The W. E. B. Du Bois Center at the University of Massachusetts hosted a virtual panel discussion on Thursday, Jan. 21 discussing the role of government surveillance and policing in the lives of W. E. B. Du Bois, Shirley Graham Du Bois and other Black radicals primarily during the 20th century.

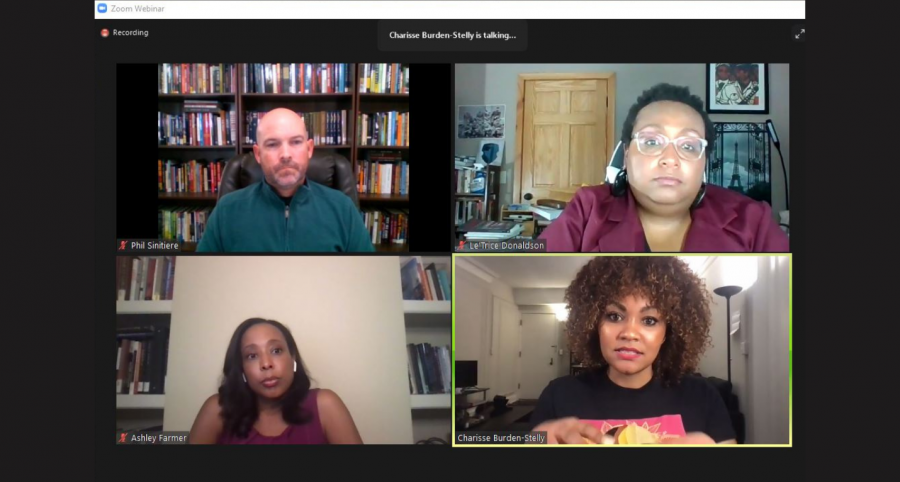

The two-hour-long event, “Resisting Repression: W. E. B. Du Bois, Shirley Graham Du Bois, and the Surveillance State,” featured scholars from different universities across the country.

Ashley D. Farmer, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the Departments of History and African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Charisse Burden-Stelly, Ph.D., is the 2020-2021 Visiting Scholar in the Race and Capitalism Project at the University of Chicago and an assistant professor of Africana Studies and Political Science at Carleton College. She is also a former post-doctoral fellow at the Du Bois Center. Le’Trice Donaldson, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of African American and U.S. history at the University of Wisconsin-Stout.

The webinar was moderated by Phillip Luke Sinitiere, a Scholar in Residence at the University’s W. E. B. Du Bois Center, while the question-and-answer portion was led by Adam Holmes, the program manager at the Center. According to Holmes, over 120 people attended the virtual event.

The discussion was split into three sessions structured around several discussion questions for the panelists to respond to.

Sinitiere began by considering the significance of holding this event in 2021. “I want to note that having this discussion in 2021 marks the 70th anniversary of Du Bois’ indictment as an alleged foreign agent in February of 1951,” he said. Sinitiere added that in that same year, Du Bois was acquitted of the charges, representing a critical moment of resistance to anti-Black repression amidst the Cold War.

In the first session, Sinitiere posed the following question for the panelists to consider: “What are some of the historical factors, both nationally and internationally, that shape the surveillance of Blackness in the early 1900s, especially as it relates to Du Bois and the era of World War 1?”

Donaldson began the conversation by highlighting the influence of military intelligence programs on the FBI’s methods of surveillance. Under the Military Intelligence Division, a surveillance program entitled ‘Negro Subversion’ was created. This program would later help shape the FBI’s COINTELPRO program, she said. According to the FBI website, Counter Intelligence Program was created “to disrupt the activities of the Communist Party of the United States.”

“[The FBI] took their playbook from the military,” Donaldson said. “The military decided in 1920 that they would supposedly stop monitoring African Americans or ‘Negro Subversions,’ but they didn’t. That file didn’t close until 1941.”

Farmer spoke on a similar note of federal surveillance initiatives, bringing up the Radical Division Surveillance Program that developed through the Justice Department.

“I think there was no coincidence that this develops at the same time that we have the Red Summer of 1919, which if you don’t know was a wave of white supremacist violence against Black people, many of those who had come home from the war,” she said. Rather than focusing on white supremacists, the government shifts “the focus on subversive elements instead.”

At the end of World War I, the Communist Party was “organizing Black folk with unparalleled fervor,” Farmer explained. The group’s success laid in advocating for “Black nationhood,” “Black self-determination” and “Black working-class fights.”

Although the hysteria didn’t become widespread until later on in the 20th century, Farmer said that the idea of a communist being anti-American and also “a friend of Black people or the Negro helps further intertwine this idea of anti-Blackness into subversiveness into something that the government wants to surveil.”

Burden-Stelly drew similar parallels between anti-Blackness, communism and government surveillance. She offered the Dies Committee as an example, which was created to surveil and gather information on fascism and communism.

