This summer was a triumph for the queer community, after same-sex marriage was legalized in all 50 states of the United States. However, progress is still due for the younger members of the community growing up in a still-heteronormative America, particularly in the classroom.

A Boston Globe article published in early September explained the recent push in the United States for more inclusive sex education, where the Human Rights Campaign Foundation and Planned Parenthood Federation of America help teachers talk more openly about sexual health issues pertaining to LGBTQ students.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, each state differs dramatically in its percentage of middle and high schools that offer any LGBTQ-related sex education, with Massachusetts in the lead at nearly 44 percent of secondary schools. Nationwide, however, queer inclusivity is wanting. State legislatures in Alabama, Arizona, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas and Utah have even banned positive classroom discussion on homosexuality.

In United States schools, queer inclusivity is statistically wanting. University of Massachusetts Stonewall Center employee and external events coordinator Josie Pinto agreed that there is a definite lack of resources and conversation on the subject. Normalizing LGBTQ identity and providing resources needed at an early age, she said, will help LGBTQ youth become more informed in the decisions they make. Important concepts that need to be discussed in a queer-inclusive format include sexually transmitted diseases, protection and consent.

Pinto, who double majors in public health and social thought and political economy with a minor in women, gender and sexuality studies, believes that LGBTQ students need to put in the effort to independently seek out information about their sexual health and safety. Unsafe sex is common due to a lack of inclusive education, she said. For example, safe sex supplies are often mistakenly dismissed when there is no risk of pregnancy, which contributes to many LGBTQ community members contracting sexually transmitted diseases.

She is not the only one who argues there is a STD epidemic in the queer community. According to the Globe, health statistics and federal findings show that gay and lesbian students, facing pressure to have heterosexual sex, are more likely to have multiple partners, forgo protection, and thus engage in risky behaviors that result in pregnancy or sexually transmitted diseases.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is spending $13 million a year on a five-year HIV prevention program in 19 states, including Massachusetts, that will teach gay and transgender youth about relevant protection methods, the HIV infection rate is rising rapidly for people between 13 and 24 years old, especially among gay youth.

According to the Office on Women’s Health’s website, lesbians and bisexual women are at high risk of extracting sexually transmitted infections partly because they are less likely than other women to get routine mammograms and clinical breast exams, possibly due to fear of discrimination among other factors.

Pinto said that race, class, religion and other factors make it hard to implement change and address the huge public health concern in an academic setting. She argues that schools need to allow youth to feel more comfortable exploring their identities with less pressure to conform to hetero-normative and outdated views. Progress, little as it has been so far, has mainly been seen in college environments because the movements have been student-led, she said. However, not many people are fighting for change within younger environments.

And, to make things more complicated, it’s hard to measure how many members of the LGBTQ community are practicing safe sex. A 2013 data collection from Campus Pride, a national online network, indicates that nearly half of sexually active LGBTQ teens are not consistently using protection, despite many having multiple partners. Hillary Montague-Asp, a graduate assistant at the Stonewall Center, said it is important to note the difficulty in collecting the data, considering sexual self-identification versus behavior and willingness to disclose sexual information. The data is also taken from groups of high school students.

But how far off are college students from the surveyed demographic?

Montague-Asp argued that institutions use the disparity in education as an attempt at exerting moral and social control over sexual and racial minorities, as well as working class citizens, and that LGBTQ-inclusive education will be difficult to teach until queer relationships are normalized and legitimized.

“In current sex education curriculum, there is often as assumption that ‘women’ have certain body parts and ‘men’ have certain body parts,” she said in an email. “Not only is this information incorrect and harmful to transgender and gender non-conforming youth, it prevents those populations from learning safer sex behaviors relevant to their own bodies and experiences, and also prevents people who engage in sexual activities with people of multiple genders (including transgender and gender non-conforming people) from accessing information they need to engage in safer sex behaviors and practices.”

Pinto and Montague-Asp encouraged teaching about identities first, before other components of sexual education, along with sexuality and gender existing on a scale rather than a binary. Encouraging expression of all identities, they contended, will yield major long-term benefits.

