Among many factors that determine an individual’s access to healthcare, the language of medicine stresses a fundamental distinction between communication and transaction. To access healthcare is to interact with policy, and the larger systems that shape individual health outcomes.

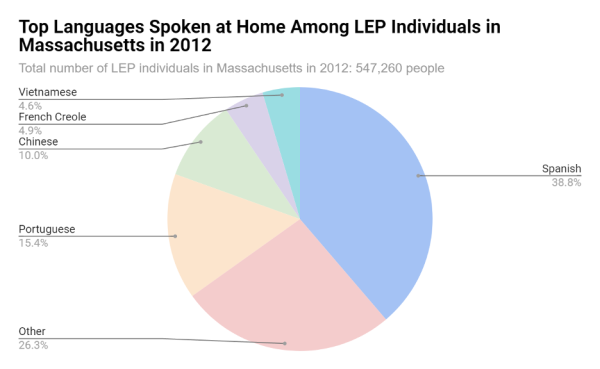

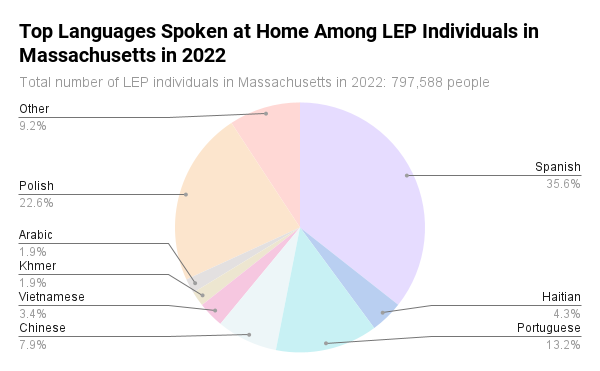

In the United States, more than 25 million people identify as having limited English proficiency (LEP). Limited English-speaking individuals compose more than nine percent of the adult population in Massachusetts.

The linguistic barriers such communities face is one cause for disproportionately poor health outcomes—reflected in higher rates of misdiagnosis and low health literacy.

Massachusetts hospitals are required by state and federal law to provide free aids and services to people with disabilities, as well as people whose primary language is not English. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, patients with LEP are entitled to medical interpretation and/or document translation services in any healthcare or emergency room facility.

At Cooley Dickinson Hospital in Northampton, Massachusetts, medical interpretation services are provided by trained professionals who help to facilitate communication between patient and healthcare provider in every aspect of their treatment.

Cooley Dickinson patients can request more than 170 languages. Among some of the most-accessed languages are Spanish, Chinese, Khmer, Arabic and Russian. Currently, there are five Spanish interpreters and one Chinese interpreter on staff at the hospital. Prior to the pandemic, the hospital had a Cambodian interpreter on staff as well.

Language interpretation services at Cooley Dickinson are also offered through remote and phone mediums. For deaf or hard-of-hearing patients, American Sign Language (ASL) is available, in addition to Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART) services which provide oral, tactile and close vision interpreting.

Wisinley Miranda-Leon, a staff interpreter for Spanish, said most patients that request services speak Spanish. Languages that Cooley Dickinson is not able to provide in-house interpretation for, including ASL, are sub-contracted through various agencies, via Mass Interpreters.

“We’re always accommodating to every single patient,” Miranda-Leon said. “We want to be able to help all the patients that we can — to be able to assist and provide the best care that they can have.”

In-person services are derived from Language Bridge LLC and Bay State Interpreters among others. Video interpretation is provided through AMN Healthcare Language Services, and phone services are provided through Language Line.

Emma Aldana created the Interpreter Services Department at Cooley Dickinson 15 years ago. In her role as the manager of the department, she oversees department operations and coordinates schedules for sub-contracted interpreters to work alongside those on staff.

At the beginning of the program, Aldana explained that they used phones to provide interpretation services, but this method posed a few restrictions.

“With the phone, you lack the opportunity of body language, which is important when you’re having a conversation with someone,” she said. “It becomes really hard, especially if you have people that are older patients and they don’t hear well… there are many complications that could go into this.”

Since the inception of the department, Aldana recognized that a phone call can only do so much. In 2019, the hospital implemented video remote interpretation services (VRI) to assist the department.

