Why are the men we hail as geniuses so often unrepentant, vicious pricks? More to the point, why do we take their misanthropic behavior as evidence of their dedication to their craft, rather than a reflection of their fundamental unpleasantness?

There’s a bottomless well filled with this kind of man—it’s virtually always a man. We call them “wunderkinds,” “prodigies” and “visionaries,” and maybe those labels genuinely apply sometimes—though I personally wouldn’t say Woody Allen’s filmography is worth preservation. Rarely, though, do we refer to these types by the label that they most deserve: insufferable pieces of garbage. Sure, he can paint a pretty picture. Sure, the way he strings together words in a sentence is rather quaint. Yet, who cares about talent when that body of work was built on the terrorization of others? What kind of ethical framework do we live under if we pretend as if a pretty nature shot that follows the “rule of thirds” is somehow worth more than the lives of the crew that were jeopardized in order to get it?

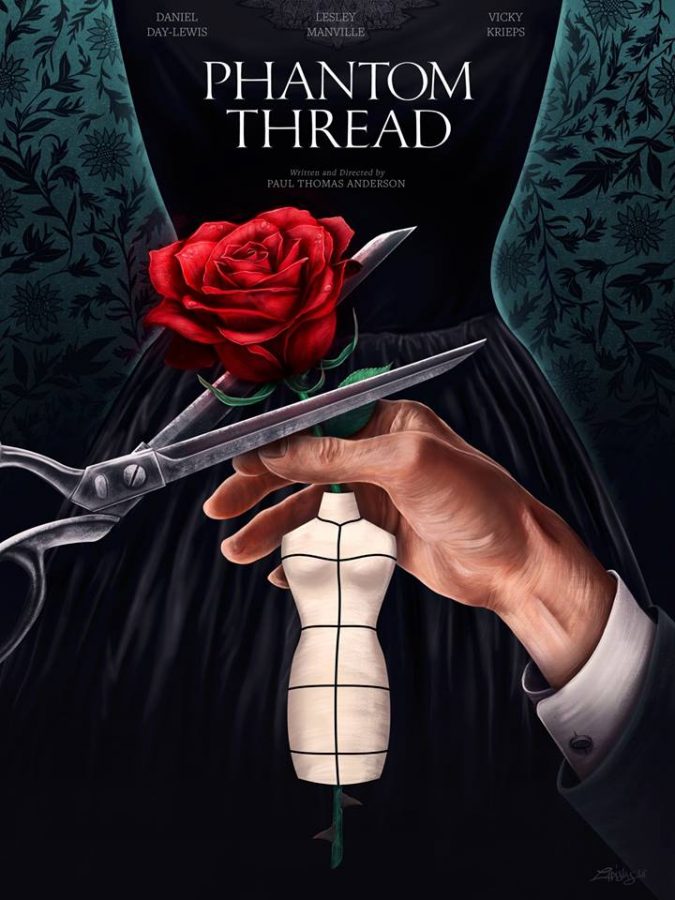

Paul Thomas Anderson isn’t one of these men, but if “Phantom Thread,” his absolutely sublime recent film, is of any indication, he’s terrified that he might become one. It’s a self-reflective piece (come on, the fact that the film’s initials are “PT” can’t be a coincidence), yet it never veers into solipsism. Far from it, “Phantom Thread” is a film that cherishes the necessity of human interaction and castigates the arrogant, asocial tendencies common to the tropes associated with the so-called “tortured artist”—and the misery this fantasy inflicts upon those who buy into it, to boot.

Set amidst the backdrop of the 1950s London fashion industry, “Phantom Thread” centers itself around the love affair between internationally-celebrated dress designer Reynolds Woodcock (an absurd name, even by British standards, chosen intentionally to pop his bubble of self-importance) and plucky French waitress Alma Elso (Vicky Krieps). They meet at the cafe where she works, where Woodcock orders what sounds like half the menu and waits to see if Alma remembers it all. Attracted to the enigma that surrounds “the hungry boy” (a jawline that could cut iron probably helps), Alma accepts his dinner invitation.