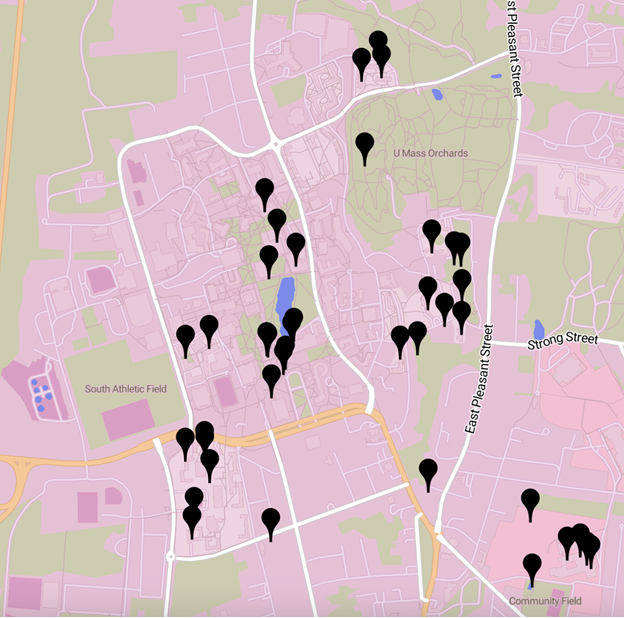

Stonewall, in conjunction with University Health Services, sponsors rapid HIV and STD testing twice a month in the Campus Center. They also supply free, safe sex supplies for people of all genders and sexualities at Stonewall’s office, located in Crampton Hall in Southwest Residential Area, and at many of their events.

According to Montague-Asp, they are now working to provide more outreach, resources and services for asexual students. The organization also provides a variety of barriers and lubricant to be used by people of all genders to engage in safer sex practices, as well as providing referrals to organizations where students can get more information about sexual health.

Ann Becker, registered public health nurse and director of the UMass Medical Reserve Corps, said that an obstacle faced by UHS is making sure LGBTQ students are comfortable. This is why UHS hosted its first-ever off-site testing clinic last Tuesday, Sept. 29 in the Campus Center, modeling the procedure after Tapestry Health in Amherst. Stonewall has helped with advertising.

Becker said UHS has always offered one-on-one appointments with nursing practitioners and physicians, and they continue to do that. However, this is their first STI screening-only clinic. Their goal now is to try to bring in more people to get tested.

Becker advocates using protection and being smart and informed, whatever one’s orientation or sexual behavior. If a student has specific questions or seeks treatment that would require a private conversation, Becker recommends seeing a UHS health provider. She also recommends calling the Center for Health promotion if they seek advice or just someone to talk to.

Becker said, of all demographics, the one that should get tested the most frequently is men who have sex with men, depending on how many partners they have. She said everyone should do a personal risk assessment, which she hopes will soon be put up on the UHS website. A personal risk assessment evaluates sexual behavior, number of partners, and other related factors to determine how much an individual should be tested for STIs and STDs.

The screenings done by UHS in the Campus Center, which will be happening periodically throughout the year, are for asymptomatic students. That is, students who are not showing any symptoms of an STI and voluntarily come to get tested for chlamydia, gonorrhea, HIV and syphilis. If someone is showing symptoms, Becker recommends coming to UHS to see a provider for a one-on-one session.

HIV testing is rapid; the results are given within 20-30 minutes with a finger prick. Chlamydia and gonorrhea testing is done with a urine sample, and results are back within one or two days. Insurance is required for asymptomatic testing.

After searching Google herself, she concurred that finding proper information on LGBTQ-concentrated sexual health online, while it is perhaps the most accessible resource yet, is out-of-date.

“This is quite timely,” Becker said. “We recognize that this is a need on campus here.”

She showed an informational poster affiliated with Get Yourself Tested that featured both stick figure depictions of a heterosexual couple and a homosexual couple. All students, she said, regardless of identity, should get tested at least once. The more partners a person has, the more frequently they should get tested.

The screening room for the rapid testing at the Campus Center was what one would expect: quiet, slightly awkward and full of asymptomatic students bent over clipboards, filling out their risk assessments and health insurance information.

Nurses were helpful, lines were short and the embarrassed tension in the air was not unbearable. A table full of free pamphlets and barrier method devices for students (condoms, dental dams and lubricants) was immediately available at the entrance. No pamphlets were LGBTQ-specific, but none were LGBTQ-exclusive, either. Virtually all had information for STDs and STIs: how they are extracted, how they can be prevented and the protocol for getting tested – information that was relevant and helpful regardless of behavior.

When walking out of the Campus Center Tuesday, a group of Evangelical Christian preachers could be seen in front of the Student Union. They were holding up large signs with Bible verses and futilely preaching to offended, derisive students. The preaching was nothing new: sinners, according to the main preacher on the makeshift stool-podium, were hell-bound for lying, stealing, committing adultery – the works.

Jim Hamilton, whose business card gave him the title of “The Street Preacher,” was happy to explain why they were preaching continuously anger-provoking beliefs.

