if I would have told them for a while,” Crowley said. “It was just so situational. I don’t regret telling them, but I regret telling them in the way that I did.”

—

Roughly 30 years prior to Crowley’s arrival on campus, a different roster of Minutewomen took to Garber Field in a maroon and white jersey for the same reasons players do now. On the team, there was even another Long Island native, Christie O’Connor. But the conversations about same-sex couples were non-existent. A coming out story via text message was far from possible.

Back then, the women’s lacrosse team practiced close to the softball team. O’Connor could look over and glance at fellow UMass athletes. Athletes were taught to only focus on the sport, and rarely bring boys or outside romantic distractions into conversation. Boys. It was only boys. So, when two women on the softball team began a public relationship, it caught the eye of those around them.

“I was so intrigued because I just thought ‘how brave of them’,” O’Connor said. “It was just something people didn’t feel comfortable doing but they did. I thought that was so incredibly brave.”

There were no rainbow flags draped across campus like you could find now or mention of dating girls in conversations in the locker rooms. O’Connor and the rest of her lacrosse team had a similar “we don’t care, it is ok” form of acceptance.

“They were way before their time for sure,” O’Connor said. “I think people hid it because they didn’t feel like they were supported.”

Crowley knows that she was not the first sexually fluid person on the women’s lacrosse team at UMass but recognizes she might have been one of the first that was able to say it.

Crowley stuck around after graduation and watched a wave of teammates come out. Maybe it was seeing Crowley as a senior leadership figure that made underclassmen feel comfortable, but looking back, she says she felt like a rainbow volcano erupted.

“I had a front row seat to how growth happened after I left.”

For the hodgepodge of students that make up the UMass student body, light and darkness contrast through individual experiences. The metaphoric tunnel is reached through various ways, for a variety of reasons. A diploma and a goodbye to campus may be a dreadful tearful shed or a sigh, with weight lifted off shoulders. UMass meant something special to Crowley.

“It was like a beacon of light; some people might think that is dramatic but to me that is exactly what it felt like,” Crowley said.

Sometimes culture doesn’t need a universal definition, and instead can be individualized.

“The culture in general just made me feel welcome. I still tell people today, ‘consider UMass’.”

Lulu Kesin can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @Lulukesin.

Judy Faherty • Jun 30, 2021 at 1:44 pm

Beautifully written story about this young woman’s journey towards allowing herself to bevome her true self. Loved the contrast with the earlier alumnus’ experience and how welcoming and accepting UMass is to all. The world could learn a lot rom these students!