It’s impossible to discuss Reynolds Woodcock without discussing the career trajectory of the man who plays him: Daniel Day-Lewis. Famous for his dedication to method acting (to the point where Liam Neeson refused to be around him on the set of “Gangs of New York” because he found his refusal to break character so obnoxious), it’s easy to view the (last!) performance of Day-Lewis (who helped Anderson co-write the film) as consciously self-reflective, as Anderson is behind the camera.

Woodcock’s soft-spoken wounded soul schtick is hard to resist, so of course dinner leads to an invitation back to the private estate. He asks her for her measurements and, via the absolutely exquisite cinematography one comes to expect from Anderson movies, we see him paw his way across her body through intimate close-ups. She is measured. Sized up. Assessed. It is a scene that maintains the illusion of tenderness, but all the red flags are there woven beneath the fabric. Alma’s discomfort is visible, but she pushes it to the back of her mind.

Alma gradually begins to adopt Woodcock’s many nasty traits. It is a means of survival where she believes that she will “win” this game by fighting Reynolds on his terms. There were moments at my screening where Alma throws Woodcock’s poisonous jabs that caused the audience to laugh or cheer. Alma desperately wants both independence or intimacy, but Reynolds is too selfish to grant it to her. In a relationship where meeting each other on equal terms is impossible, it becomes a game of constant flux where the only chance at personhood is to tear the other down to the point where they are lower than you.

The marketing of “Phantom Thread” paints it as a romantic period piece, but in all respects, it’s a horror. What makes the film particularly terrifying is its familiarity, the way it portrays the banality of daily emotional terrorization and the gradual collapse of a relationship to the point where the aggrieved is whittled down into a little nub. Alma and Woodcock’s abusive dynamic does not consist of the stereotypical image of the sweaty guy in the wifebeater who smacks his girlfriend after downing a pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon. What’s terrifying about Alma and Woodcock’s relationship is its codependency—both need the other, and they are all the sicker for it.

Does Reynolds have a passion for his craft? No doubt, but what the film wants to interrogate is precisely *why* he is so passionate. Here is a man whose mother—his primary frame of reference for how to give and receive love—died at an early age. Reynolds’ obsession with his work and the absolute minutiae of his daily life—to the point where he throws fits if any part of his strictly regimented schedule is even slightly thrown out of balance—acts as an extension of his obsession with power and control.

“Artistic types” often mistakenly conflate love with adoration. They want that critical acclaim, that widespread celebration, because it fills the void of abandonment left in their hearts. They desire the affection of a mass group of strangers distilled into a singular body because it acts as a simulation of a real intimate relationship; it provides access to the power they feel was denied to them by their emotional vulnerability.

But try as one might, the artist cannot substitute the approval of ‘the masses’ for real meaningful moments, for they are in love with the idea of Reynolds Woodcock, not Reynolds Woodcock himself. This chase never heals the wounds left inside of them. It only reinforces their sense of isolation, and they lash out against the people who actually do care about them. The problem behind this pathology is simple and speaks to the origins of all the abusive male ‘geniuses’ listed above: ‘brilliance’ is power.

Alma says she wants to give Reynolds “every piece of her.” At the screening I attended, the audience broke out in “aww’s,” but Anderson gradually reveals why they should have recoiled in terror. You cannot fill the deep-seated agony within your loved ones by allowing them to absorb your essence. You’re not tending to their wounds, they’re using you as a crutch. The tragedy of the film: the great mistake people make when they attempt to mend the wounds of those they care about is that they assume that “filling” a void is the same as healing it. The scariest thing about the film is that Reynolds and Alma believe they have been healed—that’s what makes them doomed.

Nate Taskin can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @nate_taskin.

John aimo • Feb 17, 2018 at 5:42 pm

The movie was incredibly boring and over-rated. I give it 1/10 stars.