Through VRI, patients can receive more access to interpreters, especially during nights and on weekends.

“It’s a vital portion of the care to team up with an interpreter or to have an interpreter be part of the treatment team,” Aldana said. “[The patient is] clear on what they are saying to providers [and] the full message or the full information that’s given them.”

A look into the certification process for medical interpreters

The requirements to become a medical interpreter at Cooley Dickinson are defined by its parent system, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Trained medical interpreters can work in staff or freelance positions at MGH facilities or affiliate sites such as Cooley Dickinson.

Several programs exist in Massachusetts and across the country to provide baseline certification for entry-level medical interpreter jobs. Approved programs are offered both in-person and online from community colleges and independent training groups.

These programs typically require a minimum of 40 hours to receive a certification. Aldana said that medical interpreters at Cooley Dickinson are required to complete at least 60 hours of training. Pursuing a national certification, while not required to work at Cooley Dickinson, can be attained through one of two boards.

Hsiao-Yen Liu, the sole Mandarin Chinese-trained interpreter at Cooley Dickinson, completed a program from the Certification Commission for Healthcare Interpreters in 2013. Prior to this, Liu said she worked in another hospital for 15 years.

“During [those] 15 years, we learned every day and we went to a lot of trainings and a lot of different kinds of conferences so we had enough experience to take the [certification] test,” Liu said.

From certification to hospital application

According to Aldana, this training comprises instruction on medical ethics, terminology, standards of practice and exercises on patient-provider interactions. Though sample scenarios are heavily practiced in preparation, a medical interpreter’s true training starts once they are working in the field.

“In reality, 60 hours is just like the beginning, because once someone takes that training, they will be learning for the rest of their lives as an interpreter,” said Aldana. “They will encounter different situations and different things.”

Spanish interpreter Armando Verea took a non-linear path into the field. After working as a teacher in a bilingual program as well as with the state of Connecticut, Verea became a medical interpreter in 2012 at Cooley Dickinson — where he has worked ever since.

Verea’s background amplifies similar stories amongst his colleagues who shifted their careers in search of a more meaningful opportunity to help people.

“Every day you come up upon circumstances, situations that are logistical, emotional, practical, that you have to deal with…and it’s hard sometimes, but you gotta love what you’re doing,” Verea said.

What Verea shares also captures the influence medical interpreters have on patients with LEP, and specifically, these patients’ experiences in the healthcare system. Providing interpretation services, as Verea says, is ultimately a form of patient advocacy.

“[As interpreters] we’re going to have some creative freedom as long as we don’t change the essence of what’s being communicated between the provider and the patient,” he said. “And that freedom requires being aware of many different issues, from the demographics, to cultures, to vocabulary.”

The voice of a patient

Miranda-Leon has nearly 23 years of career experience, and emphasized the role that medical interpreters play when mediating patient-provider interactions.

“When you’re an interpreter, you’re just a voice in the middle that’s going from one language to the other,” Miranda-Leon said. “You don’t add, you don’t subtract, you say exactly verbatim how everything is said. So if you feel that the patient is not understanding it is your job to let the provider know.”

A hospital setting largely influences the type of cases medical interpreters take on, said Miranda-Leon, heightening the necessity for accurate, yet sensitive responses to patient needs.

On any given workday an interpreter may need to visit different floors within the hospital, or travel to a regional clinic – hence their schedules are not always set in stone.

“Every day could be a learning experience for you,” Miranda-Leon said. “There could be something maybe when you walk into the cancer center, and there’s a new diagnosis that you have never heard of. So now your job as an interpreter…you have to ask the doctor or provider to explain it to you so that you can explain it to the patient.”

While varied interpretation mediums are essential for accessibility, the team prioritizes face-to-face care when possible.

“In-person interpretation is the best option,” Aldana said. “Because it’s more personable, that gives you that sense of trust and security…interpreters that are local, they know the area and then the interpretation process is a lot simpler.”

Liu added that when there is an existing connection with a patient, it helps an interpreter to remember their diagnosis and work with them throughout their time at the hospital.

“I will say the live interpreting is the best because you can see your patient’s face, you can see your provider, you can catch up things from their expressions,” Liu said. “[With video], you don’t know who’s in the room. You have no sense and you cannot really help the patient after the session.”

