Joe Ledoux climbed out of his father’s car, waved a brief goodbye and breathed in the fresh air of the Berkshire mountains. The 29-year-old magician adjusted his scarf and walked up the base of the off-season YMCA campground.

“Did you drive here? You have to be very careful when you drive home,” said pagans wearing robes with belled sleeves who stared at Ledoux, looking genuinely worried. Unsure what they meant, Ledoux informed them that he’d been given a ride by his dad.

“Oh good! You planned it well.” The pagans said, noticeably relieved. Still confused, Ledoux went to the campsite with his new companions and wondered what was in store for the evening. Already, the sky was darkening and preparations were underway for evening rituals.

For a magician, Ledoux wasn’t feeling very magical. Years of doing tricks for small audiences whittled down Ledoux’s magic into a sliver of what it once was. His faith was buried under the pressure to give dopamine-starved crowds a quick hit of another reality before they came down and stumbled to another source. Desperate to revive his dying magic, Ledoux went to Grandmaster of Magic Jeff McBride, his mentor. McBride had the perfect solution: Ledoux was to attend the next Twilight Covening, explained by Ledoux as a place of magical ecstasy, but also “a pagan gathering in the middle of the woods.”

At the Covening, Ledoux was given a choice of which clan he wanted to join for his time in the mountains. He chose to study with the shamans, or spiritualists who could access other dimensions. Shamans, Ledoux thought, were the original magicians, artists and scientists. They had faith and knowledge of the natural world and could reach across realities to paint fantastical scenes for their followers. Enticed by the thought of leaving his current reality and accessing a fourth dimension, Ledoux was welcomed into the clan of realm walkers. In the evening, Ledoux joined the leading shaman in a ritual tent. The shaman dressed in plain clothes, but there was a magic spark in his eyes. It was as if he was asleep Ledoux’s reality, but active in another. Ledoux admired the serenity and joined the circle.

“Someone is coming,” the shaman spoke plainly, as if observing that the grass is green. Ledoux strained his ears but did not hear anyone approaching the tent. Seconds felt like minutes until the shaman’s prophecy came true. Footsteps crunched in the dirt and another ritualist joined the tent. Impressed, Ledoux allowed himself to be guided as a meditation began. The sweet, earthy smell of burning sage filled the air, its smoke swirling wildly in the dim candlelight. Somewhere, a rawhide drum beat steadily, the confident booms lulling Ledoux into a trance.

“Imagine a hole in the Earth, a gateway,” urged the voice of a shaman. Ledoux allowed his focus to drift, and he fell headfirst into the fourth dimension.

*************************************************

Aristotle was among the first to theorize about the number of dimensions in our world. His first book “Heaven,” which was written in 350 B.C., states: “The line has magnitude in one way, the plane in two ways and the solid in three ways, and beyond these there is no other magnitude because the three are all.” By 300 A.D., ancient mathematicians studying algebra discovered powers for variables beyond three, which perplexed many as they were seen as unreal possibilities. As math progressed into the 15th and 16th centuries, powers beyond three were considered in equations, but were still viewed as not of the natural world. Then, in the 18th century, an idea was popularized that time is the fourth dimension — a notion that is kind of correct (more on this later). Finally in the late-19th century, mathematicians studying higher dimensional geometry gained momentum and published theories about how to conceptualize a fourth dimension.

Today, mathematicians and scientists have widely accepted theories about higher dimensions and have started attempting to visualize possibilities beyond our spatial three. Mathematically, there’s freedom to work in any number of powers up to infinity, but our physical world is restrained in the prison of a cube. If Aristotle were to find himself inside of a cube, he could take a few steps forward, a few steps to the right and jump in the air. Here, Aristotle would have utilized all three spatial dimensions and arrived at the conclusion that there could not be more: he could only see three.

Tom Banchoff is one of the top mathematicians working to visualize the dimensions that early scientists once called unnatural. A renowned professor at Brown University and pioneer of fourth dimensional modeling, Banchoff was originally inspired to see in 4D at age 10 after reading a Captain Marvel comic book. In a futuristic laboratory, Banchoff recalls that scientists “were working on the seventh, eighth and ninth dimensions,” which prompted a young reporter in the comic to comment, “I wonder what happened to the fourth, fifth and sixth dimensions?”

In 1967, Banchoff began teaching at Brown, where he pursued a deeper knowledge of the fourth dimension. By 1975, he created several animations with colleague Charles Strauss that displayed a hypercube rotating in four-dimensional space. Their work culminated in an award-winning film and led to an interview with The Washington Post, which was printed alongside an image by the famous Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dali.