“He’s answering questions that were being asked to him, you know?” he said, referring to the preacher on the podium. “The students pretty much themselves raise the agenda. And, of course, what’s at the front of their mind is what comes out, you know? So we get a lot about atheism, we get a lot about evolution, and we get a lot of – well, the hot potato, of course, is homosexuality. Everybody’s obsessed with that.”

He showed his Bible, where he bookmarked and highlighted 1 Corinthians 6:9. The verse claims that homosexuals, among thieves, drunkards, and swindlers, are prohibited to inherit the kingdom of God.

“But why this obsession, I ask you, with that subject?” he said.

Indeed, the obsession and simultaneous suppression of the subject can be seen as a phenomenon in the United States, even in progressive states like Massachusetts.

Julio Capó, Jr., an assistant professor in the department of history who teaches a lecture on LGBT and queer history of the United States, believes the obsession is deeply and historically ingrained in our culture. LGBTQ-inclusive sex education, he said, remains largely misunderstood, misrepresented, and underfunded, and the circumstances are nothing new.

“So many discussions strictly limited conversations of queer and same-sex relationships to anxieties over disease, contagion, and infection,” he said. “Queer and transgender bodies were perceived as undesirable or as case studies for medical fields, which has left a legacy of silence, erasure, and stigma that has been hard to overcome. How can you provide sex education to communities whose sexual experiences have historically been understood as abnormal, immoral, or unnatural?”

Capó mentioned that transgender individuals, especially trans women of color, are disproportionately at higher risk for HIV infection. He believes it is important to combat stigma and eradicate harmful conditions certain communities constantly face that produce higher-risk environments, such as violence, oppression, discrimination, and poverty. He believes in engaging in conversations that allow people to stay mentally and physically healthy and maintaining a sex positive image without shaming their sexual practices or bodies. And, all the while, we must remain actively engaged with discussions across racial, ethnic, gender, age and class lines.

Many queer undergraduates also agree that progress for a more inclusive upbringing is due. Nick Ozorowski, a sophomore political science major, said sex education in high school is completely flawed because many states still focus on abstinence and pregnancy rather than sexually transmitted disease and infection prevention. He called the system “completely exclusive” of queer and trans people and what it means to practice safe sex and maintain a healthy sexual identity as a queer person.

STDs and STIs, Ozorowski said, are something that currently and historically plagues the queer community. He believes most queer people are good at self-education, which reflects the LGBTQ community’s resilience and resistance to systemic oppression. But there could be a better alternative, he believes, to the current ultimatum of either remaining completely uneducated or doing all the work oneself.

Ozorowski, who kept his sexual identity hidden in high school, came out immediately after coming to college. He did not have any queer friends at the time and found no real safe sex education, even as a college student.

“It’s still very heteronormative in many senses,” he said, referring to sex education. “I think a lot of peer education systems are still very heteronormatively focused.”

This is the case even at UMass, he said, though Stonewall is a great resource. He said he found answers to his questions via the Internet and word of mouth. He added that the queer community is very inherently supportive of one another, which creates a dynamic of combined personal research with inter-culture communication.

While he never had any personal experience with STDs or STIs, Ozorowski said proper sex education breaks the stigma and the personal shame around being tested, being aware of oneself as a sexual body, and having a sexual identity. Because queer sex education is barely existent, it creates stigma around being tested and aware.

“I know a lot of people that don’t get tested, mostly because they think, ‘Oh, I can’t have an STD.’ But you can. They’re very prevalent. And they’re very prevalent because the queer community is just smaller,” he said. “There’s just not as many of us. So I think definitely an improvement in queer education would lead to a deconstruction of stigmatized testing.”

In terms of on-campus resources for queer sex education, Ozorowski recommended the Not Ready for Bedtime Players, an award-winning peer sexuality education comedy troupe formed at UMass in 1988 that performs free for students every Wednesday night during the fall and spring semesters in residence halls. Audience size ranges from 25 to 100 students per show. He called them “super inclusive” because they establish diversity.

Lily Cigale, an NRBP troupe member, said the group calls itself a sex-positive, comprehensive, sexual health education comedy troupe. “Sex-positive” means being positive about all aspects of sexuality, void of shaming or preaching the “right” or “wrong” way to have sex. “Comprehensive sexual health” alludes to thinking about sex for all demographics, not just straight or cisgender people.

But, Ozorowski said a comedy troupe should not be the only mainstream source of sex education at the university.

“I think UMass can do better,” he said. “Oh, but I don’t want to sound too shady to UMass, because UMass is great.”

