It was the end of the spring semester in 1970. The Beatles were still together, psychedelics were at their peak and finals season was quickly approaching. But the students at the University of Massachusetts had more important matters to attend to.

UMass students were spreading flyers around campus, calling to abolish the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps. On May 7, 1970, a crowd of about 30 students —they called themselves the Anti-ROTC Committee— were gathered inside Dickinson Hall, jamming doors with gum as ROTC cadets laid in front of doors to prevent interference.

As the United States progressed into Cambodia despite promises of war de-escalation, and a clearer picture of the gruesome reality of the war was forming, student protests rapidly spread across the nation. Students across the country were demanding an end to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, and UMass became a part of a national strike as students called for an end to the University’s complicity. One of the demands put together by the students was to abolish the ROTC on campus.

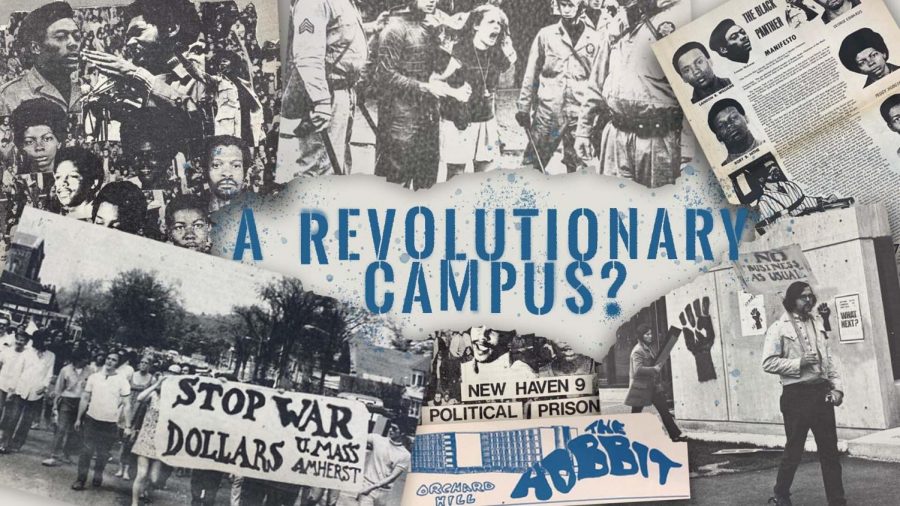

It is not coincidental that UMass and ‘revolutionary’ are often found within the same sentence. College students have long been instrumental in bringing about social change across the country, and countless social movements have found momentum at UMass. While 1970 was a significant year for protests, it was far from the end of student organization on campus.

This past year alone, hundreds of students have protested sexual assault occurring in Greek life in the wake of allegations against the Theta Chi Fraternity. Many also participated in the Be Revolutionary march, organized by the UMass chapter of the NAACP following the spread of emails sent to Black organizations containing racist language and messages.

Past and present students continue to contemplate whether the student body at UMass is truly revolutionary and unique in its ability to organize. Upon looking at UMass as a hub of social justice activism, it is worth exploring what the value of student organization is, what moves students to protest and why universities are often an epicenter of social movements.

***

During the commencement ceremony of 1970, many students sat during the national anthem as the University decided not to remove it from the ceremony despite student pleas. Peace signs and arm bands were dispersed throughout the crowd of nearly 3,000 students -and the war was still waging on.

In 1970 senior class president David Veale’s graduation speech, he said, “It is appropriate if the Southeast Asian war continues, too many of the men in the graduation class will be forced to kill or be killed.”

He continued, “We are fearful because the American political structure has no significant place for those who are young. For those who want love instead of hate, peace instead of war, freedom instead of repression, Woodstocks instead of Vietnams.”

Stephen Nissenbaum, a professor emeritus who began working at the University in the late 1960s, was active during the student strike in 1970. H

e organized a seminar to discuss the strike and pioneered an effort to create an archival collection for it.

Nissenbaum describes the time period as “inspiring.” People who were never expected to join the movement, like fraternity members, become a part of it. There was a lot of tension and anger in the air. At UMass, the news that police killed student protestors at Kent State University was announced during a concert at Curry Hicks Cage — a tipping point for many students’ attitudes towards the war, Nissenbaum explained.

“There was a lot of beautiful energy, at the same time, a lot of distaste, a lot of anger towards our parents, and towards what they represented, and what the ‘50s had been,” Nissenbaum said, describing what moved students to organize at that time.

