I always wondered why authenticity is paramount to hip-hop. It sounds silly to ponder since you would think we all would expect a certain level of authenticity, but I never got the notion from fans of pop, country, rock or R&B that they demand as much openness from their artists.

I don’t believe music is just entertainment. Both scenarios bother me equally because art reflects reality or at least is supposed to, and, being someone who isn’t a casual music fan because I’ve invested time and money into the artist, I want to know that what’s being said is true.

Is this our fault for having these expectations? Is it the artist’s fault? Do we have unrealistic expectations for people we don’t know but feel we know because of how attached we are to their art?

Hip-hop originally comes from the street. Often from pain, despair, poverty, struggle and sometimes violence and crime—aspects of life that are not commonly documented in most popular genres of music. So, when we hear our favorite rappers speak about these topics in their music, we can relate. This is why it’s almost as if tragedy is hip-hop’s defining characteristic.

Drake will forever have an asterisk on his legacy after the summer of 2015, when Meek Mill, in a barrage of late-night tweets, accused Drake of having a ghostwriter after discovering Drake didn’t write his feature on Meeks’ “RICO.” This led to Drake releasing the diss track “Charged Up” a day later and “Back to Back” four days later.

What does any of this even mean? So what if your favorite rapper isn’t writing any of their music? So what if the life portrayed isn’t real? I often wonder if a rapper whose music glorifies their violent and criminal past is just as harmful as a rapper who glorifies a lifestyle that they’ve never even lived.

On one hand, an artist with a credible street history can glamorize the fruits of their supposed lifestyle—all while leaving out the harsh realities of crime such as imprisonment and threats of violence that they and their loved ones may face on a regular basis. On the other hand, an artist perpetuating a false image can glorify the criminal lifestyle that they’ve never lived while there are people in the streets risking their lives daily doing the things these rappers make millions of dollars talking about.

Back in December, frontman of the storied hip-hop band The Roots and one of the greatest rappers of all time, Tariq “Black Thought” Trotter, performed one of the greatest radio freestyles in rap history. At New York’s Hot 97 on the legendary Funkmaster Flex show, a staple in hip-hop for radio freestyles for over two decades, Black Thought delivered his freestyle that eight months later people are still unpacking.

Over the classic Mobb Deep “The Learning (Burn)” instrumental, Black Thought amidst common rapper boasts was able to touch on everything from his mother’s drug addiction, growing up in Philadelphia in the 1980’s and being a member of a Grammy-nominated hip-hop band, The Roots. In 10 minutes of near perfect rapping full of quotable lines, one line stood out to me the most. “How much more CB4 can we afford? It’s like a Sharia Law on my Cherie Amour.”

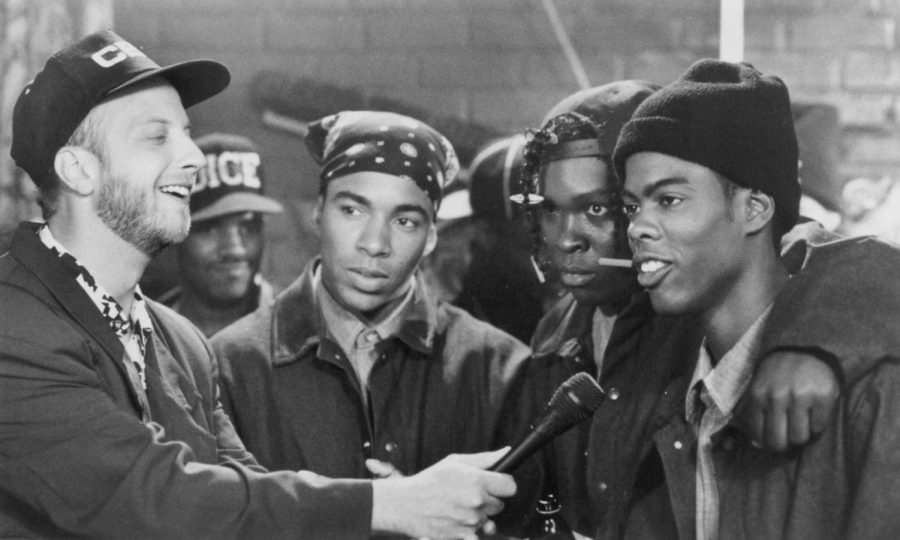

To understand that line, one would have had to have seen the 1993 comedy CB4, starring Chris Rock. Rock’s character Albert is an aspiring rapper living in the fictional Locash, a working class predominantly-Black Los Angeles area suburb. Albert and his friends who also rap try their hand at different sub-genres of the era until Albert devises a plan he feels will change the trajectory of their lives and careers.

Albert decides to steal the identity of Gusto, a local crime boss to achieve instant success in the rap game using Gusto’s gangster persona in an era of hip-hop where “gangster rap” was becoming lucrative. This happens after Albert and his group fail at every gimmick in the book of contemporary rap cliches and try to land a performance at Gusto’s club. Albert meets with Gusto at his club in the middle of a drug deal, and shortly after Albert’s arrival, police raid Gusto’s club and arrest Gusto along with his organization, leading Gusto to believe Albert set him up.

Albert becomes “MC Gusto” while his friends Euripides and Otis become “Dead Mike” and the latter “Stab Master Arson” forming the group “CB4” (Cell Block 4). They rapidly became one of the biggest rap groups in America due to their controversial, violent and sexually suggestive subject matter that isn’t true to who they really are.

Likening faking the funk in hip-hop to Sharia may be problematic. There’s a false notion created by many people in the Wester that Islam is trying to impose itself onto American society but, at the same time, I also appreciate a great analogy in rap regardless of how politically incorrect it may sound.

