In modern times, any claims about the world require one thing: evidence.

One cannot claim the world is flat without proof, nor can one claim it is round without proof. In that regard, the most common theory surrounding the origin of society, dubbed social contract theory, can only be regarded as a myth. Social contract theory asserts that the state formed when people surrendered some of their freedoms to a higher authority in order to preserve their remaining rights. Social contract theory is not only a myth, but it is a violent one.

Unlike the theory of evolution, there is no physical corpus of ancient skeletons to support social contract theory’s veracity. In anthropology, we are taught that stone outlasts wood. Similarly, the lack of clothing in archaeological sites does not imply our ancestors did not have clothing. The same can be said of history: the immense documentation of history does not imply that nothing happened before the documented events.

The origin of society lies in prehistory, since writing sprang from the needs of the early states. That is to say, the beginning of documented history started only after the state was established. For that reason, it can only be regarded as a myth in the same way that the idea that all languages have a common ancestor is a myth: it is unverifiable and not in our historical record.

If the origin of the state is uncertain, what are the alternatives to social contract theory? The deceased American anthropologist David Graeber provides one in his book, titled “Debt”:

“The real weak link in state-credit theories of money was always the element of taxes. It is one thing to explain why early states demanded taxes (in order to create markets). It’s another to ask ‘by what right?’ Assuming that early rulers were not simply thugs, and that taxes were not simply extortion — and no Credit Theorist, to my knowledge took such a cynical view even of early government — one must ask how they justified this sort of thing.”

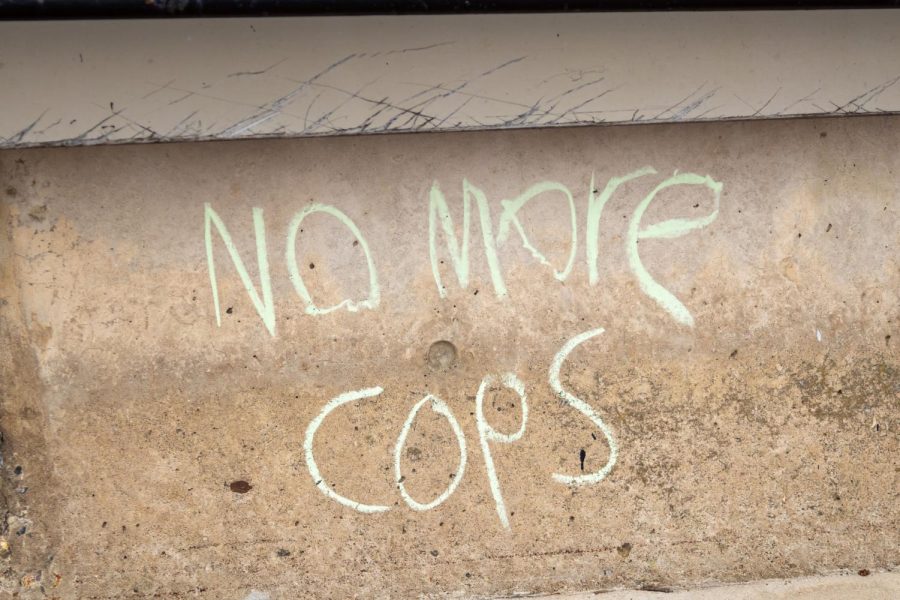

I feel that it is irrelevant to dwell on the veracity of myths. It is more important to understand the structure that it reinforces. Take, for example, the view held by the Chinese anarchists, which can be seen as an inversion of the social contract myth. Where the former myth held the scheme: war (against all) leads to mediation (social contract) which leads to peace (society). The latter held the scheme: peace (peaceful agrarian societies) lead to mediation (subjugation) which leads to (class) war. The lack of evidence for the view held by the Chinese anarchist is irrelevant; it is enough to know that the Chinese anarchists fought against monarchism, colonialism and Confucianism to understand this inversion. In the same way the social contract’s lack of veracity is less important than the structure it reinforces, it holds that only with the surrender of our rights there can be peace and remaining rights maintained. Yet in reality, this is not the case.

Multitudes of peoples around the world can attest that their rights were suppressed by the power of the state and now have a fear of the authorities. As the Irish playwright Oscar Wilde once wrote, “the worst slave-owners were those who were kind to their slaves, and so prevented the horror of the system being realised by those who suffered from it.”

I understood this as saying that to present a false reality is to act in violence. The maintenance of social contract theory thus obscures the true nature of the state, and in that regard, it is violence. Moreover, it is violence to tell people who have been oppressed by the state that their lack of freedoms is because of an ancient vow made by long-dead people in order to protect their rights. And lastly, it is violence to tell people that without the state there will be only war when the opposite is more likely to be true, because of archaeological evidence indicating that war emerged during the Neolithic period, or only around 12,000 years ago. It is an act of violence that obscures a fact, the fact that a better world is possible.

For those who are still undecided about their major, if we at The University of Massachusetts wish to “be revolutionary,” we must discard the long-held notions that many hold as timeless and unchanging. They will only hold us back in our imagination and thus, reality. It is anthropology that can reveal that these timeless notions are just that: notions. For that, anthropology is a science that can be revolutionary.

Benjamin Zhou can be reached at [email protected].