Players chatted familiarly with each other, cracking the usual jokes while sharing stories about their weekends. They awaited the arrival of their coach for what they assumed was a typical recap of their most recent game, a 33-27 win over Rhode Island in their season finale on Nov. 21 of last season.

Junior running back John Griffin arrived at the gym as he did in week’s past, expecting an assessment of his own and the team’s performances amidst analysis of game film.

Yet, something about this meeting seemed a bit peculiar.

On this day, Huskies coach Rocky Hager was not in attendance. Instead, athletic director Peter Roby came prepared to speak to the players about something, alarming Griffin and his teammates that something may be wrong. Perhaps, he thought, this wasn’t going to be a normal meeting after all.

Griffin believed that Hager might have been let go.

After all, the Northeastern football program had suffered six-straight losing seasons.

As Roby entered the gym, the jovial players began getting anxious until they finally found out what this meeting entailed.

Their curiosity mounted and an eerie silence set in.

“I remember it like it was yesterday,” Griffin said. “We were sitting there, everyone was having fun, cracking jokes and when he got to talking, you could hear a pin drop in the basketball court.”

When Roby finally spoke, he revealed that the Northeastern football program had been cut. His message reverberated through the open gym walls and sent waves of shock and disbelief through the minds and souls of the Husky players.

Griffin was reflective, trying his best to digest the unsettling news that he had just heard.

“Some people reacted, some people got up and left,” Griffin said. “Kids were asking him ‘Why?’ I kind of sat back and took it in and listened to what he had to say and seeing how everyone else around me felt, also.”

Northeastern President Joseph E. Auon decided that the university would no longer fund the $3 million dollar program annually. Northeastern agreed to honor all scholarships and any player who transferred maintained his eligibility, yet 87 students and 10 coaches were left without jobs and a place to play football this fall.

The news began to register with each player and initial disbelief turned to disappointment and in some cases, panic.

For some players, football was the reason why they went to Northeastern. The thought of life without it was worrisome.

Griffin’s choice to go to Northeastern was mainly due to its academics, but his passion for football and recent success left him searching for an alternative way to combine the two.

Transferring to a new school would force Griffin to adjust to a brand new setting, schedule and routine. In addition, he would need to learn a fresh system of football, including a new playbook, new terminology and new teammates, but it seemed like the natural thing to do.

Griffin’s stepfather was in the military doing work that demanded his family move often. Having relocated over 13 different times in his life, his adjustment to the Unniversity of Massachusetts was smooth, but not seamless.

With seven other transfers at UMass, including two teammates from Northeastern and three Hofstra players who experienced their program’s demise, Griffin wasn’t the only one needing to adjust.

“It’s a feeling you never forget. I almost didn’t believe it, it didn’t seem like reality,” senior Minutemen wide receiver Anthony Nelson said, a former Hofstra player. “It was heartbreaking, knowing that in a couple more weeks, you have to cut loose and say ‘bye’ to some of those relationships you built with people.”

As one of the leading rushers in the conference, Griffin’s teammates welcomed him, knowing that he would help the team accomplish its goal of reaching a national championship.

Griffin left Northeastern as the fifth Huskie to rush for over 1,000 yards in 2009. He finished with 1,009 yards on 207 carries, a First Team All-CAA performer and member of the 2009 New England Football Writers All-Star Team.

The end of the Northeastern football program brought many suitors to the Boston, Mass., campus, and more who tried to court the star tailback over the phone.

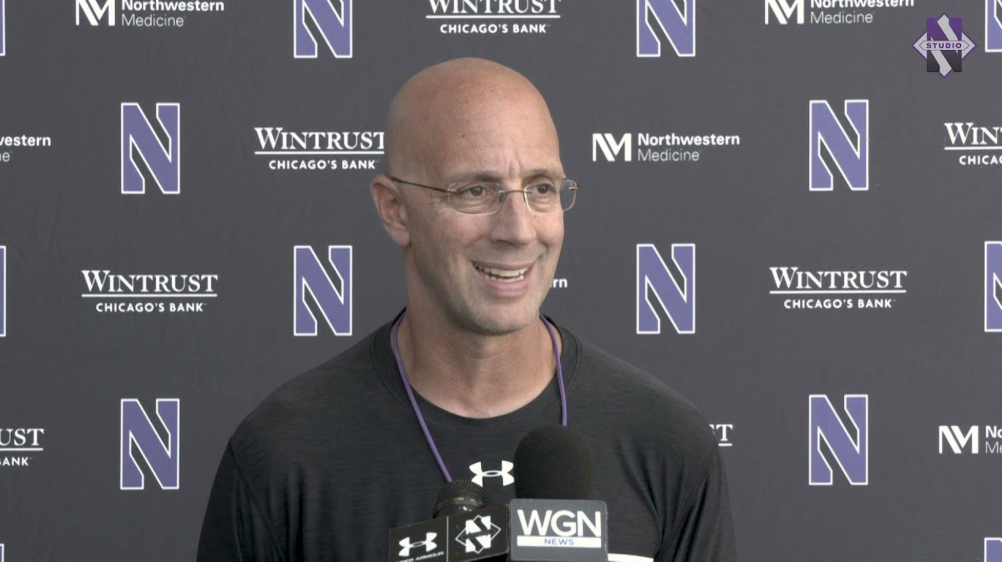

When Minutemen coach Kevin Morris caught wind of the situation, he made sure he was the first to meet with Griffin and his immediacy was a big factor in the coveted player’s decision.

