Junior Adrianne Smith had desperately wanted to be a vet since she was five years old. She came to UMass her freshman year on the pre-veterinary track. Then, the fall semester of her sophomore year, in the wake of the Michael Brown shooting, she took a weekend-long seminar on racism.

Being a person of color in the midst of the reemerging anti-racism movement, she said, was emotionally draining.

“I’d hear things of killings and stuff prior on the TV all the time and it never made a connection to me, but this case … I think it’s the blowup of it that really affected me. I remember hearing the verdict, being in my dorm room, and just crying about the Michael Brown case – for hours, just on and off. I felt so hurt,” she said. “I think that’s when it hit me that I am a person of color and that is how I’m viewed in this world and how, because of the color of my skin, I’m not guaranteed justice.”

The “weight of it all,” she said, became real after that, and she decided to take more classes. From there, she was engulfed in the topic.

Racism, the color of her skin, white privilege, being mixed race – these things were all she could think and talk about. She began asking questions she had never asked herself before: What are white people thinking about these things? What are black people thinking? What do her parents think? What does it mean to be a black man in America? A black woman?

Her local non-denominational church, the Chicopee Church of Christ, held a few forums last year to help people talk about the issues in the shadow of the brutality. Smith attended one and said it was a good conversation, but she was the only college student there and left wanting more.

“I just remember being very angry,” she said. She had to remind herself that it was not that the church did not want to help in some way, but their education and knowledge on the subject was wanting. “Like, how do you facilitate something like this?”

She also felt, after taking these classes surrounding social and racial issues, that the Christian part of her identity was not welcome in the social justice world she became engulfed in, and vice versa. The Christian in her wanted peace, but the girl in the classroom wanted change. At the time, there did not seem to be a bridge between that gap.

Then she realized that she needed to become that bridge – through her career. Being a vet, she decided, was not an option anymore. While passionate about animals, she decided she wanted to work with people instead, particularly regarding racial issues.

After some “major shopping,” Smith found the sociology major to be a perfect fit. Her future career, however, is still unclear. She is currently thinking about social work with children regarding identity and race.

“I will never be able to fully imagine what I’ll be getting in store for,” she said about social work. “I’m excited to be there for these kids, but I’m just also scared of the legal aspects of what my job will require me to do versus what I actually think is right.”

This is very different than the original, vet-set path she was on: Smith was a vegetarian for a long time and worked at Boston’s Franklin Park Zoo from eighth to eleventh grade. Her favorite animals to work with were the primates.

Her favorite one, by far, was a mandrill, similar to Rafiki from “The Lion King,” that would put its hand against hers through the glass barrier and mimic her every move.

But there is no protective glass barrier for Smith’s new future – in fact, the now-ubiquitous documentation of brutality against black people has exposed her and every other person of color in America to one of the most uncivilized, nefarious faces of their country, putting her in a cage of her own.

Like all American college students of color in 2015, Smith has been forced at the forefront of the social issue that the United States has dealt with since its inception: blatant and, so far, unstoppable discrimination.

Foresight

Smith is ambitious and hopeful for her career, but scared nonetheless for herself and her future family. In the wake of all of these murders, Smith said, she has realized that, not only is she a person of color, but her children will be as well.

“I have nightmares of my unborn, nonexistent son getting shot and getting murdered and killed,” she said. The pain in these nightmares is very real for her – so real, in fact, that she often wakes up crying “as if it’s happening in the moment.”

As someone who believes in the teachings of the Bible, she is conflicted with adhering to the Christian teaching of forgiveness when it comes to forgiving the murderer of her own child and trying to find peace.

“But where do you find peace in something that is not peaceful at all?” she said.

Just keeping up with news or going outside, the world can already be scary for black people in America. The future, for Smith, is just another layer of fear.

“Things like that are just terrifying. The idea that, when I raise my son, there will be people who will just think he’s good for nothing other than entertainment or sports, and that’s what he’s useful for. My son has less of a chance to be a doctor – anything that he might want to aspire to be,” she said. “Or all these thoughts like, ‘Wow. He has to fight.’”

