In small towns across the United States, students line up with five-dollar bills clutched in their hands, hoping that they got there early enough to get a front row seat in the student section. Cheese pizza, soda, loaded nachos, Friday night lights and the star quarterback embracing the cheer team captain after the game. It’s classic Americana.

But it’s not. Not anymore, anyways. And for a lot of people in this country, it never was.

Around 7.2 percent of people in the continental United States identify themselves as being a member of the LGBTQ+ community, which is around 24,150,000 people total. And with just 27 percent of LGBTQ+ children engaging in organized sports at either their middle or high school, and an even smaller percentage of those athletes going on to play at the Division I level in the NCAA, representation for LGBTQ+ youth is hard to find.

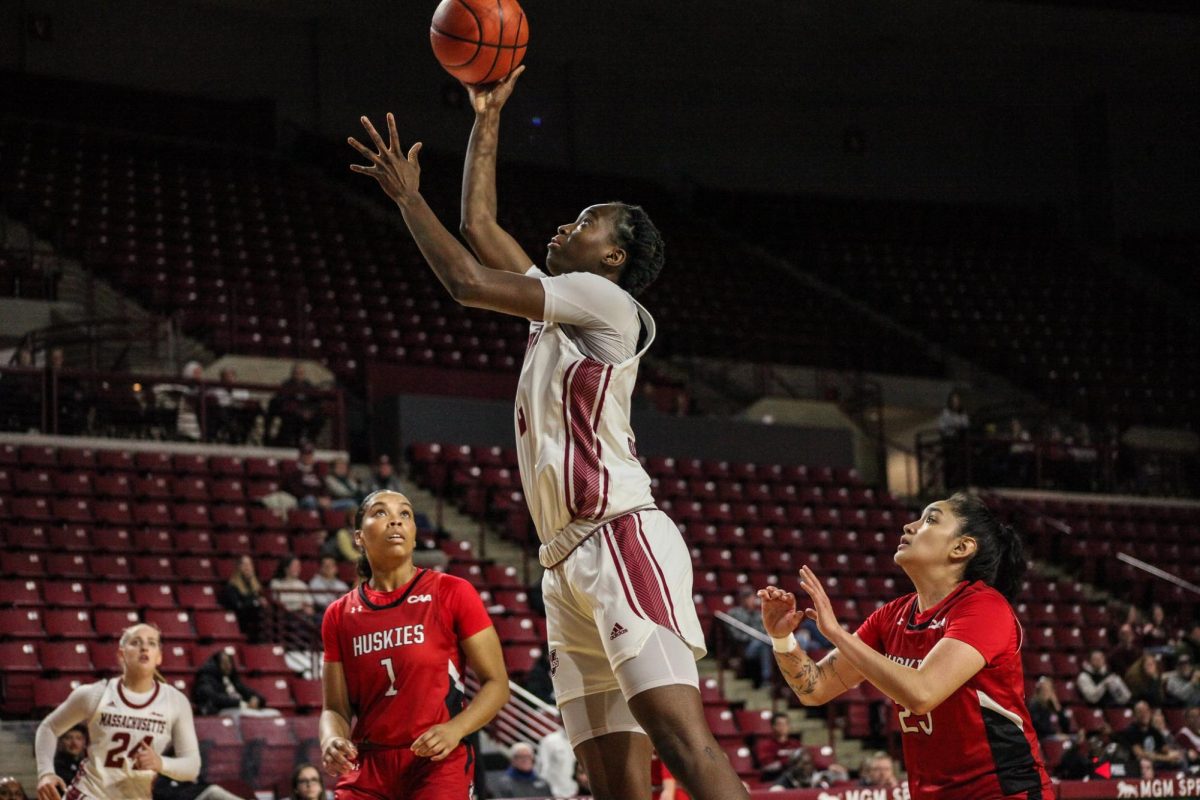

“Being queer kind of puts you in a different light, you feel like you stand out more, but in a different way [than the other talented athletes],” Lilly Ferguson, a sophomore and member of the Massachusetts women’s basketball team said. “That was one of the more challenging things for me, especially as I came to terms with my identity and the ways I wanted to express myself … it puts you in a spotlight.”

Many queer athletes fear ridicule if they were to come out while playing their respective sport. A study from Out on the Fields found that among both queer athletes and straight athletes, 80 percent of respondents said that they experienced or saw homophobia on their respective field/court. In that same study, 73 percent of lesbian, gay or bisexual currently out athletes believe that sport is still not a safe environment for LGBTQ+ athletes to come out in.

In one of the last sections of that study, 54 percent of cisgendered, straight male athletes admitted to using homophobic slurs within the past two weeks or hearing a teammate use homophobic slurs. As someone who spent much of their high school life heavily involved in school athletics, words like the f-slur and others were quite commonplace.

So common that a high school baseball coach had to sit his team down before practice and explain to the group of 14-year-old boys that saying gay, queer or even worse things could really hurt certain people. My coach. My team. Regrettably, my words. When words with that gravitas are used so nonchalantly, slipping in and out of everyday conversation, that almost hurts young queer athletes more than hearing them used in an abusive and aggressive context. When they hear these hateful words and slurs day in and day out, it reinforces the idea in their mind that they will face an overwhelmingly negative response, forcing them to remain in the closet.

“There’s a lot of people, especially younger people or people who don’t have people around them who support them … it’s important that us, athletes, [be] people that others look up to,” Ferguson said. “[We’re] able to put things like that on a platform and show that it’s okay to be who you are, it’s okay to be queer and it’s okay to express yourself in any way that you want to.”

That study from Out on the Field focused primarily on middle and high school athletes. In another study done by OutSports, just over 95 percent of queer college athletes surveyed that have come out to their teammates rated their experience anywhere from neutral to perfect. Conversely, just 4.6 percent of those surveyed rated their experiences as bad or worse.

As athletes continue to rise the ranks to higher levels of competition, teammates appreciate the work that it took each and every one of them to rise to a level of play that less than 10 percent of high school athletes reach.

“It’s hard, especially when you’re younger, when someone on the other team is misgendering you … making fun of you, like they know [I’m] a girl,” Ferguson said. “In college, it has become more accepted. Now, I see more people that look like me, not only in the UMass community but in other colleges, on social media … in high school, it really wasn’t that way.”

In a sports world that is still dominated by voices of the yesteryear, athletes face pressure to conform to how society believes that they should look, act and feel, regardless of the athlete’s actual sentiments. Representation for queer young people, not just in athletics, but across every facet of society, will only make it easier for the youth of today and the future to feel confident enough in their own identity to share it with the world.

“Be confident in who you are,” Ferguson said. “Even if you might not be exactly the same as the stereotypical [way] society wants you to be. Take pride in who you are.”

“You’re human. You matter.”

Johnny Depin can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @Jdepin101.