Yes, there are monkeys at UMass

The Lacreuse Lab was small, consisting of several rooms on each side of a short, fluorescently lit hallway. The kitchen was to the left, containing an array of applesauce, fruits, mealworms and “Monkey Jumble,” a trail mix that smelled good enough for even us to eat.

That was one of the first things Dr. Agnès Lacreuse told us when we first spoke to her: “I’m sure they eat better than any of you.”

Two doors down from the kitchen were the monkeys. Before we could go inside, we donned shoe covers, lab coats, face masks and two pairs of gloves just in case the monkeys nibbled our fingers while we fed them mini marshmallows, their favorite treat.

The room was warm and humid, “to mimic the tropics where marmosets are from,” Lacreuse said. There were seven tall cages around the walls, and behind each cage were two little faces staring at us, eyes that followed us everywhere we went.

Marmosets are tiny. And extraordinarily cute.

The more courageous ones immediately jumped to the walls of the cage to investigate their guests, enthused to find that we came with snacks, which they happily took right from our fingers. The shyer ones hid in their corners and only approached a marshmallow when it came from Lacreuse’s hands.

As we looked around, the monkeys watched us curiously and chittered like birds. Eventually, some got used to our “oohs” and “aahs” and started grooming their cage partner or lounging in their hammocks, but a couple remained clung to their cages, watching. The two of us approached a pair and stared right back.

“Watch out, they might pee on you,” Lacreuse laughed as we backed away.

In May of 2021, the nonprofit animal rights organization People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) sued for the release of lab documents and launched a campaign to shut down the use of nonhuman primate research at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

The Lacreuse Lab, led by Professor of psychological and brain science Dr. Agnès Lacreuse, is the only non-human primate research laboratory on campus.

While students at UMass appear to recognize PETA’s presence on campus, many fail to understand what Lacreuse researches and why. Freshman applied plant and soil science major Lucy Stevens said that when she first saw the flyers, they challenged her impression of UMass’ practices.

“I was very confused, because I feel like UMass is progressive, so I was surprised that they were doing animal testing,” Stevens said. “But I also don’t know what they’re actually doing to the monkeys.”

Lacreuse studies cognitive decline and sex differences in aging, focusing on how they correlate to Alzheimer’s Disease and women’s health. Additionally, she studies the effects of an estrogen production inhibitor that could help treat breast cancer patients undergoing estrogen deficiency, a common side effect of chemotherapy and hormone therapy treatments.

Marmosets, a small monkey native to South and Central America, are used as a model for her research. Lacreuse said their short lifespan and neuropathology allow her and her team to examine how behavior and cognition are affected by age.

Lacreuse said she conducts her research through non-invasive testing to measure cognitive function, odor detection, fine motor mobility, sleep quality and temperature.

However, PETA aims to end the existence of the Lacreuse Lab, with an overarching institutional goal to eliminate speciesism, or a bias favoring the interests of humans over other species, and human supremacy. Their campaign, through advertisements, flyers, organized physical demonstrations, vans with screens depicting pictures of marmosets and multiple web pages, aims to shed light on the question of whether animal research is still relevant.

“We have constantly heard people saying, ‘I’ve heard a rumor that there’s this monkey lab, there’s some secretive thing,’” said Amy Meyer, PETA’s associate director for primate experimentation campaigns. “We view it as our role to show what is happening so that people understand, and then they can look into it for themselves and see if this is worth all the suffering.”

Dr. Katherine Roe, a neuroscientist and chief of the science advancement and outreach for PETA’s laboratory investigations said that in 2020, a donor to UMass brought the non-human primate testing to PETA’s attention.

After a meeting with the donor and some members of UMass administration, PETA kicked off its campaign against animal labs at UMass on May 6, 2021 by putting up a display in Amherst Center called “Without Consent.” Days later, PETA ramped up its efforts and began placing advertisements in the Boston Globe and the Daily Hampshire Gazette and drove mobile billboards around the area.

By this point, the Western Massachusetts Animal Rights Advocates (WMARA) also began participating in efforts to shut down the lab.

“PETA founded this campaign back in 2021 and they didn’t even contact us. I don’t even know if they knew about us, but we decided we’re going to join them,” said Sheryl Becker, founder and president of WMARA.

WMARA activist Steve Baer said they get their materials and information solely from PETA.

“WMARA is getting fed by PETA at this point, because someone big has to spend the money to do the research for information, pay for literature, and WMARA has tagged onto them,” Baer said. “[WMARA was] looking for a sugar daddy to help them get things done rather than reinventing the wheel. The leaflets and posters come from PETA.”

