Syria has been subject to a decade of civil war. Dania Halak hopes for the day her home is rebuilt.

Collecting berries with her grandfather on his mountainside garden, exploring castles carrying centuries of history with her parents and running around with her cousins as the scent of the food they would later be sharing filled the room — Halak’s childhood in Syria was a constellation of fond moments with her loved ones.

“Growing up in Syria is like a dream,” Halak said.

Now, sitting in her freshman dorm room in Amherst College, Halak poignantly reminisces on the years behind her, spent in Syria, Lebanon and the United States — overwhelmed with love for her country and an aching desire to return home.

“All my friends, they have immigrant parents, but they were born here,” Halak said. “In this case, I am the immigrant. So, the same way that my friends talk about how their parents miss their home… I miss my country, and I love my country.”

10 years have passed since Halak’s home country of Syria began to spiral into destruction. Nearly a decade since Aleppo, the city that she considered to have “always been safe” and a hub of history and culture, would begin to be scattered with ruins.

Halak was born in Damascus but later moved to Aleppo, where she spent the majority of her childhood until the Syrian Civil War forced them to flee. The war, which began as a peaceful uprising against the Assad regime in 2011, has now killed over an estimated

500,000 people and displaced half of the country’s population.

It pains Halak to see the location of her fondest childhood memories be destroyed. A place so abundant with irreplaceable history — belonging to both Syrians and the other groups who have found refuge in the country

“It makes me really sad. Not only because I’m Syrian, but because those people who fled to Syria and tried to preserve their own history. Now their history is also being erased,” Halak said.

But her early memories of Aleppo are rarely filled with war. She recalls the city brimming with excitement, boisterous people and lively settings.

“Aleppo is like alive 24/7, it never sleeps. There is always something happening. There’s always noise,” Halak said. “People who live in Aleppo love to have fun, they love to like host gatherings and parties and like my family would like to go to parties all the time.”

Although her understanding was clouded with childhood naivete at the time, she now sees the subtle changes in her surroundings that signified a larger shift in the country.

She could no longer walk through the streets of Aleppo at night with her brother to buy soda in glass bottles. The price of cherries, a staple of Syrian cuisine, was becoming too expensive for her household to afford.

Her trip to school was also becoming more complicated.

“People started getting really scared of going to school,” Halak said. “Before we even left the school, the bus would have to wait five minutes. And we didn’t know why. But I think it was like maybe they were making sure that the road back was safe.”

These minor changes culminated into the moment that Halak’s family realized that they had to depart. The University of Aleppo, the second largest university in the country which stood right across Halak’s home, was bombed in 2013

Education was an integral part of Halak’s life. She describes vivid memories of her grandfather picking her up from school to bring her back home, where her family would be waiting to hear about her day.

Education is also an integral part of Syrian society. When the university was destroyed, so was what it symbolized.

“Clearly our identity and who we are as Syrians is like, no longer something… that is valued,”Halak said, describing the bombing. “The Syria that we know is no longer there. Because the identity of being Syria is like being destroyed in front of our eyes.”

Although war had already been waging in surrounding cities in Syria, she had not thought it would reach Aleppo.

“I think nobody believed that anything would happen in Aleppo,” Halak said. “Because like the history there, like there, there’s so much at stake to be hurt and to like, if you like if anything happens to Aleppo, which is the trading center of Syria, then like the whole thing falls apart.”

The bombing killed dozens. Halak and her family had been going back and forth between Lebanon and Syria for some time, but they then knew they had to leave their home behind.

“We did not want to leave Syria. I think that was like a shared feeling between everybody who was there,” Halak said.

Halak grieved her depart from her home, and the hostile welcome that she received when they first arrived in Lebanon added salt to the wound.

She recalls an incident where one of her teachers, unaware of Halak’s heritage, spewed hateful remarks against Syrians.

Halak describes the words of her teacher at the time, who was saying that the same way someone would step on a cigarette, is the same way that they should “step on those Syrian” in order to stop them from “coming to this country and ruining the country.”

In another incident, Halak had the highest-grade average in her class, but was placed second due to her Syrian nationality.

Halak initially expressed her Syrian heritage with great pride, she later went great measures to avoid prejudice from her classmates and teachers. She switched schools and adjusted her authentic Syrian accent to mask her heritage and melt into Lebanese society.

“I think the only thing that was Syrian about me was the license plate of my mom’s car,” Halak said.

When Halak and her family arrived in the United States, they eventually settled in Revere, Massachusetts, where she attended high school. One of the things that stunned her following her arrival, was how unequal education was and her difficulty in receiving guidance throughout the college application process.