There was anticipation that the energy on campus in the spring would continue into the fall semester and that “the University was never going to be the same,” Nissenbaum explained. Nothing essentially happened the next semester, however, and Nissenbaum remembers someone remarking to him: “I think the 60s are over.” The war would continue until 1975, and the ROTC on campus was never abolished.

“The transformation that we were expecting never happened,” Nissenbaum said. “The institution of the University proved to be a tough nut to crack.”

Although UMass has been a major point for student protesting, Nissenbaum argues that it is not necessarily unique in this characteristic. Nissenbaum attended the University of Wisconsin Madison before coming to UMass, a place he describes as another epicenter of the anti-war movement.

Kathleen McClaskey graduated from the University on May 30, 1970. She and her fellow students saw the beginning of the Vietnam War but never saw the end, she explained. Despite the seeming lack of concrete changes resulting from the student protests, she does not think that the students’ efforts to demand an end to the war were futile.

“We didn’t end the war, but we made people aware…of the travesty of this war,” McClaskey said. She also describes her generation as the “generation that woke up everybody.”

McClaskey also reflects on this period of her life as personally transformational. “This set the stage for me being an advocate for causes…it’s a great experience to protest and fight for something you believe in,” she said.

McClaskey stated that college campuses have a strong ability to organize quickly and efficiently. “Universities and colleges have the numbers to create organized protests,” she added. “Any university is a vehicle for change.”

Ryan Frisby, a 2017 graduate, shared a similar perspective as McClaskey. She mentioned that students’ willingness to protest “is not unique to UMass,” but rather to “the college experience,” particularly state colleges located in progressive areas.

After former President Trump was declared the winner of 2016’s Presidential Election, approximately 40 UMass students organized on Goodell Lawn to express their shared outrage at the election results. Frisby attended the protest.

“An undergrad space is a kind of hub for [protests], which is really nice. That was not something I experienced before I had gone to UMass,” Frisby said. Such a protest held space for students to process, make their voices heard and gather in solidarity, she explained.

When Trump was declared the newly elected president, she remembered thinking, “‘I will not be in classes today.’ That was the overall sentiment.” Referring to the protest, she said, “It was good for me to be in that space.” Frisby felt proud when she read an article that stated UMass Amherst was one of the first schools to protest the Trump election.

“Learning as an undergraduate about the history of protesting at UMass, it became like, ‘This is what we do here,’” Frisby said. However, Frisby mentioned that “there’s a lot more to do than just showing up” to protests, like mutual aid.

***

After an incident of a racially-charged hate crime in Meville Residential Hall in 2018, students protested the lack of acknowledgement and action from the University. Nuha Futa, a student at the time and an elemental organizer of the protest following the incident, feels as if she is experiencing ‘deja vu’ seeing students protest this year after racist emails were sent to Black organizations. Years after the incident, she reflects on the effectiveness of the protest and the consequences that followed.

Futa explained that the protests initiated conversation and forums regarding racism, one of their goals at the time. Futa now, however, expresses becoming disheartened on how effective conversations alone can be.

“Now that I’m older, I don’t know how impactful conversations are, but at that time, that was like one of our goals. And we thought we did that pretty successfully,” Futa said. She believes that undoing things people have learned in their upbringing before attending UMass is perhaps more critical for preventing incidents of racism on campus.

“I don’t think these conversations that the University is having, like forums and stuff, what is it doing for people? Like they should be implementing curriculum, like, required curriculum for people to learn about people that look differently from them,” Futa continued.

Futa stated that although the student body might be exceptional in its willingness to organize, she is hesitant to call the University itself revolutionary. Referring to the University, Futa said, “It’s also a business…their first goal is to make their money back….there’s a limit to, I think, how much you can do in a place like that.”

***

Although some students continue to question the administration’s willingness to respond to student protests, student activism has had a large role in changing University policy throughout history.

Before 1964, women on campus were under strict regulations. They were required to sign out every time they left their dorm and ask for permission any time they wanted to leave campus or have a friend visit. Curfews were also put in place. Freshman women had to abide by curfews of 8 p.m. until Oct. 15, while upperclassmen had to abide by less strict curfews. None of these regulations applied to the male students.

In the fall of 1965, students began organizing to protest what they considered outdated and discriminatory regulations. This outcry led to conferences, petitions, and student press and eventually the abolishment of sign-out sheets and almost all curfews. The new and updated student handbook for the year of 1966 read, “Curfews at the University are for the most part self-imposed by the student.”

African American professors and students pushed for the establishment of an Afro-American Studies department in the 1960s, as well. Schools were finally desegregated in 1954, making the number of Black students on campus only a fraction of the white students attending the University.

