Irma McClaurin does not consider herself an archivist, but she understands the power in preserving Black history, especially after the decades-long efforts to erase it.

Initially moved by a desire to preserve her own personal documents and academic work, McClaurin sought to create the Irma McClaurin Black Feminist Archive (BFA), which now reside in the University of Massachusetts W.E.B. Dubois Library with the Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center (SCUA). The legacy project then became a mission to document the presence of other Black women.

“History is told through archives, if we’re not in the archives, then our history doesn’t become part of that American narrative,” McClaurin said. “So having a dedicated archive means we will not be forgotten.”

The collection stands as a dedicated archival space for the contributions of Black women and includes McClaurin’s own work and items, as well as that of other Black feminist anthropologists like Carolyn Martin Shaw. The boxes with McClaurin’s work are a compilation of her academic and personal life and include anything from personal letters, grant approvals, magazines on Black art, copies of poems, papers, books, and flyers collected through time, to a binder labeled “global Black feminism” and a course syllabus with “pizza party” scribbled into the class schedule.

“The materiality of our lives, and our whole lives, not just me as an academic, but as a mother, as a poet, you know, as a community contributor, all of that gets preserved in a way,” said McClaurin on her vision for the archive.

McClaurin is an anthropologist who looks at inequality at the intersections of gender, race, class and ethnicity. She is also a poet and has had a robust career in academia, having served as the first female president of Shaw University among many other roles.

“Many Black women of my generation, we were some of the first to go into predominantly white institutions. And I think about the fact that if something happened to me, my family would come in and look around this room that’s got folders and files and boxes. And they’d say, we just need to clean up this stuff,” McClaurin said.

Before McClaurin was recognized as a “Distinguished Alumni” and the collection was announced in 2016, McClaurin spoke with the late Robert Cox, who was the head of the SCUA at the time, to present her vision in the early steps of its actualization.

“I had someone at the library who understood the importance of it, and who supported me in sort of developing that vision,” said McClaurin on Cox.

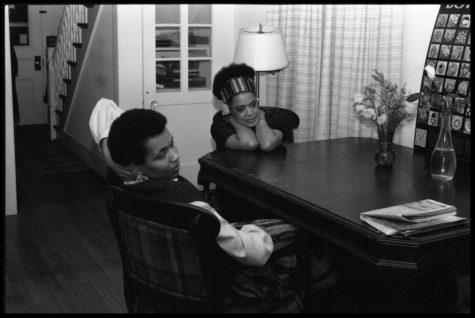

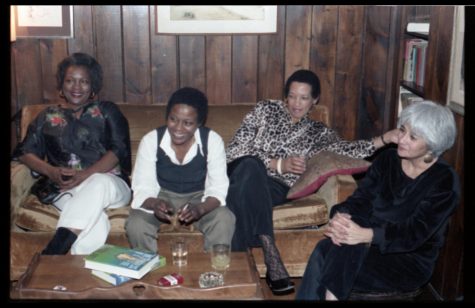

Along with the “Irma McClaurin Papers” and the “Carolyn Martin Shaw Papers,” the archives also include hundreds of rich photos that McClaurin has taken over the years, featuring trailblazers like Toni Cade Bambara and James Baldwin.

McClaurin is continuing to collect work and hopes for the BFA to be an expansive yet concentrated resource for those who are looking to tell the “fuller” story of the United States and the world. She also sees is it as an antidote to the burying or often too late unearthing of the contributions of Black women.

“I don’t want to see any more books about ‘Hidden Figures,’ I want us to be visible and heard,” McClaurin said.

Carolyn Martin Shaw also sees the documentation of her career as a reflection of social change, explaining that you get to “see a person engaging in ideas, how those have changed over time, and how that may or may not have been reflected in their lives,” through the archives.

Shaw is an anthropologist whose academic work focuses on African women in Zimbabwe and Kenya, often looking at the social values around virginity, purity and the impacts of colonialism on race, gender and class. When McClaurin began seeking individuals who were interested in preserving their work in the BFA, Shaw reached out to McClaurin, and together they began going through Shaw’s materials.

Through 10 boxes, the archives include her unpublished and published works, coursework from her time as a teacher, and personal items such as photographs. For Shaw, the personal items included capture “what it means to live and work as a Black feminist in the United States.”

“So the archives, personally, for me, was a wonderful moment for me to reflect on what I’ve done, and to be able to figure out what it is I’d like to share,” Shaw said. She also spoke to the general importance of the archives to “get a sense of what was the range and diversity of Black feminism” and to fill the hole that its absence would have created in our understanding of history.

Shaw’s time in graduate school and career as an academic began in the 1960s, a time when “studying women wasn’t something you wanted to do if you wanted to be taken seriously as a scholar,” Shaw said. However, the great expanse of her work covers the powerful contributions of women, their notions of themselves, and their efforts to push back against social and cultural norms. Their dreams, aspirations, desires and their display of power that are often viewed as “illegitimate” and may often be overlooked by anthropologists.

It was the experience of observing the women’s experiences in towns and villages in Zimbabwe and Kenya that made Shaw a feminist as the movement gained momentum, she explains, and made her realize that “women’s powers are so often unrecognized in anthropology, and unrecognized in their own societies.”

Shaw often aims to look at what is lost and gained in the interaction of colonialism and feminism. Through her field work in Zimbabwe, she observed in what was once a heavily family bounded society, women began to make greater contact with other women in their region through the means of new institutions such as school, churches and women groups after colonialism, and began understanding themselves as a class of women.

“Colonialism in itself is an oppressive system, but we are human beings and we have resilience…[we have to] ask the question about what under awful circumstances, what can people make of it?”

McClaurin’s work in anthropology began with her researching the suicide of the Black journalist Leanita McClain, looking at identity formation and the factors that shaped her death. Her work has also focused on the women of Belize, attempting to understand “What are all the components that go into shaping us to become women in a society? How are we complicit in our own subordination? How do we challenge it?”

McClaurin has an MFA in English as well as a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Massachusetts and has served in various administrative roles. McClaurin’s roots at the University, the activist atmosphere and the existing archives at the school all shaped her decision in considering UMass as a home for the BFA.

Danielle Kovacs, the curator of collections at the SCUA, spoke on the value of having documents of social change present at the University.

“UMass as a university itself has a long history of protests and demonstrations of students engaging in social change. And so, it feels very fitting to us that those collections which, even if they’re not specifically related to the history of UMass, would be part of our archives,” Kovacs said.

Kovacs also spoke on the wide audience that the SCUA has the hopes of reaching with their different collections of archives. “Our hope is that we’re not just appealing to academics and scholars, but that we’re appealing to our undergraduate students, we’re appealing to community members who want to engage with these stories, we’re appealing to young students in elementary school, middle school and high school who only know about history in history books without ever really interacting with the primary sources of those original documents,” she said.

The BFA is still in its early stages of development, and McClaurin is in the process of working with other’s interested in preserving their work. She ultimately hopes to have a BFA center in the future.

“I see my archive, as very much being on the forefront of making sure that that material is preserved, and then presented and made available to anyone, not just academics, but community people,” McClaurin said. “My goal is to make this the largest archive of its kind in the world, where people will want to come, and they will want to put their stuff in it. But they will also want to use it as a resource to tell a story.”

Saliha Bayrak can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @salihabayrak_.