“I wouldn’t say misled because I don’t think I was led at all,” Halak said, describing her high school experience. “It didn’t really make sense to me how they [other students] knew a lot and they had the resources and I didn’t, because we went to the exact same school.”

“I don’t think this world was kind to us,” Halak said. “Syrians have just a sweetheart, they’re really kind. And because they’re so generous, and sweet and kind, people step over them.”

Halak now proudly carries her Syrian identity in Amherst, fervently telling her friends about the rich history and sublime culture of Syria — home to poets, scholars and pioneers in medicine and education. Above all, Halak wants the world to know of the kind hearts of Syrians and their love for knowledge, history and literature.

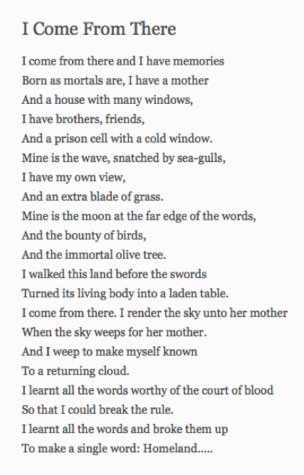

“There are so many… Syrian poets and authors,” Halak said. “Even if you didn’t go to school, you would hear about them because the arts, whether that is like poetry, writing or even like traditional dances or music, is such a staple of the Arab identity and specifically like the Syrian identity.”

She especially has a fondness for the beautiful prose and complex language of Arabic poetry. She cited Mahmoud Darwoush, a Palestinian poet who captures the collective struggle of the Arab world against foreign powers and the fight to preserve their land.

She wants the world to know about how Syria and the “Arab world in general and the Middle East region have contributed to the world.”

“I think we just the way that we view them here in America is these like uncivilized people. We don’t view them as their own,” Halak said.

She also believes that her Syrian identity has made her understanding of the struggles of other marginalized groups across time and space.

“I also maybe like carry and the sense of like, sympathy and empathy and like, understanding for the need to preserve history,” Halak said. “The history of Syria is being currently destroyed right in front of… our eyes, and, oh my God, it hurts me so much.”

She is undecided on a major, but is especially passionate about social justice, international relations, environmentalism, scientific research, and helping people through those disciplines. Her identity has also imbued in her a passion for preserving history.

“The history of the countries in the Middle East, and the people come from the Middle East… their contributions are always like not told, especially in western countries,” Halak said. “So, I think maybe I carry my Syrian identity in this, like, understanding to preserve history and the importance of that.”

Although Halak has lived in many countries and cities, when you ask her about home, she thinks of family.

“When you’re with family, I think everything in the world means nothing, because you’re just there with them,” Halak said.

She thinks of the nights of Ramadan, when her family, usually scattered across the world, would be pulled together to gather over a meal in Damascus. Each person frantically searching for the family members in and around the house so that no one was left behind before they collectively said a prayer and began to eat.

“I think home could be just like the place where your family is,” Halak said. “I think about that Ramadan table gathering and I’m like, yeah, I think I think that’s what home feels like.”

No matter it’s definition, Halak believes that it is imperative for someone to have a place to call home.

“I think it’s important for people to find a place to call home so they can find stability, so they can be able to be grounded and be able to hold on to their identity, and truly who they are without being influenced,” Halak said.

Halak dreams of the day that Syria is revived and rebuilt. She aspires to return home and serve the Syrian people, who have been crushed under the weight of the world’s negligence for far too long.

“Hopefully, when I decide on a certain career, I think the thing that’s gonna be the most satisfying in my life, or like my purpose in life would be just to go back to Syria, and try to serve it and try to try to like, rebuilt it and help the Syrian people in any way possible,” Halak said.

Her children, she hopes, will also grow up in Syria as she did.

“If I have children, and hopefully Syria is rebuilt, I would definitely go back there and like, make them grow up there,” Halak said.

Although she is hopeful, Halak also acknowledges the sobering reality that many steps need to be taken before restoration can begin.

“Hopefully in the 10, Syria would get rebuilt,” Halak said. “I think it’s a really, really aspirational dream. Because for Syria to get rebuilt, we have to stop bombing. And we have to stop the war there, which has not happened.”

It may take a lot more work to seize Syria from the grips of war, but in the meantime, Halak wants Syria to be known.

“I just want Syria to be represented better. I want Syria to be advocated for. I want our history to be, you know, preserved,” Halak said.

Saliha Bayrak can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @salihabayrak_.