That group of both Black professors and students —there were only five Black professors employed by UMass by 1960— was responsible for the creation of UMass’ Afro-American Studies department. The group was able to establish a support network between themselves and ultimately share their common goals of better representation at the University.

The Black faculty members decided to ask the University for the establishment of the Committee for the Collegiate Education of Black Students, which was then created in 1968. The board strove to admit more Black students to UMass, and were successful in the University’s acceptance of 121 Black students. Later in 1970, the Afro-American Studies department was officially established.

In 1996, the W.E.B. Du Bois Library officially came to be with the initiative and leadership from Black faculty and students. There was resistance from many white students and faculty members, however, change was inspired and put into action through the efforts of representation by the Black community at UMass.

***

Students at UMass continue to struggle against those in power in the 21st century. The infamous Blarney Blowout in 2014 was followed by student protests, as students who had been celebrating the UMass tradition were met with excessive police force. After the event, students gathered to demand an apology from the Amherst Police Department, an investigation into the actions of its officers and that the town of Amherst sit down with student leaders to prevent such incidents from re-occurring.

Zac Broughton, a 2014 graduate and former Student Government Association president, participated in the protest and helped create the demands.

“I think we need to start talking about the story that isn’t being told, that students were treated like animals by police officers and that it’s unacceptable just because they’re students,” Broughton told the Collegian in 2014.

Following the protests, two of the three demands made by the students were met, only missing an apology from the Amherst Police Department. A 150-page report, including an investigation into what occurred on that day and steps to avoid such excessive force in the future, was published. This brought greater “legitimacy to the student cause,” Broughton explained.

“If it wasn’t for that protest, and the national exposure that it brought, I don’t know that an investigation would have happened,” Broughton said.

Drawing from his personal experiences and observations, Broughton described UMass as exceptional in terms of student organizing.

“UMass has always been, I think, a center of addressing important issues of the day. Students don’t shy away from doing that on a regular basis. And I think that’s what makes the campus so special and powerful,” Broughton said.

***

UMass has a long history of student protests that persists to this day, and University policy continues to change based upon student demands. Following the Be Revolutionary March, Chancellor Kumble Subaswammy announced the formation of a Black Advisory Council (BAC). The council will “provide the University with input and insight on how we can create a more supportive, just and equitable campus environment for our Black community,” he wrote in an email to students.

Subaswammy also issued a formal apology for failure to respond to the incidents quickly. Both action items were part of the 14 demands established by the UMass chapter of the NAACP, though many of those demands have yet to be met.

Student organization has also changed and adapted through time. McClaskey highlights the fact that students were allied by many faculty members in 1970, something that is not seen as commonly now. For change to occur, “Someone in position has to make some sort of statement, and it has to be in collaboration with the students,” McClaskey said.

Decades after her own anti-war efforts, McClaskey remembers asking her son, who was attending college at the time of the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, “Why aren’t you kids protesting?”

During the Vietnam War, images of death and war were being broadcast on television, and a draft was put in place that targeted anyone above the age of 18 — a reality not seen in the modern world, McClaskey explained. This made the students at the University emotionally impacted by the war and motivated to organize.McClaskey said that this generation of college students does not participate in anti-war protests as often because they are “completely separated” from the wars occurring at this time.

“It was our generation that was going to war there…It was personal,” McClaksey said.

McClaskey said, however, that she was inspired by the number of people that came together for the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020. “I had not seen protests like that for quite a while,” she recalled.

Although at times leaders and revolutionaries, students have always still been students — a reality that hasn’t changed since the beginning of student organization. Students in 1970 sometimes struggled to turn in their assignments in time, and worried about whether they would get a graduation ceremony. They sent letters to their teachers requesting a pass/fail policy because of the volatile social climate and their preoccupation with the strike.

Students may sometimes struggle to balance activism with academics, but Frisby shared advice for avid protesters on campus who may experience activism burnout: “Take care of yourselves,” Frisby said. “Be reflective of the ways that feel good to you to show up.”

Broughton also advises students who are currently protesting on campus. He highlights that just because every protest does not lead to significant changes does mean it is not valuable.

“My hope is that student leaders will continue to push university leaders and administrators for the changes they want to see,” Broughton said. “Student leaders need to also understand sometimes that winning doesn’t always mean getting everything you want…Sometimes winning is making progress.”

“But even if you don’t get everything you want, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t still keep fighting, right?”

Saliha Bayrak can be contacted at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @salihabayrak_.

Caitlin Reardon can be contacted at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @caitlinjreardon.