The NRBP is easily one of the most explicit organizational resources for queer sex education, or sex education for all demographics. A Tommy Thompson, a prevention specialist at the Center for Health Promotion who works with the NRBP, said the troupe performs skits about safer sex, relationships, bias and bigotry, breaking down stereotypes and more. The troupe has one skit, for example, based off a real-life experience that focuses on a lesbian couple being sexually harassed by a straight man at a party.

“So, in terms of how much we’re focusing on queer health?” Thompson said. “I would say a fair amount. We’re talking about identity a lot. We’re talking about how not just sexuality and our preferences or whatever are parts of our identity but also race, class, gender identity – we’re trying to bring in the full picture.”

Troupe members go through their own growth, too. Thompson said there are a fair amount of cisgender straight men in the troupe that come to “do their own work” and unpack their own internalized homophobia.

Theatre is a great medium, Thompson said, not only because it is disarming, but because audience members questioning their own sexuality (a prevalent collegiate occurrence) can “chew on” the skit content without having the spotlight on them, as opposed to in a workshop or close-knit discussion group. Being able to identify with characters, both in NRBP skits and general media today, provides the dynamic of a simultaneously safe, detached anonymity and model for self-development.

To that, Thompson added, “Thank god for Glee.”

Thompson attributes a vast majority of their knowledge of sexual health to working at Girls, Inc., a national organization that aims to sponsor leadership in school-age girls, in Holyoke as a trained sexual health educator. The sexual education certification series Thompson went through in order to educate others is what actually provided their own education.

Along with working in the Center for Health Promotion’s BASICS program and the Collegiate Recovery Community, Thompson has worked in sexual health education for the last seven years, in Holyoke and at UMass. They believe the current system is flawed and said, “I see it as a social justice issue: providing accurate, factual, non-judgmental information to people about their bodies, about their choices, about how to create and have informed choices that would affect their body. I see that as very much an access issue. So, of course it’s going to disproportionately affect the LGBTQ population.”

In terms of where to get information, Thompson recommends Stonewall and UHS, as well as attending a NRBP show. Reiterating Becker, they said it is a great resource for people to get tested and talk to a provider. Most students are on the Student Health Benefit Plan, so it will not cost money. The counseling, however, is too abbreviated for what some students may need. If students are seeking more intensive counseling, Thompson highly encourages Tapestry Health, , though it would cost money.

Thompson agrees there is no “straight answer” on the Internet, as opposed to the straight answers given to heterosexual teenagers in the classroom.

Things are not as straightforward as they seem. A condom is a good example, Thompson said.

“So a condom is protecting for some things — for some skin-to-skin contact and some fluid transfer — but there’s a whole area down here that’s getting touched.”

Among the many crises resulting from queer stigma and lack of proper resources, Thompson also cited that queer, bisexual and lesbian high school-age young women have disproportionately higher pregnancy rates. In fact, they are twice as at risk of unintended pregnancy than their heterosexual peers.

“This is just an example: one of the groups I worked with in Holyoke, a 17-year-old girl was out, proud, like, ‘I’m a dyke, I love girls, I’m into this.’. And she was in my group and the curriculum I was using was comprehensive and inclusive. But, also, one of the sections was a condom demonstration. And she was like, ‘I don’t need to pay attention to that. I don’t need to use those.’ And I was like, ‘I totally get it, you know, but if you’re going to be using sex toys you’re going to want to be safe about it. There’s still fluid involved and you’re going to want to know what’s going on.’ And she’s like, ‘Alright.’ She stuck around for that. She stayed in my group. And a couple months go by and she comes in and she’s pregnant.”

Thompson stressed that orientation and behavior are different, and that unprecedented circumstances can occur despite expectations of your own behavior. It is not about how you identify in terms of your sexual orientation, but your behavior that matters in terms of safe sex and relationships. The girl from Holyoke, for example, identified as gay but still had heterosexual sex.

Thompson grew up in Toussaint, Arizona where they had very little sexual education, even through a normalized, heterosexual lens. A lot of exposure happened after high school, when they attended Smith College as an undergraduate. Neighboring students in the dorm, they said, were the ones to unveil previously foreign and surprising concepts, like barrier methods.

Thompson called their own experience as a young queer person “isolated and brutal,” agreeing that societal structure contributed to their negative experience. They attribute a lot of their problems growing up to internalized homophobia and not wanting to be queer.

Thompson went to friends for sexual health information for many years, which they now look back on as inadequate and inaccurate. A lot of their “growing up” and education came from learning to be an educator themselves. “Resources? Yeah, they were there. Did I access them? No. I didn’t know how to do that.”