Soon after the article came out, Banchoff got a note from a woman representing Dali. He was initially worried that he was facing legal trouble because The Post did not have the rights to republish “Corpus Hypercubus.” He grew even more worried when the woman asked Banchoff and Strauss to travel to New York City to meet with Dali, but Strauss was optimistic, telling him “It’s either a hoax or a lawsuit, but the worst we can get out of it is a good story.”

When the pair strolled into the cocktail lounge of the St. Regis Hotel, Dali was waiting eagerly to meet them, pointy mustache and all. As it turns out, Dali was fascinated by Banchoff’s complex geometry and wished to apply it to his art. You don’t arrive at the fourth dimension by working within the confines of standard geometry; you have to get a little weird with it. And if there was one three-dimensional denier that wanted to get weird, it was Dali.

In Dali’s painting, “Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus),” Christ is displayed as a martyr on the unfolded net of a hypercube instead of the traditional cross. Art historians have a field day with this piece, but a common interpretation is that the geometric fourth dimension is the same dimension that Christians believe contains God. Visualizing a hypercube does not let you see God, but it does let you see the fourth dimension, which Dali argues is close enough.

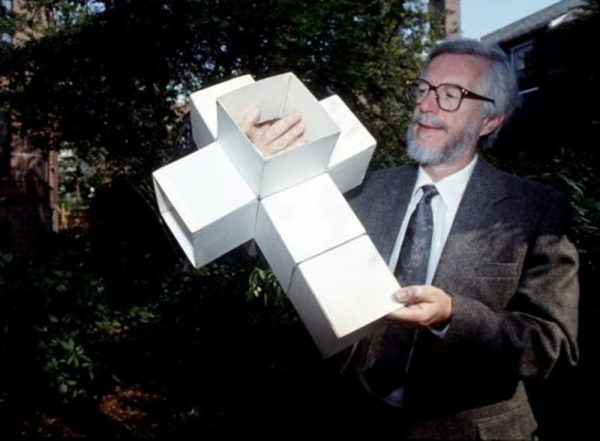

When Banchoff showed Dali his folding hypercube model, the same model that he used in his painting, the artist simply stated, “I may have this,” and put the model in his museum in Catalonia. Banchoff took this as a sign of his approval, and the pair continued to meet and discuss art and geometry until Dali painted his final major work in 1983. “I’ve met a lot of interesting people — mathematicians are famously interesting — but Dali was something else,” Banchoff said, smiling as he remembered the fond times. Dali’s inspiration still lives within Banchoff today, as he started taking painting classes at the Providence Art Club. Even to the mathematician, the fourth dimension is more than just tricky geometry.

