I’m still pretty mad about the 2014 Grammys.

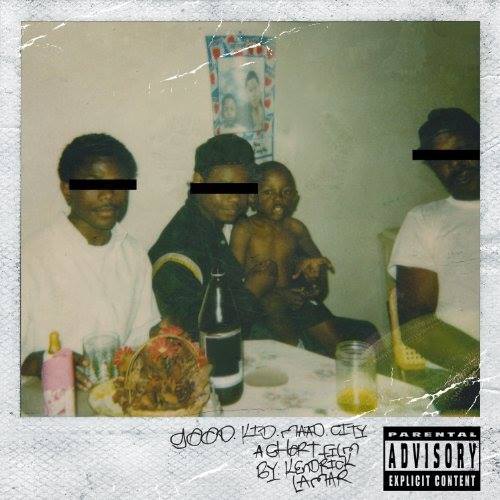

As far as I was concerned, both the Album of the Year and Rap Album of the Year categories were no-brainers: Kendrick Lamar’s major label debut, the incomparable “good kid, m.A.A.d city,” was the best album of that year by such a stretch, it was hard to imagine any other result.

I found a way to stomach Daft Punk’s “Random Access Memories” taking Album of the Year — maybe I just don’t understand that genre of music, and I hadn’t really listened to that much Daft Punk — but Kendrick losing out to Macklemore’s “The Heist,” as much as 15-year-old me liked Macklemore, is a blatant music award travesty.

Kendrick’s sophomore album turned six years old last week, and it’s an album I still listen to, in some proportion or other, on a near daily basis. It’s one of three albums I have downloaded on Spotify to listen to if I’m ever without service, and it never fails to surprise me with its brilliance.

Its top-notch production, consistently excellent flow, and, most importantly, its thematic scope and lyrical density make “good kid, m.A.A.d city,” as far as I’m concerned, the greatest hip-hop album of all time. It explores so many themes — race, gang violence, addiction, relationships, prostitution, objectification, economic disenfranchisement, the list goes on — with incredible deftness.

A concept album at its core, “good kid, m.A.A.d city” tells a story in a way that very few albums do. It’s not a collection of songs thrown together in a playlist — it’s a deliberate, cohesive and moving story.

The album details Kendrick’s coming-of-age in the heart of Compton, California, and his experiences with the Pirus, a Blood-affiliated street gang in the city, that shaped his teenage years.

The album’s plot is driven not only by the music, but the skits and voicemails at the end of each track that tie everything together. It actually opens with one of those skits — a group of boys reciting prayer, which comes up later — and transitions into the album’s lighter tracks, “Sherane a.k.a Master Splinter’s Daughter” and “B—-, Don’t Kill My Vibe,” which sets up Kendrick’s relationship with Sherane and the ensuing beef that surfaces in the darker parts of the album later on.

Darkness begins to creep into the story on “The Art of Peer Pressure,” as Kendrick raps about the crimes he starts committing with his friends — robberies, mainly — as a light opening turns ominous about a minute into the song. He tells the story of these robberies at length, and explains how he got sucked into all of this, as the phrase “I’m with the homies” appears seven times. “Usually, I’m drug-free, but s—, I’m with the homies,” he explains at the end of the first verse, and “that’s ironic, cause I’ve never been violent/Until I’m with the homies,” at the end of the second.

“The Art of Peer Pressure” leads into “Money Trees,” which has been my favorite song on the album since I was 13. It takes almost a hopeful turn, as Kendrick waxes poetic about the ambitions of every Compton hustler, while summarizing the events of the album thus far. On its own, “Money Trees” takes on economic disenfranchisement and the harsh realities of growing up in Compton poverty, temptation and faith — the hook’s first lines are “It go Halle Berry, or hallelujah/Pick your poison tell me what you doin’,” — on a track that can be at times haunting or uplifting.

“Money Trees” even confronts the immortalization of victims of the violence, including Kendrick’s uncle — “Everybody gon’ respect the shooter/But the one in front of the gun lives forever” — and features a brilliant guest verse from Jay Rock, who touches the financial dreams of every kid on the street, “dreams of me gettin’ shaded under a money tree.” It closes with one of the funnier voicemails of the album, as Kendrick’s mother is trying to get him to bring her van back home — as she has been since the outro of the first song — with her husband drunkenly serenading her in the background.