She thinks about these things even when she sees children today.

“It’s so scary seeing little people of color running around and it’s like, ‘Dang. People look at you now and think you’re an enemy. They think you’re evil.’ Someone’s going to look at my child one day and, just based off the color of his skin, because of the genes he inherited from his parents, he’s evil because of that. Like, his heart, his intention, his education – none of those things will matter. He is an evil being just because of the pigment in his skin.”

She added, “It’s scary that that has been existing for so long.”

Smith notices she connects more thinking about the struggles of this future child than those same struggles she has had to face herself in reality.

But that does not mean she forgets.

“It’s scary that there’s people that think of me like that,” she said. “I think of jokes people would tell me in high school of when they met me, like ‘Ha, when I first met you, I thought you were a bully and mean’ and I’m like, ‘What on earth? I graduated high school winning Best Personality, and at one point someone thought I was a bully?’ Like, what made them think that? How can this person who I’ve never talked to before think I’m a bully?”

Smith, who has an immediately warm and non-intimidating presence, believes these biases may be a result of racial profiling.

Black on a white campus

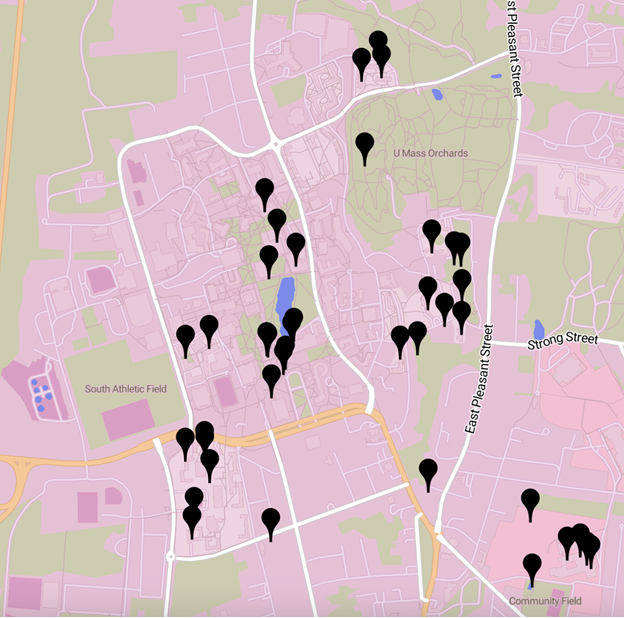

Though she now lives in Taunton on the south shore of Boston, Smith lived most of her life in Dorchester. She came from what she considers to be a very diverse neighborhood: many of her neighbors were people of color. Coming to UMass, she said, was a different experience. She lived in the Central Residential Area her first two years, where there are not a lot of people of color.

“You feel the difference,” she said. The first time she went to the Southwest Residential Area, she said, she could not immediately place why things felt different from Central, or the rest of campus. She said she realized, “Oh wow. I can count five black people in a matter of 10 seconds.”

That disturbed her.

“I remember I hadn’t seen a black person on campus in a really long time before that. I remember sitting in Frank with the open windows: you can just see different parts of campus. And, just looking out, I could see a black person and just be amazed.”

She remembers once seeing a group of 15 or 20 black people walking together. “And I was like, ‘This shouldn’t look so weird to me!’”

Now that she has more friends of color, she notices it less. She said she now feels she has a mixed group of friends, white and non-white, and her “little UMass” that she has created is more diverse than the one she began with as a freshman.

In reality, she said, UMass’ campus is not diverse. However, she said, many people believe it to be.

But diversity is subjective. “Everyone has their own definition of what diverse means. Like, you have a white student that grew up in a predominantly white institution, (with) maybe one or two black kids or people of color, and then they come here and they see more black people than that, so they think, ‘Wow, UMass is diverse!’”

