Associate Professor Eric Poehler of the University of Massachusetts classics department recently received a grant worth $245,000 from the Getty Foundation for the three-year long Pompeii Artistic Landscape Project.

The project is meant to digitize and contextualize the ancient art of the Roman city of Pompeii in an online database and open source tool for all to use.

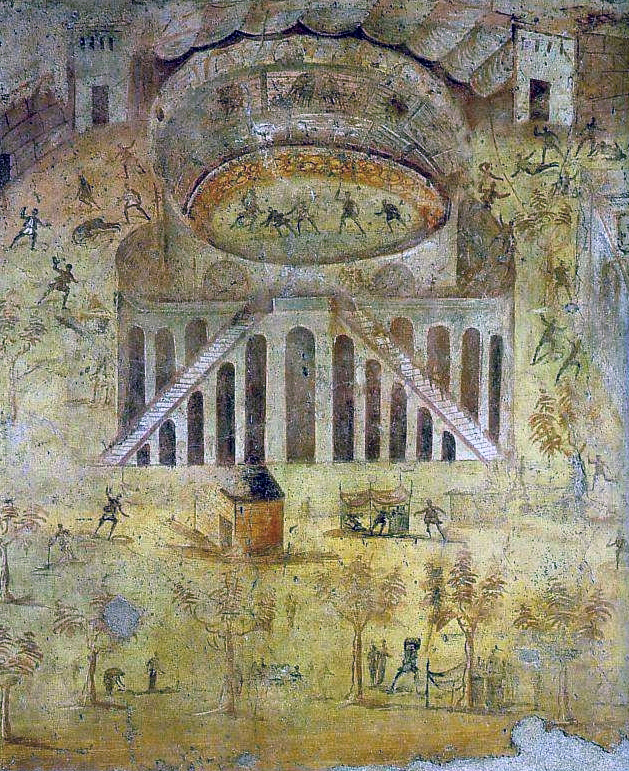

In A.D. 79, Pompeii suffered a catastrophe that buried the city under pyroclastic flows of heat, gas and ash that erupted from the neighboring volcano, Mount Vesuvius, according to Encyclopedia Britannica. The destruction ultimately preserved the ancient Roman city’s buildings and artwork for centuries, making it a treasure trove for modern day archaeologists.

Poehler said he became enamored with Pompeii over 20 years ago when he first visited as a student and has since become a specialist. His previous work on the digital and interactive Pompeii Bibliography and Mapping Project was a predecessor to his work on the PALP.

In a description of its mission the PBMP’s website states, “The Pompeii Bibliography and Mapping Project intends to explore the ways in which the former kind of landscape, the physical, can be employed to structure and examine the latter, metaphorical variety.”

According to Poehler in a phone interview, the PALP grows out of the work of the PBMP to look at and draw connections from specifically the artworks found in and adorning the ancient city’s 640,000 square meters, 1,100 buildings, 15,000 individual rooms and about 45,000 walls.

The work of examining this artwork has previously been inaccessible and infeasible to most, Poehler said, as it has been confined to mostly obscure, expensive and relatively rare Italian catalogs and publications. He added that painstaking work was often required to contextualize this artwork.

In a nod and reverence to the work of his predecessors in compiling this information, Poehler said, “Their work was just incredible, and we’re deeply reliant on their work to do what we want to do,” but he added, “We do want to unlock that and [the PALP] is one of the ways we’ll be able to do that.”

In an explanation of how the system will work, Poehler gave the example of examining a painting of the mythological figure Hercules, noted for his signature club in hand in depictions.

Poehler said in using PALP, one can only identify the act of holding, but also the image as a whole and how it compares to other images in the same room and then to all of the paintings in Pompeii through the interrelated database of all the artworks.

“That makes interesting and unique searching and research possible,” said Poehler.“Not only would you be able to then find these instances, but you’d also have a map that shows you exactly what walls and what rooms and what buildings and what neighborhoods [the artwork] existed in, and you’d also be able to quickly pull up those images and make comparisons.”

Poehler added that each digital object will have its own unique resource identifier and address in order to label and describe the hundreds of thousands of individual objects in the online map. Amateur scholars and experts alike can then link to these items in order to share their speculative research leads using a shared infrastructure of facts, vocabulary and references at their disposal.

“So whenever anyone from now on ever wants to talk about a particular wall or a particular room, they won’t [have] to worry about [whether] it has this name or that name, they can just point to it because we will have published essentially a new digital version of what the world of Pompeii looks like,” said Poehler.

The three-year-long project won’t be complete until fall semester of 2021, according to Poehler, but in those three years, Poehler will work alongside a host of partners and collaborators.

A press release by UMass News & Media Relations identified the PALP as a collaborative effort between Poehler and Sebastian Heath of New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World.

Poehler described Heath as a “foremost expert” on using digital innovation in the world of archeological data, the pair having met a number of years ago.

Poehler added that the kernel of the PALP came from early talks with Heath which then led to initial informal conversations with the Getty Foundation almost one year ago.

Other collaborators include the group “Pompeii in Pictures,” who had previously worked with Poehler on the PBMP and who provided the pictorial tour element of the map, allowing users to see into the streets and rooms of Pompeii as if they were there firsthand. Their work will continue in the PALP to collect and describe as many images as possible of the city’s artwork.

Additionally, Poehler is employing a team of currently seven undergraduate students ranging from freshmen to upperclassmen, who are not only classics and art history majors, but also some computer science majors.

Junior classics major Stefanie Taylor is one of those students and a leader among the undergraduates. Taylor, who has been a student of Poehler’s in the past taking a class specifically about Pompeii with him last semester, says she became interested in classics through an early love for Greek mythology.

“I like that this project lets us see kind of the human interaction with the landscape itself, like paintings on the walls and like how we express ourselves then and now,” said Taylor.

Taylor was keen on the prospects of the project now that it has received grant funding as well.

She said, “I’ve done a field school before so this is a nice other side of being able to experience archaeology and not just being out in the field, but like the analyzing of facts that can help people in the future.”

“What excites me is that this work is going to be able to help archaeologists and people who are just interested in Pompeii going forward,” Taylor added.

Poehler says that the $245,000, which he described as a “quite large grant” in the humanities, will go directly to human capital and the benefit of students, which Poehler says he is proud of.

“One of the reasons I mentioned we’re hiring people even in their first year, people who are just keen and excited and hard workers, [is] because working with them most of their college career if possible would be a really great opportunity to provide someone,” Poehler said.

He added, “I’m real proud to be able to bring that to UMass.”

“[What] I think is important about a project like this [is] it helps to make it clearer, that we here in the classics department, who work on an ancient world that is long gone, work on languages that are rarely spoken around the world anymore, ancient Greek and Latin,” Poehler said. “It’s easy to assume that because work on topics that seem esoteric and very different from the modern world [that it’s] also hard to figure out how they attach to say getting a job.”

Poehler continued, “[But] it’s important for me to point out that we work in the modern world, even though our topic is in the ancient world, and you can develop intellectual and technical skills in a classics department that can lead to employment.”

Chris McLaughlin can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @ChrisMcLJournal.