In the decade following the Sept. 11 attacks, Senate investigator Daniel J. Jones spent seven years combing through over six million pages of classified CIA documents, exposing inhumane torture tactics used by the United States government against 119 people presumed to be terrorists.

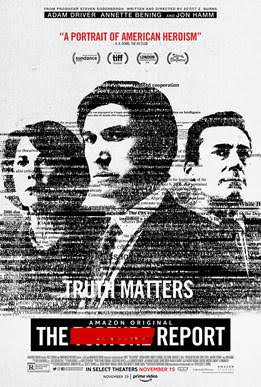

Jones’ groundbreaking findings, concluded in a 6,700-page report and a 525-page executive summary in 2014, are brought to the mainstream once again in the docudrama “The Report,” written and directed by Scott Z. Burns. Both men sat down with college students in Boston in early November to discuss the film.

From shaving prisoners’ beards to waterboarding them for hours on end, the CIA employed tactics kept under wraps to the public in an effort to extract intel, believing that their work would prevent future attacks. Burns, after researching these tactics in Jones’ report, was shocked to hear that his own country’s government would use such violent methods to force potential terrorists, some who weren’t proven to be affiliated with terrorist organizations, to talk.

“The revelation… that torture does not work as an interrogation technique and never has,” Burns said, “and that the CIA went down this road anyways is staggering to me, and I wanted to understand the answer to that question.”

Throughout the 118-minute movie, the audience gets a front-row seat to the seemingly insurmountable obstacles that Jones (Adam Driver), a staffer for California Sen. Dianne Feinstein (Annette Bening), must overcome as he unravels dark secrets that the government has fought to hide. From “relocating” classified CIA documents to facing potential imprisonment, Jones’ life was consumed by the investigation.

Although his resemblance to the real investigator was questionable, Driver’s portrayal of Jones was, according to Jones himself, accurate to his real life demeanor: focused, driven, straying from the spotlight. Driver and Jones may be physically unalike and come from different backgrounds but, like many decisions made throughout the movie, the decision to cast Driver was from Burn’s intuition.

“The thing that made me very excited to work with him is he felt he had some awareness of the story and yet when he read the script, he became of how little he didn’t know, and that made him curious,” Burns said. “I said curiosity is what I want to be the kind of motor for this character. He’s got to be someone who wants to find out more.”

Aside from Driver’s approach to the script, it was his practice at The Juilliard School in New York City and experience in the Marines that meant, “he understood chain of command, he understood protocol, and that was also going to be very important because the Senate has all of those things and a Senate staffer can’t just come in and beat on the table and throw things around,” Burns said.

Despite being the main character, there were few moments in the film that centered on Jones’ personality. Jones’ only outbursts came during impassioned speeches to Sen. Feinstein, keeping true to the investigator’s personality.

“I’ve known that it’s not my story, this is a story about the report itself,” Jones said. “It was very accurate — that I was focused on the work for seven years. And there’s a scene talking about being a neglectful partner, and I was a neglectful partner for that period of time.”

Jones credits the attention to detail to Burns’ own drive to get the facts right. As the investigator talked to various journalists and academics following the release of the report, he noted how the majority of people would ask for major conclusions in the case. Solely understanding the big picture wasn’t Burns’ objective.

“He was calling about footnotes… so really our relationship began, for lack of a better word, ‘nerding out’ on the material,” Jones said.

As filming progressed, Jones watched from the sideline, understanding that the movie wasn’t his to direct. After all, the studio that controlled the movie before Amazon Studios took over cast Jones aside and wouldn’t take his consideration into the making of the movie at all, he said. Burns “made choices I’m very proud of,” Jones added, trusting that the director would tell the story responsibly.

Burn’s incisive storytelling abilities didn’t begin with this film — he has tackled difficult narratives as seen in his writing for “Contagion” and a more recent production, “Laundromat”. Burns was able to capture the monotonous lifestyle of Jone’s while still providing the viewer with comedic relief.

The comedic relief stems from the two characters, James Mitchell (Douglas Hodge) and Bruce Jessen (T. Ryder Smith). The duo are psychologists with military contracts who had worked in a Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) School. Even though both parties had little to no experience in interrogation, the CIA hired them to pioneer an interrogation program for suspected terrorists in the wake of Sept. 11.

Neither man had the background or experience to conduct this program, and as Burns put it, “I also believe from speaking to a lot of other people who are experts in the field of interrogation that these were people who were completely unqualified to do what they did, and they should not have been there, and they did a lot of damage.”

The dynamic between the two characters is laughable. Their credentials come from having Ph.D.s in family therapy and hypertension. To the audience, it’s clear that their interrogation tactics are not working.

There’s a scene in the film that goes in tandem with the ineffectiveness of Mitchell and Jessen’s tactics where Annette Bening says to Adam Driver, “If you have to do it 183 times to get this information, then why do you have to do it 183 times?”

It wasn’t a matter of comedic relief or strategically place jokes, but how Burns put, “things just were funny by chance.”

The title speaks for itself. It’s not very often that a report is compelling. So, why would this particular report be perceived any different? Adam Driver perfectly encapsulates Jones’s trials with the largest systematic study of toruture. Like in the rest of Burn’s films, “The Report” falls right in line, delivering the message home. Jone’s rigor and integrity come to light in this film.

“The Report” isn’t solely a story about Jones’ mental fortitude. It revels in the hypocrisies of the government during the time following the Sept. 11 attacks. Despite the report being halted at every corner by the agency and the White House itself, it doesn’t fail to revel in its actual faults.

As Daniel J. Jones put, “There’s so much cynicism in those institutions right now, and I just hope that this story inspires lawmakers and staff and citizens that this can work, even if it’s not perfect.”

Matt Berg is an Assistant OpEd Editor and can be reached at [email protected] or followed on Twitter at @Mattberg33

Morgan Reppert is the Managing Editor and can be reached at [email protected] or followed on twitter @ReppertMorgan.