Conversations arise often, she said, where people are upset and confused at the idea that UMass is not as diverse. She said they argue, “This is diverse! How are you saying this is not diverse?

“And it’s sad because … you can’t call them wrong,” she said. “For them, and their life experience, this place is so diverse. We’ve made diversity a relative thing. It’s hard to put a number on it.”

She said since UMass publicizes the statistics of the racial makeup of campus, those people would reconsider their own definition of diversity if they took time to look at it.

“And it’d be hard because you’re literally fighting what you’ve learned your whole life. Which is why racism and all these topics are so difficult – because it requires fighting everything. Like, everything you’ve learned: institutionally, socially. Everything you’ve learned has been geared toward keeping this structure in place,” she said.

“I’ve learned that people gravitate towards what they feel comfortable with. A lot of people of color gravitate toward Southwest because that’s where most of the people of color on this campus are.”

The two main things you hear about Southwest, she said, are “party” and “diverse.” She said that fact alone is frustrating because Southwest, which carries UMass’ notorious “party scene” culture, is also predominantly where people of color congregate.

“And they are connected. I can’t pretend they’re not.”

Smith recalled a disturbing – but not uncommon – instance this year: she came into class the first day and scanned the room, looking for a place to sit. She saw one other person of color beside herself in the lecture, a girl, near the front corner.

“And I’m just like, ‘I’m going to sit there. Maybe we’ll meet and talk,’” said Smith. “‘Like, she’s someone I think I’ll be comfortable with.’ I don’t know.” Smith recognizes that, while certainly prevalent, the human instinct to gravitate toward the familiar is not necessarily logical.

So Smith sat down with her. After that, another black girl walked in and did the exact same thing: she gravitated toward the same corner. This happened another time, totaling four black girls in a corner next to each other in a room full of white people.

While Smith was conscious of her decision to sit next to another person of color, she wondered whether the other girls subconsciously gravitated toward each other.

Despite how weird the situation struck her, Smith said she actually made friends within that group of girls from the lecture hall.

She also made friends with people of color at her church. It was the black girls, she said, that she became friends with first in her church. They are now the girls that she lives with. While she said she could live with anyone in her church, which is by no means segregated, the likeness of culture (food, cleanliness, et cetera) made it easy for Smith and her apartment-mates to adapt to living together.

And as a black person at UMass, she said, she does feel comfortable.

“I just don’t feel like I’m black and alone,” she said. “I feel that I have other people that I can share my blackness with and talk about things. I have people around me.”

The Black Student Union and why anger is necessary

There is in fact community on campus, for Smith and other students. And the social justice movement in the United States sometimes seems to be working at the speed and sound of a bullet train. But there is still a very long way to go.

“I think black rage is totally necessary,” said Smith.

But sometimes, she said, that rage can be misinterpreted as ignorance.

“But it’s what it is – it’s rage. And there’s a reason for that rage. We’re not just angry because we’re angry. Like, we’re angry because of the situations we’re living in.”

Smith is not a part of the Black Student Union (BSU), though she has friends in it.

“I appreciate everything they do and I appreciate their sentiment in this movement,” she said.

The Black Student Union is an activist group, and Smith said she could not fully judge them as an outsider because she does not see everything they do. There very well may be a place for her, she said, but it is still not the be-all end-all for justice: the movement needs more than just activists and protesters.

“We need so many different types of people. We need people that show their rage in many different ways. We need writers, we need reporters, people that can tell our story accurately,” she said, along with the need for black people in education, social work, and government.

“We need black people managing things so people can see, ‘Oh, I can be a person of color and not be low. … I can be something.’”

Not that Smith has never been pressured to join BSU.

Once, Smith was near the library, inviting people to attend her church, when one invitee, a black woman, asked, “How have I never met you before?”

Indeed, on a campus of around 30,000 students, there are lots of people that never meet. But Smith speculated it was because they were both of color, further showing how small the black community at UMass is.