Both PETA and WMARA have gone to extensive lengths to draw public attention to this issue, including interrupting Lacreuse’s lectures at conferences.

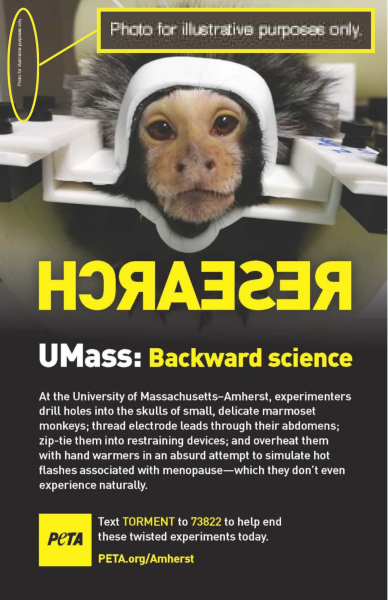

Additionally, photos of non-UMass monkeys make up a portion of PETA’s campaign literature, including the main flyers and posters that are distributed on campus. PETA obtains these photos from various other sources, including the National Institute of Health (NIH), in order to illustrate the procedures they claim Lacreuse utilizes.

Photos obtained through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) from the Lacreuse Lab are demarcated by the plexiglass “transport boxes” that the marmosets are tested in, and non-UMass photos are marked with a small disclaimer saying, “For illustrative purposes.”

“I don’t think it’s misleading, as long as what we’re depicting is related to what’s happening in the laboratory,” Roe said. “It’s misleading for Lacreuse to use an image of a marmoset not being experimented on her lab’s website or in her publications or in any of the PR material that they put forth.”

Any campaign materials featuring a photo of a non-marmoset monkey, such as a rhesus macaque, do not originate from the Lacreuse Lab.

In general, the UMass community’s reactions to campus protests vary. 2023 UMass alumni Adam Jones said that he wasn’t bothered by PETA’s presence, but some students were agitated.

“I thought it was funny because they had a gigantic sign of a monkey,” Jones said. “But they were very aggressive outside that area, and for many people heading to their classes, it became very annoying because they kind of got [in] their way. People definitely had issues with it, especially those who were kind of science focused and were actually doing some [animal] experiments and working with the professors doing them.”

PETA’s online campaigns have directed extreme animal rights activists to Lacreuse, who said that she gets threatening emails from unidentifiable individuals that resonate with PETA’s messaging.

“I receive hateful messages saying, ‘you should be shot,’ and stuff like that, but it’s never signed,” Lacreuse said. “I receive that regularly. This is how I know that PETA must have put something else out there, because all of a sudden, I receive hateful messages, and I’m like, ‘oh, there must be another statement from PETA.’”

“Agnes’ family feels threatened, her kid, her students,” Dr. Heather Richardson, graduate program director in the neuroscience and behavior interdisciplinary graduate program, said. “It’s just taken a toll on her, and as a friend and a colleague, it’s hard to watch.”

Lacreuse is not the only UMass faculty that has been targeted by PETA nor the only animal researcher at UMass.

Paul Katz, professor and director of the Initiative on Neurosciences, studies the neural circuits of sea slugs and how and where in the brain they correlate to behaviors like swimming. He said sea slugs are not even advanced enough to be categorized as animals under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee standards.

“I, of all people working on animals, have the least to worry about,” Katz said. “That’s why I feel like I need to put myself out there as much as I can. But there is fear, there’s real intimidation that has gone on.”

Katz made a statement to news cameras at one of their protests, where he said biologists love animals and want to understand them without the intent to harm them. He said he was then targeted on Oct. 4, 2021.

“You know what PETA did? They took out a full-page ad [in the Boston Globe] with my quote and said, ‘Oh, you don’t like animals? Paul Katz in the biology department thinks that animals don’t suffer. Well, what about this?’ And then they show horrific-looking pictures,” he said.

Dr. Luke Remage-Healey, professor and researcher within the department of psychological and brain sciences, uses songbirds to study vocal learning and brain plasticity. While he has received some attention from PETA for his practices, he said that they have not nearly been to the scale of Lacreuse’s, which he thinks is because he is male.

“If you look around the country, PETA is targeting women,” Remage-Healey said. “They are targeting women who work with nonhuman primates. That’s one of their goals, is to push on people they feel are vulnerable in a bothersome way to interfere with research.”

