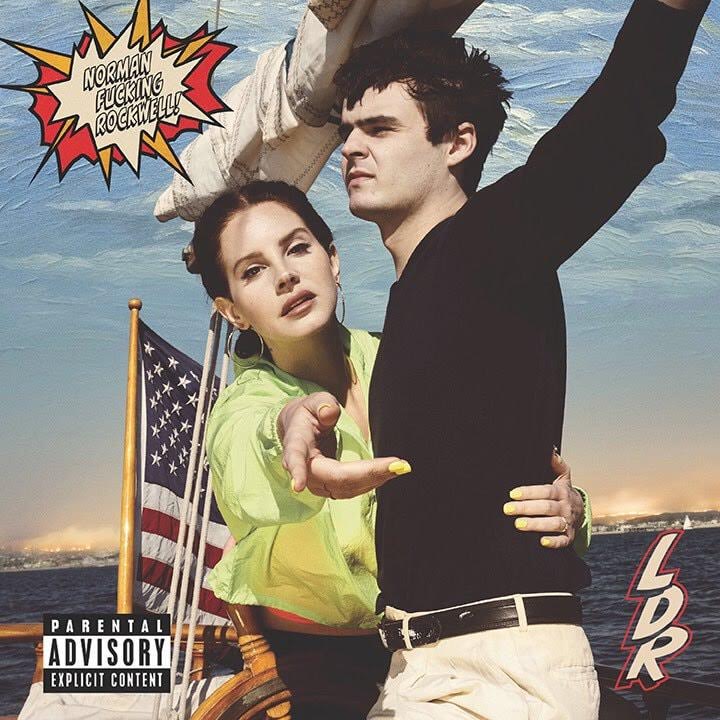

Lana Del Rey appears to take on a new persona with each album she releases, from the glamourous all-American starlet of “Born to Die” to the dark seductress mourning life and love on “Ultraviolence”. With the release of her sixth studio album, “Norman F—ing Rockwell!” Del Rey strips down to her most compelling character yet: herself.

In the opening line of the album, Del Rey croons, “Goddamn, man-child/ You f—ed me so good that I almost said ‘I love you,’” is not shocking in its vulgarity, but in its unembellished and matter-of-fact tone. The whole of the titular first track sounds lyrically like an unedited diary entry, a refreshing departure from Del Rey’s lyrical hallmarks – shining descriptions of Hollywood life and cinematic but somewhat impersonal recounts of failed love affairs. The Del Rey of “Norman F—ing Rockwell!” is more assured and mature than she’s ever been. She asserts that she “Ain’t no candle in the wind” but quickly follows it up by calling herself a “Venice bitch,” as if to prove that it isn’t how she labels herself that really matters, but the fact that she’s the one holding the pen.

Sonically, the album offers few surprises for those who have listened to Del Rey before. Her 1970s-esque sound, defined by lengthy outros, hazy distortion and a whispered layering of vocals is more polished than ever on “Norman F—ing Rockwell!”. The melodies are not only meant to be catchy, though Del Rey’s knack for crafting infectious hooks is undeniable, but they add to the narrative of each song. “Cinnamon Girl” is perhaps the most salient example of melody informing the narrative. The verses where Del Rey laments, “all the pills…violet, blue, green, red”, that her partner takes are simple and bouncy, reminiscent of a nursery rhyme; while the chorus becomes grander and Del Rey seems desperate as she sings, “If you hold me without hurting me you’ll be the first whoever did”. The surface level excitement and danger of the relationship are addictive but uncomplicated, outshined by Del Rey’s personal fears stemming from her past, as represented by the shift in melody from catchy to grandiose.

The narrative arc not just of individual songs, but of the record as a whole, is what makes “Norman F—ing Rockwell!” feel more complete than any of Del Rey’s previous albums. In “Love song”, the golden age of a relationship is closely connected to the car Del Rey’s lover drives, conjuring nostalgic images of high school sweethearts. The car then becomes a place of conflict in the penultimate song, “Happiness is a butterfly”. Del Rey’s light, steady vocals throughout “Love song” that convey the peaceful beginning stages of a relationship make her uneven shouting, “‘Don’t be a jerk, don’t call me a taxi’/sitting in your sweatshirt crying in the backseat,” that much more gut-wrenching, as the listener has a stake in the relationship that’s now falling apart.

At fourteen tracks, the album has few superfluous songs. Each new track builds on the last, or at the very least, reveals a different facet of the relationship expressed throughout the album. That being said, the two weakest songs on the album are “How to disappear” and “The greatest”. The latter is a five-minute ballad lamenting the current state of the world where “Kanye West is blonde and gone” and “‘Life on Mars’ ain’t just a song.” While not exceptionally profound, the cultural critique presented would be more intriguing if it wasn’t messily tagged onto the end of what, until the last verse, is a track about Del Rey missing bars and friends in Long Beach. “How to disappear”, on the other hand, is lyrically solid and not necessarily a bad song. However, it borders on simple, never really expanding past the basic premise of Del Rey falling for men who don’t reciprocate her feelings. Put simply, it lacks the panache of Del Rey’s best songs and, as a result, leaves the listener unsatisfied.

The remaining 12 songs are unquestionably the most sonically and lyrically consistent body of work Del Rey has put out to date. “Norman F—ing Rockwell!” feels like a first glance into the psyche of the notoriously private Del Rey who, up until now, has always seemed like more of a character than a real-life woman. On the last track, Del Rey recounts the “Church basement romances” and “high heels on white yachts” of her past but comes to the quiet conclusion that those things no longer represent her. While her lyrics may still play off of old Hollywood tropes and Californian imagery, the meaning behind Del Rey’s words has never been as honest or as skillfully executed as it is on “Norman F—ing Rockwell!”.

Molly Hamilton can be reached [email protected].