The intricacies of language in a medical setting

Live services also allow for interpreters to recognize verbal communication more, where points of clarification or further questions are best asked during a follow-up appointment.

“When you are an interpreter, you have to realize that the patient’s life is in your hands,” Miranda-Leon said. “So if you make a mistake, you can actually cost that person their life.”

Miranda-Leon is from Puerto Rico, and noted the variety of expressions, idioms and other figures of speech in Spanish—specifically, the Spanish shared between Aldana from Venezuela, and Verea from Cuba.

“On the island of Puerto Rico, a trash can [for example], we say ‘zafacón,’ where [in] Venezuela, it’s ‘papelera,’” she said, “Although we’re all in the Hispanic culture, we call it a different thing…but you also want to make sure that you’re getting your point across.”

It is common to have patients that they’ve worked with for years, said Verea. Honing in on a patient’s case is an ability that improves with time, as an interpreter has to build trust with each person they see to address medical issues with confidence and clarity.

Miranda-Leon reiterated the importance of building and maintaining a relationship with patients: “We are also their cultural broker…At least to me the model is, ‘I treat my patients the way that I want to be treated.’ And [in] the way that I would love one of my loved ones to be treated.”

Adjusting interpretation services to meet evolving needs of communities

Table B16001. “Language Spoken At Home By Ability to Speak

English For The Population Five Years And Over.” Graphic by Catharine Lee.

The evolution of Cooley Dickinson’s interpretation department mirrors the ebb and flow of populations arriving in the Pioneer Valley. After Aldana came into her role, the increase of Khmer and Chinese-speaking populations in Hampshire County prompted the search for a Chinese interpreter on staff, the position now filled by Liu.

“I think most [of the] Chinese population is in the Amherst area because of the college and their parents here,” Liu said. “[In the] Amherst area, I think I have a lot of [chances] to help people here because a lot of people work for UMass and their different departments. So some of them [are] working in the restaurant cafeteria there, [where many] don’t have enough medical terminology to go to doctors.”

The most recent population changes Aldana observed are in the Cape Verdean population, but there are no Cape Verdean or Creole interpreters in the area. Aldana fills this gap through video services, but some patients who speak Cape Verdean can understand Portuguese as well.

Aldana added that the decreasing availability of interpreters in the area is a consequence of the pandemic. While recovery has been gradual, services for the Cambodian Khmer-speaking population remain difficult to provide service for.

“[Khmer] is something that has been really impossible to get and even though we have different agencies, it has been really hard for us,” Aldana said. “Having the video alternative has been crucial for us in order to be able to help our patients that speak [Khmer].”

Ensuring that the quality of care is not compromised is particularly important amidst cultural differences. These differences are often seen in patient’s perception of healthcare from their countries of origin, as compared to the U.S.

Aldana notes how interpreters “bridge” gaps between patients and providers where a cultural nuance can hinder clinical care.

“I speak Spanish and I see [the] differences,” Aldana said. “Many Spanish-speaking countries are very paternalistic in their healthcare. They will tell the patient, ‘You need to do this.’ Here in the United States, they give you options. Patients will come and say, ‘I came to a doctor, why [is] the doctor asking me what I think about it?’… so that sort of difference we help them navigate as well.”

Looking ahead

As artificial intelligence platforms such as ChatGPT and generative video programs are cropping up, Verea understands concerns for the medical interpretation field, but recognizes that technology can’t be stopped.

“I mean, this whole thing of video and artificial intelligence and all these things are a way for institutions to save money,” he said. “When the quality of the interaction between provider and patient is going to suffer it’s going to become less personalized, and luckily at Cooley, we’re still there.”

The healthcare industry is still grappling with the impact that the pandemic left on workforce availability. From nurses to even janitorial staff in clinical settings, the effects of this shortage are hard to miss. In the department, Aldana and her team are working to ensure patients can make appointments and use their language line in a timely manner.

Ultimately, building awareness for patients about what their rights are is the first step in prioritizing better health outcomes of non-English speakers, Miranda-Leon said.

“I think sometimes people don’t realize how important language access is,” Aldana said. “And that’s something that needs to be really taken seriously.”

Catharine Li can be reached at [email protected] and followed on X at @catharinexli. Olivia Capriotti can be reached at [email protected] and followed on X @capriottiolivia.