However, PETA denies those claims. Dr. Alka Chandna, vice president of laboratory investigations cases at PETA said, “PETA’s founder and president for the past forty-four years is female, all of our senior staff is female, the senior vice presidents, the vice presidents. It’s a ninety-five percent female organization. We have a long track history of going after a whole bunch of white men.”

Yet, among the six UMass faculty members the Massachusetts Daily Collegian spoke with, there was a unanimous opinion that PETA consistently targets female researchers.

“You look at the pattern over the years, it’s very clear. It’s part of a coordinated approach to target individuals who potentially they see as most vulnerable. [Lacreuse] is a woman scientist [studying] women’s health issues,” Dr. Ilia Karatsoreos, professor and chair of the department of psychological and brain sciences, said.

Public universities like UMass are subject to the FOIA because they receive federal funding. Karatsoreos said the University could more efficiently support researchers who receive requests for public records.

“When you get a request for documents, it takes a lot of time to sit there and go through all these different kinds of things, and we’re not lawyers,” Karatsoreos said. “It puts a faculty member in a very difficult situation because it eats up a lot of time.”

Remage-Healey said that one of the women PETA has attacked is Associate Professor Christine Lattin at Louisiana State University (LSU). PETA began campaigning against her during her postdoctoral research at Yale University and sued LSU in 2020 and 2023 for failing to provide records requested by PETA for her work on sparrows – a suit LSU lost.

“If you want to see the conditions of the sparrows in captivity, you can watch some of the videos on my website, because we don’t have anything to hide,” Lattin said. “At the same time, I haven’t finished analyzing those videos, and it’s possible now that somebody could use [my] data, and they could publish it before we get a chance to do that.”

Lacreuse said that, while occasionally bothersome, making animal research more accessible to the public is ultimately a good thing. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) posts all cited animal research incidents on their website, which she said is “one way that animal research can be more transparent.”

Regarding transparency, however, Roe said that in 2020 PETA offered to the UMass administration to give non-animal alternatives that would be “much better science, and certainly much less ethically concerning as what’s going on now, but those requests were declined,” Roe explained. “We offered to have a lively but good-natured debate about the utility of these experiments, but that was also declined.”

Additionally, Chandna said no representatives or members of PETA have physically entered the lab or requested to do so because she said it could cause psychological distress to their animal rights activists. She did not comment further on potential undercover operations to enter the lab.

Lacreuse said that she would welcome PETA representatives to see the lab, but doubts PETA’s interest in genuinely promoting animal welfare due to what she sees as disinterest in a thorough search.

“It has nothing to do with animal welfare. I’ve been harassed by these people for three and a half years now, and not once have they asked to visit my lab,” she said. “This is such a scam, because you would think that the first thing they would ask for is to see the animals, [to] verify that they’re in good health. No, they have no interest. It’s about claiming that, ‘we ended primate research at UMass, give us more money.’ It’s a fundraising machine.”

“At the University of Massachusetts–Amherst (UMass), experimenter Agnès Lacreuse drills holes into the skulls of small marmosets, threads electrode leads through their abdomens, zip-ties them into restraining devices, and overheats them with hand warmers to simulate hot flashes associated with menopause—which they don’t even experience naturally,” PETA states on their website, drawing from information found in Lacreuse’s published research papers and through materials acquired through open records requests.

According to Lacreuse, the first two claims are based on a procedure done multiple years ago on approximately nine marmosets, which has since been replaced with a Fitbit-like device attached to a collar so it would be non-invasive.

The procedure was used to track brain waves as the monkeys slept and was performed through anesthetized surgery by veterinarians who planted a device on the scalps of the marmosets and threaded electrodes through their abdomens.

“To place the electrode on the scalp, you have to drill to put the electrodes in,” Lacreuse said regarding the former procedure. “It doesn’t affect the brain, it’s all around the brain. The monkeys [did] not have something on their head. The system [was] completely enclosed.”

Lacreuse said that PETA’s third claim, zip-tying the marmosets into restraining devices, is entirely false. Any test that may require the marmosets to sit still is done without restraints, and the marmosets are trained for a minimum of five weeks for the activity, according to Lacreuse. She said for necessary neuroimaging, the lab has helmets made specifically for each monkey.

However, Roe said that Lacreuse’s published paper in 2019 cited using “a state of the art technique developed by Dr. Afonso Silva (Silva et al., 2011), to image awake marmosets without the use of anesthetic.”