To further perpetuate stereotypes, the woman falsely assumed she lived in Southwest. Smith corrected her. “And she was like, ‘Hm. You need to join BSU.’”

They exchanged information and texted a couple of times, but Smith never attended a meeting.

What struck Smith about the situation was the woman’s attitude: just because Smith was a person of color, she was expected to join.

She has nothing against the organization.

“It’s just not the place for me,” she said. “I feel like there’s a lot that I can do to help with this movement that doesn’t mean I have to be a part of BSU.”

Smith added, “They need the support from the black community overall to really be able to work. I want to be that support for them.”

Smith has a lot of friends of color both in and out of BSU. One of her friends from high school is on the executive board. On the other side of the spectrum, she said, she has friends of color that do not care about these topics at all.

But most people do care. And with booming protests like the recent ones on UMass’ own campus, it is arguably hard not to.

No justice, no peace of mind: #StudentBlackOut

The Student BlackOut, was one such protest, a class walkout that began at Roots Café in solidarity with the students at the University of Missouri and other college campuses across the country that, according to the Black Student Union’s official Facebook page, are “uncommitted to the recruitment, retention and safety of Black Students.”

The protest was a success: a mass of students charged through campus with megaphones and chanted like thunder. But what affected Smith most was a chant: “If we don’t get no justice, we don’t get no peace.”

The original chant is “No justice, no peace,” which Smith interprets as justice and peace being directly correlated. But the slight change in the wording concerned her because it implied a threat.

“I remember being like, ‘What does that mean? I’m not going to do anything to destruct the peace of others. I just want peace for myself.’”

It made her feel very misrepresented as a person of color.

Smith actually was caught up in the march by accident, but she was not completely caught off guard when she was buying a meal in the Student Union and the march came through.

“Some days before, some friends in a class were just kind of like, ‘Look out for Wednesday. Like, that’s all I’m going to say. Just look out for Wednesday.’”

She could not initially make out what the crowd was chanting. The march stopped, formed a circle and people took turns shouting into a microphone. Smith watched and listened, agreeing with many of the things being said.

Then the march continued from where she was standing, putting her inadvertently at its front.

So began an internal battle for Smith.

“It was just weird,” she said. “I was like, ‘Alright, I was fine just listening but I don’t know if I want to march.’ I remember feeling conflicted,” she said. “Like, if I just stay still and let them pass me, will they judge me? Like, ‘Why isn’t she walking, too?’”

So she chose to walk with them.

“I was like, I’ll just walk with them until we get to the exit and I’ll leave.”

As she walked, she felt conflicted again, this time on whether or not to chant. The protesters began chanting, “If we don’t get no justice, we don’t get no peace.”

So, at first, Smith joined in.

“And I’m like, ‘I don’t believe this. I don’t agree with this.’ And I stopped.”

She repeatedly started and stopped chanting, deciding finally to only chant the phrase “If we don’t get no justice,” leaving out the “no peace” part. She pointed out that even the first half of the chant still contains the slightly threatening “if.”

When the march left after continuing through Blue Wall, Smith said she sat down. She thought to herself, “What just happened?” and ran the chant over again in her head.

She speculated that it might have merely meant that, if black people did not get justice, people could not peacefully eat in Blue Wall. But maybe it was more than that.

“It’s a violent phrase. It’s angry. The tone was angry. Everything about it just felt very violent to me. And it’s not my nature.”

But she still empathized with those who were chanting without holding back. “It’s so complicated. I understand that, to a degree, that work is necessary.”

Again, the anger is warranted. Racism is more violent than people may see on the surface, and it affects people beyond just physically, such as with the brutality seen on the media: it is also mental and emotional.

But should violence be met with violence?

“It was a two-minute walk that just messed with me so much,” she said.

Smith said there is a common mindset that, if one is not actively fighting against racism, they are passively going along with it.

“I feel like that idea is being thrown at people in so many different ways,” she said. Protests and “big action things” like the BSU Student BlackOut are the most obvious cases of anti-discrimination movements, even in the media. Therefore, people could falsely believe protesting is the only way they can participate in the movement and thus will feel pressure to join.