“Poetic Justice” is a fun track that asks one of the album’s deepest questions: “If I told you that a flower bloomed in a dark room/Would you trust it?” This line has been dissected to such length that I couldn’t really even get into it, but I’d encourage you to visit the song’s Genius page to read several different interpretations.

I think the entire album can be summed up by the tracks “good kid” and “m.A.A.d city.” That’s what Kendrick is, after all: a good kid — a straight-A student, a kind soul at heart — who is caught in the madness of a city like Compton. “m.A.A.d city” has always felt to me like Kendrick’s most cathartic song, as he cuts loose on a “trip down memory lane/This is not a rap on how I’m slingin’ crack or move cocaine,” a more intense detailing of the violence. It also features another strong guest verse, as MC Eiht, another Compton-based rapper, details his own experiences in the city after a mid-track beat switch.

The album’s overall plot is woven through every track, and by the time “Swimming Pools (Drank)” rolls around, Kendrick’s buddies are determined to exact revenge after he was jumped at the end of the first song when he rolled into the wrong part of town, and their plan’s coming together. “Swimming Pools” takes a deep dive into the alcoholism and addiction that consumed members of his family — and, at times, himself— before the track’s skit sees the album take a dark turn, as the plan backfires and Kendrick’s friend Dave is killed in the shootout.

I’ve always seen “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst,” as the album’s hidden gem, and by far the most lyrically dense of any Kendrick song. It’s really two separate songs with an interlude, and comes from several different perspectives. He approaches life in Compton from a few different angles, including Dave, who aspired to be a rapper himself and was killed over a senseless beef, Keisha’s sister — Keisha was a prostitute who was murdered in a track on his first album, “Section.80” — who also fell to a life of prostitution, Kendrick himself and Dave’s brother, who has a meltdown after the death of his brother.

A skit is cut into the middle of the 12-minute song, as Dave’s brother screams that he’s “tired of this s—! I’m tired of running, I’m tired of this s—! My brother, homie!” The track goes dark in the back half, as Kendrick says he’s “dying of thirst,” realizing this life is unsustainable. He says he’s “tired of running, tired of hunting/My own kind, but retiring nothing.”

The song is so lyrically dense, and as much as I love “Money Trees” and a few other Kendrick songs — “HiiiPower” on “Section.80” is untouchable — this is his masterpiece, his magnum opus. It tackles several different themes on its own, and ties together Kendrick’s entire experience in Compton. The boys realize the senseless of what they’re doing, the pointlessness of the violence.

In the final skit, Kendrick’s neighbor, an older woman asks why they’re so angry, and eventually convinces them to accept Jesus into their lives, reciting a prayer and telling them to “remember this day/The start of a new life — your real life.”

Three more tracks tie things together a bit more, but “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst,” in all its brilliance, is the end of Kendrick’s journey. He’s gone from enjoying life on the streets, getting high and committing robberies with his buddies, concerned only about material things and street cred, to a deep realization of his situation. He begins to understand the madness he’s been drawn into, and the urgent need to escape.

You can consider “good kid, m.A.A.d city” to fall into the gangsta rap category, but it has a very important distinction — Kendrick doesn’t glorify the experience. He sets it up that way early on, but shatters that image and all of its misconceptions in the latter half of the album, presenting a brutal, accurate representation of the lives of inner-city youths from Compton to New York and everywhere in between.

I’ll be the first to admit that “good kid, m.A.A.d city” doesn’t have the sort of tracks you’d hear at a frat party or the popularity and replays of some Drake singles or Kanye songs, but its brilliance goes far beyond that.

The genius of “good kid, m.A.A.d city” resides in its cohesive storytelling, its broad thematic scope, its incredible lyrical density and its brutal, unflinching honesty. Kendrick’s sophomore album is an incomparable concept album, and six years later, it remains as groundbreaking and remarkable as it did on day one.

Amin Touri can be reached at [email protected], and followed on Twitter @Amin_Touri.