Word spreads quickly throughout the college coaching circle and the rumor was that the Northeastern program might be cut later, while Hofstra‘s decision to cut its program on Dec. 2, came as a complete surprise.

Following Northeastern’s demise came an immediate slew of coaches hoping to court the available players. Within 10 minutes of hearing the news, he made arrangements to go to Boston the following day, which impressed Griffin.

“His actions of being there the next day showed that he really cared and he was on top of it,” Griffin said. “He sat down with me man-to-man and it didn’t really feel like we were talking about college football.”

Griffin also received numerous offers from other coaches, including playing at Football Bowl Subdivision programs, so his decision, though opportune, was that much harder to make.

According to Griffin, anywhere from 15 to 20 coaches met with him in person regarding football, along with another 10 to 15 who spoke with him over the phone. These schools represented the Colonial Athletic Conference, Conference USA, and the Mid-Atlantic Conference, including Miami of Ohio, who made a strong case.

After the two-week open house for Griffin subsided, he sat down and weighed out all of his options.

He spoke with his immediate family, who currently reside in Massachusetts and their proximity was a strong factor in UMass’s favor. He wanted desperately to play at a higher level, but a decision to play FBS likely meant less playing time, which he was certainly weary of.

However, his credits would need to be cleared for transfer before he could decide on any school.

He spoke with his teammates at Northeastern, some of whom decided to stay at the school and finish their degrees and others who were searching for somewhere to play football as well, including senior lineman Greg Niland and sophomore linebacker Chad Hunte.

Niland was always admired by Griffin as a leader and decision-maker. After finding out that two of his teammates were making the move to Amherst, along with the strength of the UMass program and his respect for Morris, Griffin’s mind was made up.

“It’s definitely made the transition a lot easier,” Niland said. “We were going through the same things at Northeastern after the program got cut. It made us a lot closer and it was great to see him here with me and Chad.”

With the conclusion of football season came a disheartening month for Griffin. The Northeastern campus felt unusually cold, even for December. Everywhere he turned, there were constant reminders that he was no longer a Husky football player and he yearned to leave the campus as soon as he could.

He enrolled at UMass beginning in Spring 2010, beginning his acclimation from a big city to a small town.

Griffin lives in Westminster, Mass. and has lived in 13 different places including California, Texas and Germany. He has lived in the hustle-and-bustle of city life and felt the quaint atmosphere of small-town living.

For Griffin, the biggest adjustments were made in his academic life, but even those weren’t anything he couldn’t handle.

“It was different, but at the same time, it was just school with a different atmosphere,” Griffin said. “Putting on the same book bag, going to the same classes, grabbing my pens and notebooks. I’ve been doing it for three years, it feels like second nature.”

The class sizes at UMass are much bigger than those at Northeastern and professors have less time to offer one-on-one assistance to students. Griffin, a sociology major, found it hard to fit in with students whom he felt already had rapport with each other.

Yet, besides the old-fashioned buildings and furniture, Griffin sees nothing different from the education he receives at UMass than he did at Northeastern.

He has classes he enjoys and those he doesn’t. He relates to some professors and not to others.

“If you can work independently and have a knack for going out and finding stuff out for your own, it’s the exact same education,” Griffin said. “It’s not necessarily the education, but how you apply yourself.”

Griffin takes solace in the fact that some of his teammates faced the same adversities, easing his transition on and off the field. The feeling was mutual, shared by the six other transfers on the team.

“At first, it was nice; we all gravitated towards each other because we really didn’t know anybody. After that first week, or so, everyone mixed around with the whole team and there were no ‘transfers,’ only UMass guys.”

When he wasn’t enveloped in school work, Griffin made time to study football, including the new offensive system that the Minutemen run.

He trained with the team in the spring, practicing schemes, learning the terminology and picking his coaches’ brains.

“In the beginning, everything was a little slow, seeing things in live speed,” Griffin said, “but I think it’s picking up for me. The game’s starting to slow down a bit for me.”

“It wasn’t like we had to teach a old dog new tricks,” Morris said. “These guys were ready for the challenge and ready to be immediately integrated into the offense.”

He took after his new teammates in practices, imitating them on field while heeding their advice. He was welcomed by the Minutemen players and was immediately considered a leader on the team as a senior and an experienced player.

Before the 2010 season’s start, Griffin was named to the Phil Steele Second Team Preseason and the CAA Preseason First-Team by league coaches.

Currently, Griffin is the team’s leading rusher with nearly 96.8 yards per game and is on pace to compile over 1,000 yards rushing on the season. He ranks second in the CAA in rushing yards per game and 25th in the Football Championship Subdivision.

Griffin ends his typical day of classes and readies himself for another day of practice. He emerges from the locker room with his bulking shoulder pads, his high socks under his cleats and his helmet in hand.

He walks onto the field turf at McGuirk Alumni Stadium like he had at Oakmont High School, with the same piece of mind he left Northeastern with.

He dons the same focus and determination that he has carried with him throughout his collegiate career, with a national championship in the back of his mind.

He ducks and weaves through his running back drills, coaches preaching ball security per usual, yelling in his ear, “high and tight!”

These football tenets are not things he hasn’t heard before, though they are being taught in a unique way, with different terminology.

While his coaches drill him, he takes it all in, glad to be playing football again and taking things as they come.

Dan Gigliotti can be reached at [email protected].