It’s clear Black Thought feels the way many elder statesmen feel about the current state of hip-hop. Imagine you grow up loving hip-hop so much to the point you want to become an MC. You become an MC and as you begin to improve as a lyricist from years of perfecting your craft, you become popular for your abilities and secure a record deal along with success.

After becoming a successful artist who’s never felt pressured to be something you’re not in order to generate more revenue, you begin to see your peers becoming successful, in some cases more successful than you for portraying an image that isn’t them. It would feel like a Sharia Law on your Cherie Amour, a reference to the 1969 Stevie Wonder hit of the same title describing a woman that he loves. Better yet, an attack on what you know to be “real” in hip-hop, and that can mean a multitude of things.

This is not the first time Black Thought critiqued the current state of the culture. In the video for The Roots single “What They Do” off their 1996 album Illadelph Halflife, he gave The Roots parody common images of “gangsta rap” videos of the mid-1990’s. A time when hip-hop went from being considered a fad to a billion-dollar cash cow, making artists and executives wealthy.

Rapid commercialization of the genre led to a certain level of materialism and display of wealth in the music and music videos. This is mocked by The Roots in scenes such as when the band is sitting poolside sipping champagne around women dancing in bikinis, Black Thought sitting on a bed with three women behind him (a direct mock of the Notorious B.I.G. “One More Chance” video) and the classic wide frame shot of the luxury vehicles lined up next to each other in the project parking lot.

Of course, the artist who does these things needs to be held accountable for their actions, but we also have to attribute fraudulent behavior in hip-hop to the record labels who endorse it. If you sign a recording contract after a record label pursues you because they love your music and image, you would think that the label would want to continue with what they already liked about you and improve it. That is not always the case.

Many industries abide by the “If it ain’t broke don’t fix it” business model. So why would that not be applied to the music industry? Whatever is the most lucrative trend in music is most likely what record labels are going to encourage an artist to do. So, if that means “popping pills” and “sipping lean” is popular then you better believe that will be encouraged to include that in your subject matter.

For decades, the music business has been run by wealthy white men who have no cultural connection to the Black artists who they capitalize off of. This is nothing new. Black people have been one of America’s greatest assets and our experiences have and still are one of America’s main sources of entertainment dating back to minstrel shows of the 1820s that lasted up until the 1960s.

These shows reinforced harmful stereotypes about Black people during and after slavery that we were lazy, dumb and hypersexual, so it’s not a coincidence that record labels push content that in many ways that extend the life of these sets of beliefs.

You may not even live the life of a recreational hard drug user or be in the club every weekend. You may not even be a drug dealer, criminal and womanizer but you may have gotten to a point in your career where that’s worked for you more than subject matter that’s reflective of your life, but now you’re in too deep.

Imagine if a rapper decided that they were going to hold a press conference revealing who they really were in on live television in front of millions of people and said, “No I’m not this person who I’ve depicted my entire career. I’ve never sold drugs, I’ve never shot anyone or owned a gun. I don’t party, smoke or drink.” I feel like if this did happen, depending on the artist, the majority of their fanbase would give them a pass and make excuses for them.

Die-hard fans of artists like Kanye West and Nicki Minaj excuse erratic semi-psychotic behavior when they go on rants that no one understands and say problematic or offensive things. Drake fans stood by him after reference tracks for songs off of his 2015 album “If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late” leaked, revealing that he had assistance writing his raps.

Of course, I know Drake having co-writers isn’t equivalent to faking an entire career (though it depends on who you’re asking).

It’s clear that the powers that be are responsible for the popularity of negative images in hip-hop for monetary gain. This taints authenticity with no regards for the artists and their listeners. At times it does at times feel like hip-hop is under siege by MC Gustos, but if we’re not the ones in charge of what becomes the norm, it’s hard to tell how much CB4 we can afford.

Akil Pinnock can be reached at [email protected]

Prof. Shabazz • Nov 8, 2018 at 10:48 am

I found Bro. Akil’s article to be poignantly illuminating of a problem that all artists confront–the pressure to achieve success even if it requires you to represent something you are not or may be but know that it is not something you are anyone should uphold. It is a dilemma musicians in R&B, Rock, Country, perhaps every type of music may be faced with as an industrialized, corporate-dominated business driven by profits tells the artists what audiences want and demands they produce music that is “violent, trashes women as ‘hoes’ and ‘bitches’, promotes crime and selling drugs,” etc. or not get the lucrative recording contract. I like a song like “I’m All the Way Up,” by Fat Joe, Remy Ma ft. French Montana & Infared. Jogging, working out, the sound get’s me all the way up in my endorphins pushing myself beyond yesterday’s limit. Now, the lyrics are garbage. Nothing said there resonates with me, my life, or my fantasies AT ALL. Thus, I share in this article’s wish that audiences could get better from the industry and the Clear Channel owned radio stations. Take Prof. McBride’s class and keep up the good work.

amy • Nov 4, 2018 at 5:57 pm

I found this article entertaining. It’s trying to take rap/hip-hop music most of which is violent, trashes women as ‘hoes’ and ‘bitches’, promotes crime and selling drugs as something respectable or serious. It’s hilarious.

Prof. Nick McBride • Nov 4, 2018 at 4:31 am

Is Rap Journalism or the great American Novel? The best literature is based on fact. Journalistic facts are historical record. Rap is Truth. Chuck D said Rap is the CNN of black America. I don’t know anything for certain. Socrates and Confucius agree with me, or I agree with them depending how you frame it. I know this for sure. This is a tremendous piece of contemplation you have laid out Akil. Your future in music writing is unlimited. I do have a selfish motive. My Music as History Politics and Metaphysics meets on Tuesday evenings. Register for it. Your peers and I, need your contribution.