The paper said, “Each animal wore a sleeveless jacket (Lomir Biomedical, Inc), which attached to a semi-cylindrical plastic cover made of Lexan, restricting anterior or posterior movement but allowing the animal to move its arms, legs, and tail freely. The plastic was attached to the back of the marmoset’s jacket using plastic cable ties.”

“I think we did that in 2017, perhaps 2018, not after,” Lacreuse said. “And it’s only for this particular experiment that the monkeys had to be restrained for this imaging session. To get there, we train them for a minimum of five weeks. They’re restrained first for 15 minutes, and then for 30 minutes, in different sessions, until they tolerate it.”

Lacreuse said in the event that imaging is too stressful for some of the marmosets, “we don’t force them.” Marmosets are rewarded with marshmallows after each session.

PETA’s fourth claim, overheating the marmosets with hand warmers to simulate hot flashes, involves two circumstances.

The first was an incident that occurred in the lab on Oct. 2, 2015, where UMass veterinarians reported a marmoset death after not receiving a proper heating blanket after surgery. Lacreuse said that neither she nor her lab members were involved in that “horrific accident that traumatized everybody.”

The second involves lab simulations of hot flashes in its research. The test involves researchers holding the monkeys in their laps and wrapping “a single water pump controlled heating pad” around the marmoset to measure the temperatures of the marmoset’s faces through thermal imaging, according to Lacreuse. This is done to understand how thermoregulation occurs during hot flashes, a common menopause symptom.

“The monkey is sitting on our laps, and they’re surrounded by heating pads that we are holding with our hands so we have the heat on us too,” Lacreuse said. “It is temperature-controlled and only for 20 minutes at a time. There is no way to burn them.”

A letter to USDA and an animated video by PETA detailed the account of a marmoset named Chewie. PETA said “the laboratory’s daily record showed that his tail had been accidentally torn off after it became caught in an air duct,” and that, “his tail was so badly injured during recapture that it required amputation.”

Chewie’s vet record on Apr. 25, 2017 said about one cm from the distal tip of his tail was amputated, and was recorded as a “clean amputation… no suture or bandage required.” Lacreuse, taking full responsibility for the incident, said that Chewie was immediately cared for by veterinarians.

“He completely recovered from that. Chewie lived for a very long time after that; he was obviously taken care of and was receiving pain medication,” Lacreuse said. “But the system worked. You must self-report it to the Office of Animal Welfare when you have an accident. They forward that to USDA, which gives a citation. With a citation, you have to correct what happens so that it never happens again.”

PETA also questions Lacreuse’s choice of the marmoset as a research specimen as marmosets do not naturally experience menopause or exhibit menopausal symptoms.

Roe said inducing menopause symptoms in marmosets is scientifically invalid and that removing their ovaries is not the same as spaying and neutering because it is not done in the interest of population control and is “in [Lacreuse’s] best interest.”

“A female marmoset is reproductively active basically until the day she dies. They also don’t respond to exogenous hormones the same way women do,” Roe said. “This is possibly the worst species of animal that could have been chosen to try to study human menopause because they just don’t get it.”

However, Lacreuse said that although only a few mammalian species (humans, chimpanzees, and whales) undergo menopause, the marmoset becomes an optimal model after the ovaries are removed. This removal, Lacreuse says, is the same as when pet owners spay and neuter their dogs and cats.

“Women can expect to live 1/3 of their lifetime in a menopausal state, so it’s a huge time without estrogen. We model that by suppressing estrogen by removal of the ovaries,” she said. “This is surgical menopause, and that models it perfectly. So, yes, it is not the same as natural menopause, but we model the hormonal milieu and then can assess different things.”

UMass Director of Animal Care Services Dr. Michael Esmail said that removing reproductive organs is also done to animals to prevent cancer and infections or induce a behavioral change. However, Esmail recognized how the circumstances here are different.

“We don’t want the marmosets to be giving birth to a lot of other marmosets, that’s not part of their purpose here,” he said. “There’s not been a situation where I’ve felt dogs and cats are suffering because they’re not intact, and I would say that to be true of all animals. Having gonads is not going to be a critical component of their overall happiness in the world.”

Dr. Lisa Jones-Engel, PETA’s senior science advisor for primate experimentation, was a primatologist for three decades before she switched to animal rights activism. A former Fulbright Scholar, senior scientist and professor within the Department of Anthropology at the University of Washington, Jones-Engel said that she had a moment of clarity after studying primates, specifically the Rhesus Macaque, for many years.