*************************************************

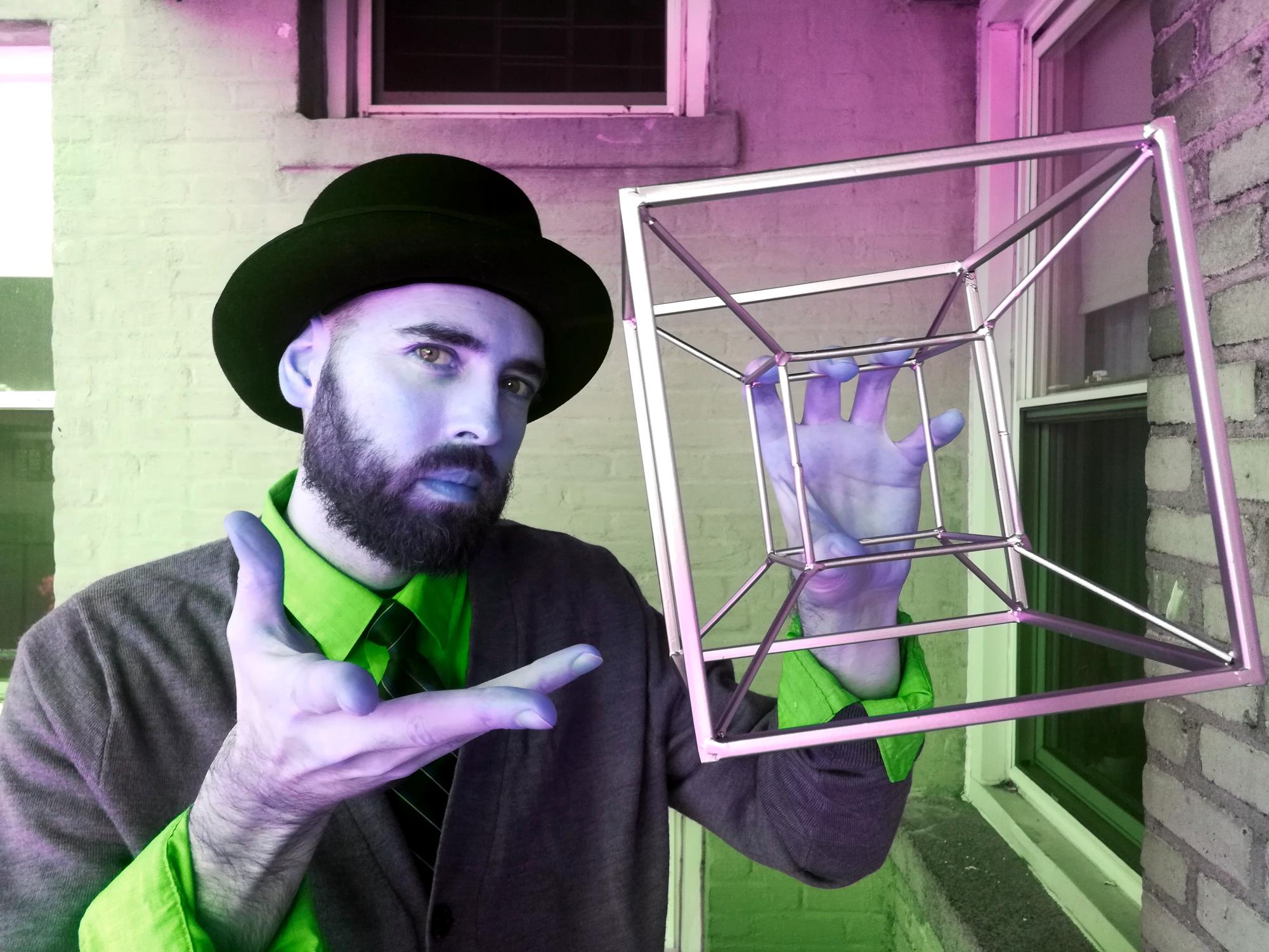

Just under 40 years later, another artist reached out to Banchoff. This time, the artist wasn’t very famous and Banchoff didn’t need to worry about a lawsuit. Rather than looking for inspiration, the artist was looking for approval. Inspired by his time with the shamans, Ledoux became obsessed with the fourth dimension and crafted his own theory on how to visualize what was supossedly impossible to see. Even though Ledoux was a part-time magician/artist/animator/skateboarder/shaman, he went straight to the top mathematician in his field with his theory. With an admiration for the magical side of the fourth dimension, Banchoff investigated Ledoux’s ideas and found them credible.

“It’s not a trick, it’s another view of things,” Banchoff said about Ledoux’s work, adding that Ledoux’s model is a mathematically sound, clever way to view a four-dimensional object. To Ledoux, the approval was invigorating. “It meant a lot just to find out my idea was solid,” Ledoux said. Many would struggle with the courage to cold call the world’s preeminent authority in a field they had no background in, but those closest to Ledoux know that you can’t resist his genuine, magical charm.

“When [Ledoux] was younger, he asked every single girl he was into on a date. It was extremely painful,” said Matthew Dinaro, one of Ledoux’s lifelong friends. While many men would give up after a few tragic rejections, Ledoux forced himself to endure the pain and pursued what he wanted with a sincere, unyielding force.

“There’s a restlessness about his whole pursuit,” Dinaro remarked about how Ledoux had a unique talent for capturing the attention of people that likely had more pressing matters than speaking with a magician. Dinaro himself was captivated by Ledoux when they first met as coworkers over a decade ago. Both Ledoux and Dinaro were gallery guards at the Isabella Gardener Museum in Boston. While a magician and a poet may not be the typical crime-fighting security duo, Ledoux enjoyed the rich history of the art and found the serenity of the museum to stimulate his creativity.

“We were both into a lot of weird s**t,” Dinaro laughed. He and Ledoux would constantly get in trouble with their bosses for shuffling tarot cards, practicing magic tricks and talking about real warlocks living in America instead of doing any guarding. In fact, Ledoux hated the part of his job where he had to actually protect the artwork. Ledoux isn’t the kind of guy to yell at you for getting too close to an exhibit. Instead, he’s the type to gently misdirect you away with a story about a nearby painting and puzzle you with a philosophical quote, such as, “Whatever borders on the unknown gives the world its mystery.”