The protests are important – “Presence is such an important thing,” Smith said. But sometimes they can be misdirected. While being unified and having bodies to protest is amazing, education is lacking. Rallies and protests, she said, need to come after education.

“There’s people that literally go to these protests and don’t educate themselves on the matter. And that’s scary that they’re just there. And they’re feeling enraged and they don’t know what they’re enraged about,” Smith said.

She remembers watching a “random protest” on the Internet within the last year, in light of the Michael Brown shooting, where interviewees were “saying the most ignorant things.” Smith said many people, despite their intense anger, do not understand where their oppression comes from. She compared the whole instance to a herd of “black sheep” blindly following the movement, which disturbs her.

“If they don’t really know what’s going on, they can’t really deconstruct anything,” she said. “They’re just a body.”

Mixed family, mixed identity

Smith is straddling multiple worlds: a Bostonian in western Massachusetts, a Christian passionate about social justice, a racial minority on a white campus, a black person not in the Black Student Union, a protestor only chanting the first half of the chant.

Being caught between two worlds is nothing new to her. Smith is also biracial.

“I had my white mom, and I had my black dad. So a bunch of things clashed,” she said.

For one, she does not look like either of them.

“I’m significantly lighter than my father and significantly darker than my mother. And just everything about me was just a spectacle growing up.”

For example, her mother’s side of her family would compliment her on her dark skin and thick hair. With her father’s family, it would be the same compliments, except switched: now, it was how fair her skin and not kinky her hair was.

Smith remembers being in grocery stores with her mother as a child: “I’m at her side, like, little, young, light-skinned, curly-haired girl. And people would come up to me and talk to me and be like, ‘Why are you by yourself? Where’s your mother?’ and my mom, usually standing right next to me, would get very defensive and be like, ‘I’m her mother,’ and be upset that what to her is very overt discrimination, like ‘How can you not tell this is my child? Why are you bothering her?’ She would get angry. I remember seeing her angry.”

Smith believes her mother’s anger was warranted because she dealt with her own adversity. “Even just choosing to be with my father meant getting kicked out of her house because her parents were racist and didn’t approve,” she said. She has never met her maternal grandfather. “He never held me or my sister, ever.”

Smith said her mother, however, sees her children differently than other people of color. “It’s like I’m not ‘one of them.’ Whoever ‘one of them’ is. She treats me a certain way and then goes out into the world and sees other people of color, and it’s like she hadn’t gone through all those things. It’s just she just forgets what she went through to have this colored family.”

She added, “It’s just sad because racism is such a tricky thing in that it changes and evolves in so many different ways in that, if you don’t actively keep up with it, it can really get ingrained into you.”

That is the original image Smith has had of her mother. But, as she has grown up, that image has changed.

“Now, learning more about our colorblind society, myself and seeing how that affects me, now almost seeing her in a new light of, ‘Wow, she doesn’t get it anymore.’ Or she just doesn’t go after it anymore. She’s learned all she has to learn about racism. She’s already married to this black man, her kids are already adults … it’s not her problem anymore.”

Smith said her mother has a “very interesting mind” because, while she recognizes and is against blatant racism, she does not see the full picture.

Smith remembers an instance of this ingrained racism in her mother this past summer, when a maintenance worker came to fix the rug of their apartment.

“He was Hispanic or Latino, I don’t really know,” she said about the worker. “His English wasn’t amazing, but it was understandable if you took a second to really listen.”

Despite that, Smith said, her mother was unnecessarily short with him. “Watching it was just disgusting. Like, I’ve never seen my mother be rude to anyone, really. Unless someone seriously provoked her – but even then, not really.”

When he would leave, Smith said, her mother would make racist comments, such as, “I know he’s just trying to rip me off.” Smith, confused, argued that he was just trying to fix their carpet and there was no reason to get upset.