“It’s just very quickly only focusing on communism,” Burden-Stelly said. “And this is . . . imbued, or sort of rooted in anti-Blackness. So for example, one of those questions that they ask people to see whether or not they’re communists is if they’ve had Negroes in their home, or how many Negroes are [there] in their organization.”

Session two of the discussion revolved around the following questions: what historical conditions in the “40s and 50s shaped such vicious and pernicious harassment of W. E. B. and Shirley [Du Bois],” and “what did the U.S. government find so threatening about Black leftists?”

Burden-Stelly began the conversation by pointing out how civil rights and economic redistribution were labeled as “communist adjacent,” which became “a way to . . . discredit or to undermine those efforts.” The United States was able to maintain the racial hierarchy in a way that also gave “nominal rights and some privileges to particular classes of Black and racialized people,” she said. “And anti-communism becomes a very effective way to do this.”

By discrediting and criminalizing the radicals involved in the movement, “only the more liberal or moderate elements are . . . left,” Burden-Stelly said.

Another way that Black radicals were hindered in their work was through “financial terrorism.” The monetary price of being under surveillance by the U.S. government, facing arrest and going to court is “very, very expensive,” she said.

Further, those that were subject to surveillance by the state also found themselves unable to find employment, venues or publications for their work. “. . . If you’re even adjacent to or you don’t critique these Black radicals, you could get [surveilled] too,” Burden-Stelly said, explaining the fear of association that many had towards radicals.

During this time period, Black folks in America were experiencing a dual fight: “a fight against fascism, abroad, [and] a fight against racism at home,” Farmer said. She responded to the session’s prompt questions by examining the role of Black women during the World War II era.

Black women stepped up for the fight at home in various ways. Sojourners for Truth and Justice, a group of which Shirley Graham Du Bois had membership, was a “Black left feminist organization . . . that has some nationalism, some communism and some feminism all rolled into one,” Farmer said. Due to the nature of government surveillance, “almost every single woman that was in this journey for truth or justice . . . has an FBI file.”

Donaldson remarked on the government surveillance as well, or rather the “ineptitude in American surveillance.”

“They’re so focused on communism, . . . the amount of money and resources dedicated to investigating communism allowed for homegrown domestic terrorism to flourish and grow,” she said. “They’re looking at Black identity, you know, Black Lives Matter, they’re looking at the Black Panthers, and they’re looking at Claudia Jones, and they’re looking at an elderly Du Bois and his wife instead of looking at the Klan and looking at how these people are being elected to state officials, imposing these domestic programs that would make the United States horrible.”

For session three of the panel discussion, Sinitiere prompted the scholars to consider these final questions: “Based on Shirley and W. E. B.’s individual and shared experiences of the surveillance state and anti-Black, anti-communist state repression, what buoyed their spirits? What tactics and measures did they, and other Black radicals, take in resisting repression?”

Farmer led the responses by re-highlighting the surveillance done on members of the Sojourners for Truth and Justice. To push back against this, they would “basically tell the state ‘we know you’re watching us,’” she said. The women would write to FBI agents to make known that they knew they were being surveilled, Farmer explained, and to demand that they stop. Members of the Sojourners also wrote articles about their experiences with the FBI.

“I think this was important not only for them to kind of bear testimony to their own treatment,” Farmer remarked, “but also to let those in the community know what was happening, [and] what was happening when they saw agents surveilling them.”

By engaging in various direct methods to hold those surveilling accountable, the women developed an official record “to make sure that we have a document of them resisting this kind of surveillance and building community inside of that,” Farmer explained. She warned, however, that the FBI records should be read with suspicion “or through the lens of FBI agents.”

Donaldson said she would like to “piggyback” off of Farmer’s points but in a different direction. She drew attention to the trust dynamics between the radicals facing surveillance. In the cases of Du Bois and Martin Luther King Jr., for instance, it was evident that people in their lives were willing to inform and give up information on them, Donaldson said.

“You couldn’t trust your friends, right?” She said. “You didn’t know who was an informant.”

While Burden-Stelly agreed, she pointed out the continued “comradeship” between Black radicals. Despite the surveillance upon them and the fear during the Cold War, Black radicals were able to accomplish a lot, she said.

“I think it’s profound that even with all that snitching, . . . even with all of that distrust, these people still love each other, they still had each other’s backs, they still wrote for each other, they still help each other, they employed each other,” Burden-Stelly remarked.

The webinar concluded with a question-and-answer session with the audience.

Approximately halfway through the event, the speakers paused their discussion to address a Zoom-bombing incident in the panelists’ chat. The matter was handled swiftly, and the individuals were removed by the event organizers.

The W. E. B. Du Bois Center has an upcoming webinar, titled “Children of the Sun: Celebrating the 100-Year Anniversary of The Brownies’ Book,‘” on Feb 23, Du Bois’ birthday.

To access a recording of the webinar, contact Adam Holmes by email at [email protected], or message the W. E. B. Du Bois Center on Twitter at @DuBoisUMass.

Sara Abdelouahed can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at @AbdelouahedSara.