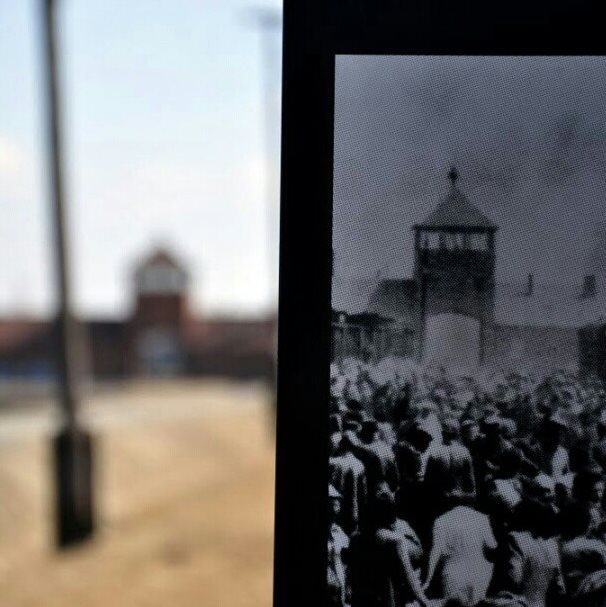

This past Saturday marked International Holocaust Remembrance Day, a day dedicated to remembering, acknowledging and paying tribute to the victims of the Holocaust. Passed in the form of a UN resolution in November 2005, the day was meant to commemorate the liberation of Auschwitz on January 27, 1945. In addition to the commemoration of the event, the resolution also outlines the importance of the day as a tool to educate and inform others about the Holocaust in order to prevent a future one. This is not only fitting and gracious, but also fundamental to the process of such education. However, if the goal is to educate the world and others about the horrors of Hitler’s Europe and the millions who paid the ultimate price in the process, then the education must take place in stages and not in sound bites.

If social media is as much a part of your life as it is mine, you will find slogans and hashtags on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram bearing the words “#WeRemember” and “#NeverAgain.” While these statements were posted with well-meaning intentions, the act of posting these hashtags on social media diminishes the weight and gravity of the Holocaust as both a singular event, as well as a universal tragedy of human history. Scrolling through Instagram feeds and looking at photos of solemn faces, each holding up signs all saying the same thing, confines the history to status symbol. Moreover, whatever moves someone to “remember” in this way obstructs the educational process by confining the act of remembrance to the day itself, instead of using it as an opportunity to further educate oneself on the subject.

The vast majority of those who take place in this campaign of remembrance do not remember the Holocaust because it is history that preceded their time. Although my reservations about the campaign largely speak to the problematic principles behind the act itself, on a more basic level, the words within the hashtag are misconstrued. How could we ever forget if there is an annual commemorative holiday?

There are countless answers to these questions that come in a variety of forms and extend well beyond the length of this column. The subject of the Holocaust as not only living history, but as living memory is a topic of continued fascination. The power of the witness to shape our understanding of the events themselves acts as a temporary privilege for the millennial generation. To serve and to aid the soldiers of living human history, the survivors themselves, is to bear witness to the witnesses. To take part in this process not only does justice to the survivors, but also illuminates their experience, allowing their stories to endure. Such education is more important than ever, especially as we see echoes of Nazi ideology in today’s political life. For example, the

A component of the UN resolution’s original purpose is to use this moment in history as an opportunity to further educate. If throwing up a hashtag in the hopes of getting likes qualifies as a necessary component of the educational process, then so be it. But it seems to suggest something else. With various social media platforms blurring the lines between friends and fans, it is hard to decipher one’s motivations behind such a post. While it is perhaps cruel to say that the act is purely selfish, it is hard to properly discern the reasons for the post when looking beyond the person being pictured. We understand you remember, but what are you doing to ensure that future generations remember?

If the day of remembrance is used as a launching pad for continued learning and education, then the annual moment is serving a purpose larger than itself. If the day serves to signify nothing more than a mere sound bite of a much larger story about the single worst event in human history, then there is something problematic taking place with this process of remembrance. Elie Wiesel is famous for saying, “The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference. The opposite of art is not ugliness, it’s indifference. The opposite of faith is not heresy, it’s indifference. And the opposite of life is not death, it’s indifference.”

Such sentiment continues to hold true today where apathy is the unfortunate substitute for anguish and indifference trumps despair. If we wish to live in a society that sticks to its principles of remembrance and “never again,” then the stories and symbols of suffering and survival will be used as tools to foster further dialogue and education, not slogans and sound bites.

Isaac Simon is a Collegian columnist and can be reached at [email protected].