“She would just get upset at me, like, ‘Stop it. Stop it, Adrianne, just get over it.’ And all these things: ‘He’s just doing these things, that’s how these people are.’”

This confused Smith even more. “Like, what does that mean, ‘these people’? Like, people with brown skin? People who can’t speak English as well as you?”

The incident with the maintenance worker still bothers Smith to this day.

“It’s as if me coming out of her meant nothing,” she said.

She said her mother also speaks unnecessarily slow to black family members on her father’s side and friends’ parents with foreign accents. She remembers both her and her sister being frustrated growing up because of it.

Not uncommon in mixed families, Smith’s skin tone versus her older sister has also shaped her upbringing and identity.

“It’s interesting, she’s actually significantly lighter than me,” said Smith. Growing up, her sister was often made fun of for being “white.”

She thinks their difference in skin tones have affected them.

“Our skin tones are constantly commented in a pair. Like, ‘Adrianne’s dark and Makayla’s light.’” Even activities like going to the beach remind her of this, when Smith turns much darker than her sister in the sun.

Growing up, they also had very different social circles. Smith attributes this to their different environments: Smith went to a public high school in Boston where most of her friends were mix-gendered people of color. Her sister went to a private, all female, predominantly white Catholic high school, where a lot of her friends were white women.

However, people falsely attributed the different friends groups to the sisters’ respective skin tones. “It was literally just our circumstances that put us there, but it was almost accredited to the fact that she was lighter than I was,” said Smith.

All this has affected her outlook on racism.

“I don’t believe racism will ever really go away,” said Smith. Despite progress due to the current Black Lives Matter movements, she believes society is too selfish, competitive and focused on comparison, and there will always be some form of discrimination.

“If you want to be the best, there has to be something that’s lower. So there’s always going to be a different standard.” Smith mentioned colorism, which is the discrimination of people of color amongst themselves. She said the common idea of a future where everyone will eventually interbreed and be some shade of brown would not eradicate racism.

“So you hear these things, and you’re like, ‘Hm, okay. So when we get there, then what? Is that the standard of racism is over?’ No. That’s just when other things kick in. Then it’s literally all about shades. We have all these arbitrary lines of what is black and what is white and what is other. Obviously, those are all shady,” she said. And if skin color is not the basis for discrimination, she said, it would be something else, like hair type or eye color.

“For most people they can seem like gray lines, which they are. For others, it’s just hardened fact.”

‘Talitha koum’

Besides attending Church of Christ in Chicopee on Sundays, Smith is also an alto singer and vice president of the UMass Gospel Choir.

“I don’t think I’m good, I just like to sing,” she said.

She also attends Bible study on weeknights with the Cornerstone Christian Fellowship Club on campus.

To still get her “fix” of being around animals, she works at the barn for a few hours a week. It is goats and sheep instead of primates, but she said, “It’s enough.”

Smith’s family is not devoutly religious, so her relationship with God came her sophomore year of high school when she began reading the Bible on her own. One of her favorite books is John. Her favorite story, which she wants to base her future tattoo on, is in Mark when Jesus raises a girl from the dead.

As the (abbreviated) story goes, Jesus is traveling and comes to the house of a man desperate for a miracle. The man’s daughter is dead, but Jesus says, “The child is not dead but asleep.”

Jesus says to the seemingly dead girl, “Talitha koum!” which means “Little girl, I say to you, get up!” This is what Smith wants her tattoo to say.

“When I think of that story, I think of me as a little girl and how there are times when I can be spiritually dead,” she said. When things seem hopeless, Jesus still cares and insists, “She’s only sleeping.”

Sarah Gamard can be reached at [email protected].

Bob • Dec 8, 2015 at 6:01 pm

” I have nightmares about my nonexistent unborn son getting shot, murdered and killed” I hope this person gets the help they need. What a way to go through life. Lots of anger and she seems to know it all, as evidenced by badmouthing her own mother, about how she lives her life. It must be great to have all the answers, without much education or experience.