Thompson stressed the importance of the NRBP as a peer education model. “We could put a million resources out there, but if people don’t know how to access them, they’re going to be accessing information through their peers.” It is crucial that as many undergraduates as possible have accurate information and are as inclusive as they can be in terms of their thinking, “whatever that looks like.”

Regarding the near and distant future of inclusive sex education, Thompson hesitated, sighed and said, “I’m going to sound really cynical.”

While inclusive sex education is progressing and Massachusetts is leading the nation in respect to this inclusivity, there is a false perception of acceptance where young, queer people are still struggling and sometimes committing suicide due to lack of support from family and their community.

Thompson urged students on campus to be vocal, let their staff, administrators, professors, residence directors and residential assistants know if they want more information.

“The university will respond to that,” Thompson said. “There are these resources that are available. And could we be doing more? Definitely. Without a doubt.”

Cigale also believes that, while education is moving in the right direction, the current system is wanting.

A public health and social thought and political economy double major with a minor in women gender sexuality studies, Cigale focuses on community health education for groups of marginalized people because there are so many health disparities. She connects sexual health with mental and emotional health. If a version of a sex life is not represented or educated on, people who practice that sex life will not know how to protect themselves or make that sex life emotionally healthy.

“It’s so easy in our weirdly sex-negative society to feel really bad about your sexual preferences and your sex life and the things that you do,” she said. “There are people all over this country, definitely all over this world, whose health isn’t being prioritized.”

Cigale mentioned the importance of health equity, which is different from health equality.

Equality, she said, is infeasible in the case of comprehensive sexual health because it would require the marginalized group to have the same opportunities as the dominant group. Right now, the differences of the marginalized group (queer people, in this case) hinder the group from getting the resources it needs, like access to health education, barrier methods, and abortion clinics.

Cigale believes equity is about even access to resources, as opposed to equality, which sounds great in theory, but does not take into account the different complexities of people’s identities that lead to their oppression.

“And the dangerous thing about privilege is that you don’t necessarily notice it,” she said. We’re talking about heterosexual sex ed, but it’s not framed as heterosexual sex ed. It’s framed as sex ed.”

Cigale had heterosexual sex education in a New York public school, which she said sufficed. As someone who identifies as bisexual/pansexual and is currently in a heterosexual relationship, the education applied to her. But, like Ozorowski, she did not confront her queer identity until she came to college. She said her heteronormative education was ingrained in her, which blocked her from understanding herself and her sexual orientation.

Cigale did not go to Stonewall for information, but found it primarily through NRBP. She saw them for the first time at Summer New Student Orientation and auditioned first semester of freshman year. She believes joining the troupe helped her with the transition.

Her learning process for understanding sexual health, like Thompson’s, came from learning to educate other people. In order to be a successful health educator in the troupe, she had to learn the material. She advocates doing academic work surrounding one’s identity, as she is studying queer health education and health education for women.

“That has been very empowering for me. That has been really healing, almost. Because it’s almost easier to look outside of yourself and think, like ‘Oh, of course queer people need to be educated and be able to feel good about themselves and their sex lives.’ And then you’re like, ‘Oh, I’m queer people. I need to be educated and feel good about myself and my sex life.’”

She said that having a sexual identity not shown by society evokes a feeling of powerlessness.

“You’re sitting in sex ed class and what they’re talking about isn’t what you want to do and isn’t how you live your life. You can feel so erased, so invisible. And then, when you are able to kind of take charge of this and do this work, it reaffirms the fact that you’re alive, you’re a person and the stuff you’re doing matters. And then, when you’re talking about change: I feel like I am doing the change.”

Change is not just happening for Cigale. She, along with countless others worldwide, is the one implementing it. Because of this, she said, the process of understanding her identity has not been a crisis the way it is for many queer people emerging from the closet. She does not think about change passively, but rather as something she, her colleagues, friends, and people like Thompson are implementing.

“And not just queer people,” Cigale said, “but underrepresented minorities who are actively doing that work and forcing society to make a place for them.”

Cigale said the fight for a more inclusive environment for LGBTQ youth is just one of the many arduous progressive journeys for the minority groups of this country. And, as for the queer community, which has seen huge changes this past year, there is trudging hope for the future. The change, as Cigale said, starts with those who want it.

Sarah Gamard can be reached at [email protected].

Jessie • Oct 9, 2015 at 6:23 pm

What a wonderful article! I congratulate all these brave students who are insisting on basic human rights for all. The world is a better place when we can be who we really are.

Excalibur • Oct 6, 2015 at 12:52 pm

LGBTQ tries to silence and punish all who disagree with them. They are the new Thought Police. They are the new Stasi.