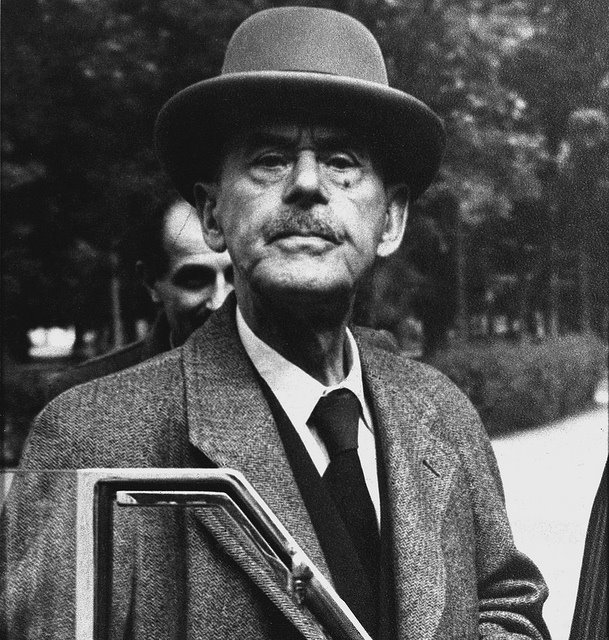

George Saunders, author of “In Persuasion Nation,” spoke on Feb. 23 at the University of Massachusetts in the Student Union Ballroom. After a Commonwealth Honors College faculty representative’s warm yet lengthy introduction, which described the writer with an exhaustive series of figurative flourishes from “comedic chameleon” to “a one night stand between Kurt Vonnegut and Flannery O’Connor,” Saunders took the stage.

Over the next hour and a half, the thin, bearded Chicagoan told the standing-room audience something like his life story. In his words, he set out to describe “the way art actually works.” As a writer, he did this by telling stories. As a funny writer, those stories tended to put him as the butt of the jokes.

The stories moved from one past misconception about the nature of writing to the next, sometimes punctuated with a moment of literary discovery. The first of these discoveries was a single sentence by Esther Forbes in the children’s classic, “Johnny Tremain.” She wrote:

“On rocky islands gulls woke.”

Saunders explained that the feeling he got from that sentence, his sheer delight in its words and syntax, is what initially drove him toward writing. That feeling is felt in his current methodology, to “put one sentence after the next. And try to make it compelling.”

“Like a dumbass, I forgot all about it,” Saunders continued. The remainders of his formative years were dominated by various pretensions.

He was crippled for some time by a condition he calls “Hemingway boner.” Its symptoms were sentences like, “Nick went into the Wal-Mart. It was pleasant.” Hand-in-hand with this affliction was his refusal to read any literature published past approximately his year of birth.

As a young man, he read Ayn Rand’s “Atlas Shrugged.” The connection he made with the book as a literary experience triggered his ensuing objectivist alignment. He went through college with that mindset, as well as being under the continuing influence of the “Hemingway boner.”

“At one point I read Kerouac, and I realized I was a corporate shill,” he quipped.

Saunders graduated from the Colorado School of Mines with a B.S. in geophysical engineering in 1981, and thereupon shipped straight off to Sumatra. He was officially there to put his engineering skills to work on an oil exploration crew, but he was really there to find what he described as his “exotic experience.” Hemingway had one, so the presumption was that all great writers must have one.

In fact, his plan was to shortcut the conception of his first real story by drawing on the Sumatran expedition for inspiration. He traveled, gained his exotic experience and moved on.

Several years later he was married, and was “kinda the photocopy guy” at the environmental engineering lab where he worked. He had a ponytail, and still hadn’t written anything he considered to be good. At this point, he was under the poisonous impression that in writing, “the reader should feel what I feel.”

He spent months of sleepless nights working on his first novel during this time. The novel’s title, which Saunders felt was the sole piece of evidence necessary to prove to us its hideous stupidity, translates to “The Wedding of Ed” (The title was originally in Spanish). When the manuscript was complete, his wife read only the first few pages before informing him that he needed to start over. She also pointed out a genuine humor in his writing, which was the part of his voice – his “most urgent self,” as he explained it – that he had been holding back in all of his pieces.

“I would always be funny,” he said. It was this monumental realization that eventually pushed his writing into maturity. He stopped worrying about making the reader feel, and allowed himself to feel the writing himself.

He once asked his editor at the New Yorker, admittedly fishing for a compliment, what he liked about his stories.

The editor, Bill Buford, said, “I read one line. And I like it. So I read the next one.”

This, for Saunders, is success. He explained that all he is really trying to do in his writing is “keep your attention away from the Nintendo for a few minutes.”

Writing now with more spontaneity, he finds that conceptual elements – such as character development, plot and theme – no longer require much thought.

“It all sort of magically appeared,” he explained.

Having at this point in his talk (and career) finally reached a moment of lucidity, Saunders turned over the floor to the audience.

One question concerned the role of consumerism in his stories.

“I kinda like it,” Saunders said. He qualified this by admitting that, partially due to commercial media saturation, “our country has gone from a spiritual culture to a material culture.” He explained that a bit of cognitive dissonance is healthy, at least for a writer.

“Take this argument and this argument, sit them down, and let them resonate,” said Saunders.

Several of the questions that followed centered on the same theme. The subject matter in Saunders’ stories generally includes some form or derivation of consumer culture, so this trend came as no surprise.

One audience member asked if Saunders sees himself in any of his works. Seemingly caught a bit off guard, he confessed that “Jon,” one of the stories from “In Persuasion Nation,” was in part about the relationship between him and his wife.

“She has taught me so much about how to grow up,” he said.

The growth Saunders has experienced as a person, but more saliently as a writer, guided the course of the speech last Tuesday night. Carefully communicating the process of self-education through repeated failure, he gave the audience a richly entertaining and insightful rendition of a time-honored lesson: Learn from your mistakes.

Garth Brody can be reached at [email protected].

Floyd Flanagan • Dec 12, 2010 at 4:09 pm

Please listen to the first sentence of the video novel, and if inclined continue. It goes on for quite some time.

–Floyd