He isn’t the type of magician to trick and deceive; he’s a “purest,” according to his personal mentor McBride. Ledoux’s magic is subtle, magnetic and “radiates a spiritual sensibility,” serving as a refreshing break from the “showmanship” of the modern era of magic. But above all else, Ledoux isn’t the type of person who meddles with the mundane. Ledoux meddles only with magic, and while some may doubt a shaman’s geometric theory, he may have gotten humanity one step closer to seeing the fourth dimension.

*************************************************

To anybody that isn’t either a renowned mathematician, the world’s greatest surrealist or Ledoux, trying to visualize the fourth dimension can make your brain hurt — but once you push through, you’ll see something otherworldly.

Banchoff approached his visualization by making an unfolded hypercube, which is a cube in the fourth dimension that is analogous to a cube in the third dimension. If you were to unfold a three-dimensional cube into its six sides, the result would be a net that looks like a holy cross. By refolding these two-dimensional squares together, you take a two-dimensional shape and add a dimension to it, forming a three-dimensional cube. If a two-dimensional net can represent a three-dimensional cube, then a three-dimensional net can represent a four-dimensional cube.

Banchoff created a net of eight three-dimensional cubes that would create a hypercube if it were physically possible to fold the net together. This was the same model that Dali painted in “Corpus Hypercubus” and the same model that the surrealist permanently borrowed from Banchoff to put in his museum.

Although it is confusing to imagine how this model folds together, all that matters is that a net of cubes is a three-dimensional representation of the fourth dimension, just as a net of squares is a two-dimensional representation of the third dimension.

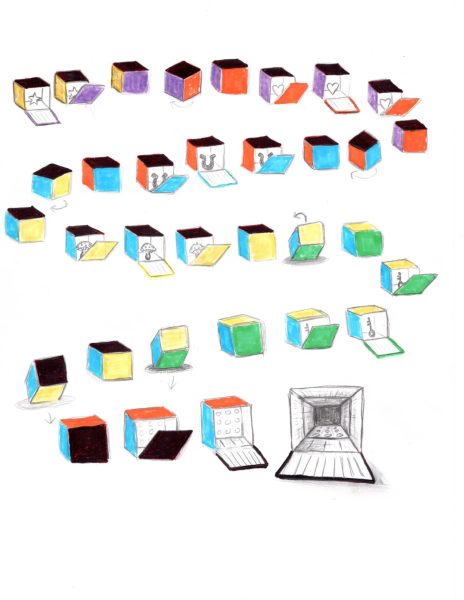

While Banchoff’s work is legendary, Ledoux’s theory is actually much easier to visualize. Ledoux’s theory came from the realization that the eight cubes in the unfolded hypercube can be viewed as a series of folding doors, which is why he calls his invention the “hyper-door theory.” The idea is that you open different squares of a cube like doors, see a different shape inside and rotate the cube to continue the process. Using the diagram below, Ledoux explains how to see the unseeable:

“You see a star inside the cube. Close the purple door and rotate the cube to the left, so the orange door is in front. Open the orange door and you see a heart inside. Close the orange door and rotate the cube to the left so the blue door is in front. Open the blue door and you’ll see a horseshoe inside. Continue this process of opening and flipping until you’ve reached the key.

“Close the green door, then flip the cube so the yellow door is in front again. Flip the cube once more, so the black door is now in the front. Open the black door to see a rear wall covered with spots. Push in the rear spotted wall and it will fall forward to the floor, revealing what we call ‘the center cube’ — it’s in the distance, and is the exact same size as the whole of the colored cube.”

While the model looks like simple boxes, you just saw the fourth dimension. In summary: Banchoff’s unfolded mode has eight cubes that make up the hypercube net. In Ledoux’s model, the same eight cubes exist, but are presented in a different way.

The six colored doors in Ledoux’s model all represent an individual cube; imagine each door opening as a new, individual cube. The “center cube” in Ledoux’s theory is analogous to the middle cube of Banchoff’s model. By knocking down the spotted door in Ledoux’s model, it is as if we are looking through a cube of the hypercube net into the center cube. Finally, the colored cube itself is a cube, which adds up to the same eight cubes used in Banchoff’s model.

The genius of Ledoux’s theory is that it doesn’t require mind distortion to imagine complex geometry. Everything within the theory works within three-dimensional cubes. The theory would be better made into a video with stop-motion, where a camera can start and pause at specific locations to show the different items. The manipulation of the camera would therefore be the fourth dimension that the cube is being “folded” by. In other words, time is folding the cube and the camera allows Ledoux to start and stop time to allow for a hypercube visualization.