“Anyone who sees what it really is and really knows what it is for the monkey, you don’t come out of that experience the same person,” Jones-Engel said. “You simply can’t, because you look into the eyes of a monkey in a cage, you have a reflection of self. You also have, if you were looking, the understanding that a person is a prisoner in there.”

Upon finding out that UMass takes part in animal research practices, freshman environmental science major Bridget Williams said that regardless of the research that’s being done, it’s unacceptable to be doing research on animals.

“I don’t think the way to go about finding those solutions is to be testing and doing these procedures on the monkeys,” she said. “They’re living things too, and they shouldn’t be harmed like that, especially if they were just born and raised to have procedures done on them.”

However, alum Jones agrees that testing within research is necessary and said that if the choice were to test on animals or humans, he believes that humans should be prioritized.

“Testing has to be done regardless, and I don’t think it matters what creature is used, whether that’s a human or any other type of animal,” he said. “It should just be about whatever is safe for everyone.”

The solution PETA proposes is for Lacreuse to stop her research and rehabilitate the marmosets so “they can live out the remainder of their lives in peace” according to a PETA article written by Keith Brown. Chandna said Lacreuse could continue her research using alternative non-animal methods, such as humans who experience menopause or organ-on-a-chip, which are systems containing engineered or natural miniature tissues grown inside microfluidic chips.

Becker also said that technology should be more advanced to run clinical trials without using animals and that some breast cancer patients might be interested in testing Lacreuse’s estrogen compound.

“There is a serious gap in our health system in this country, but I don’t think that using humans is an issue at all,” Becker said. “Our government needs to revamp the whole system, of course, but people who are suffering financially and health-wise would be glad [and] open to trying it … and honestly, these people who choose to do the research are not being forced. They’re not being pressured, and many of them are desperate.”

However, researchers at UMass said it’s not that simple.

“Right now, people can take human embryonic stem cells and grow little brain organites from those pseudo-cells that have some features that look a little bit like a brain, and these are the size of the tip of your finger,” Remage-Healey said. “It’s not the same thing as how the human brain develops, or even how a nonhuman primate brain develops.”

On the other hand, Lacreuse said that practically, there are too many uncontrollable elements in human testing and it would not be humane to test the compound on women before she knows how it affects the brain.

At the end of Lacreuse’s studies, and as the marmosets reach the end of their lifespan, they are euthanized at UMass by veterinarians and Lacreuse continues analyzing their brain tissue.

“We’re really attached to these animals,” Lacreuse said. “But my duty as a researcher is to be able to provide all the information we can from these animals, and that includes analysis of brain tissue and some of this information we cannot get any other way.”

To ensure that any procedures conducted at UMass are ethical, valid and humane, the International Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) oversees all animal research labs as an external body.

However, to WMARA and PETA, the ethical checks in place are not enough, even if the science conducted is deemed relevant by national bodies like IACUC, USDA and NIH and follows the Principles for the Ethical Treatment of Nonhuman Primates from the American Society of Primatologists.

Dr Mélise Edwards, a former graduate student researcher in the Lacreuse Lab, said that she encourages the questioning of scientific methods and animal research practices. At the same time, she is disappointed with the way that PETA conducts its advocacy.

“A willingness to engage in deeper conversation could have been an approach that established a connection between researchers who care about animals and people in the community who care about animals,” Edwards said. “Instead, PETA seems to resort to clickbait articles to instill rage in the public — a great model for generating donations by feeding off of the reactivity of a largely ignorant base that isn’t aware of what animal research is.”

As we spoke with the monkeys’ caretaker, we could hear Lacreuse in the back speaking softly to the monkeys in French. They almost responded immediately back to her — even the most timid ones noticeably relaxed when she approached them.

Lacreuse brought out the transport box that the marmosets’ testing is conducted in to attach to one of the cages. As soon as she fastened it on and slid the door open, both marmosets quickly jumped in to get a closer look at us.

One stayed in the box for a while and his long, fluffy tail half hung out. Lacreuse stuck her finger in the cage to beckon him closer, to which he nuzzled his furry white cheek against her hand.

“If I didn’t treat them well,” Lacreuse said, “they wouldn’t act this way around me.”

Bella Ishanyan can be reached at [email protected]. Kavya Sarathy can be reached at [email protected].

Correction: The article has been edited to reflect that Dr. Paul Katz made a statement to 22 News at a protest on 9/13/2021, not to cameras operated by PETA.