*************************************************

Back in August 2020, before Ledoux contacted Banchoff, he won modest interest for his theory from fellow magicians. He even published an article in Vanish Magazine, a magic magazine for an audience of otherworldly fanatics. McBride was particularly impressed, proclaiming that Ledoux is “capturing lightning in a bottle.” But Ledoux wasn’t satisfied with the approval of magicians. He wanted to go straight to the top and get his work published in a scientific journal. With the help of mathematicians, he could develop the first ever video that showed a hypercube without distortion. And who better to work on his idea than the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Ledoux opened his eight-minute long video to MIT with a magic trick: procuring a coin from seemingly nowhere while dressed in a sharp blazer jacket and purple fedora. He outlined his “hyper-door” theory and claimed that “it would be a new breakthrough for theoretical physics.” Ledoux thought that with the technology and personnel that MIT has access to, it could create the first professional film of a hypercube without distortion. He ended his video as himself, an honest scholar: “I’m not looking for money, maybe just a credit with my name. I’m not looking for fame.”

MIT responded to the video, calling the idea “interesting.” However, it also said that it was a research institute, and Ledoux had already done all the research. It was certainly one of the kinder rejections Ledoux could have received, but it was still a rejection. “I’m losing sleep, I want to know if it holds value,” Ledoux said, with all hopes of an MIT partnership dashed. The theory is still unpublished in the scientific community. It lives in the pages of a magic magazine and the minds of a few interested scholars. It is only a theory and a few pencil-sketched diagrams waiting to be loved.

*************************************************

After facing rejection by women in his youth with strength and resolve, Ledoux found himself a girlfriend. Ashley Rine develops IT for tech startups and is a self-described logical, technically-oriented skeptic. A surprising match for the philosophical shaman/magician. There must have been something magical in the air when the pair met in a Boston bar in 2006; they charmed each other and have been together for 16 years.

By 2013, Rine supported Ledoux but didn’t fully believe in his magic. However, when Ledoux cast a spell over the city of Boston that would make its citizens see fairies, aliens and sea serpents, she saw a glimpse of her boyfriend’s magic. After Ledoux cast the spell, Rine set up a website for people to report any sightings. The magician dusted off his hands and watched the spell captivate the imaginations of local Bostonians.

It kind of worked. There were some reports of fairies and serpents, but there wasn’t anything monumental. Perhaps the spell had some sort of proximity requirement, as the most affected subject was the one closest to Joe and the one analyzing all the website submissions.

Rine and Ledoux were in a park sometime after the imagination-bending spell having a picnic on a pleasant day. Perhaps she just had magic on her mind, but Rine witnessed a fairy fly by the park; a tiny creature with thin wings and pointed arms and legs. While she later rationalized that it was a dragonfly, her senses deceived her and magic was victorious.

“There’s more wonder in my day,” Rine said, describing her life with Ledoux. While still a logical thinker, she can’t help but let Ledoux’s wild imagination pull her along “like a current.”

Ledoux already accomplished the seemingly impossible: he helped his skeptical, logic-driven partner see mythological creatures. Now all he has to do is publish his theory about the fourth dimension.

*************************************************

Ledoux continued his story about his time with the pagans, giving credit to the experience for reviving his dying magic.

Ledoux and his fellow shamans-to-be were blindfolded and led into the middle of the woods. There was nothing but the dark, empty sky and his trust in complete strangers to protect him on his journey.

The group stopped at a bonfire and had their blindfolds removed. Ahead of them was an illuminated path to another fire, with a pagan dressed in a ritual phoenix garment waiting beside it. Its red, orange and yellow feathers mirrored the crackling flames, brightly illuminating in the darkness of the night. The phoenix explained the process of rebirth that they were about to embark on and sent the group to the next fire.

“Here you have to make a sacrifice,” the pagan spoke plainly, gesturing to a ritual blade. Ledoux looked around nervously and saw a fellow shaman cut a swath of their hair in one quick motion, tossing the sacrifice into the fire.

“I have a shaved head, I don’t have anything to cut, what am I gonna throw in this thing?” Ledoux thought to himself, eyeing the blade. He nervously grabbed the blade, cut a piece out of his treasured scarf, and hoped his sacrifice was good enough.

For the ability to visualize God, it probably was.

Luke Ruud can be reached at [email protected].