Hosted by the Department of History at the University of Massachusetts, the 2022-2023 Feinberg Series, “Confronting Empire,” brought together scholars, journalists, educators, writers, community organizers and survivors of state violence to “examine global histories of U.S. imperialism and anti-imperialist resistance.”

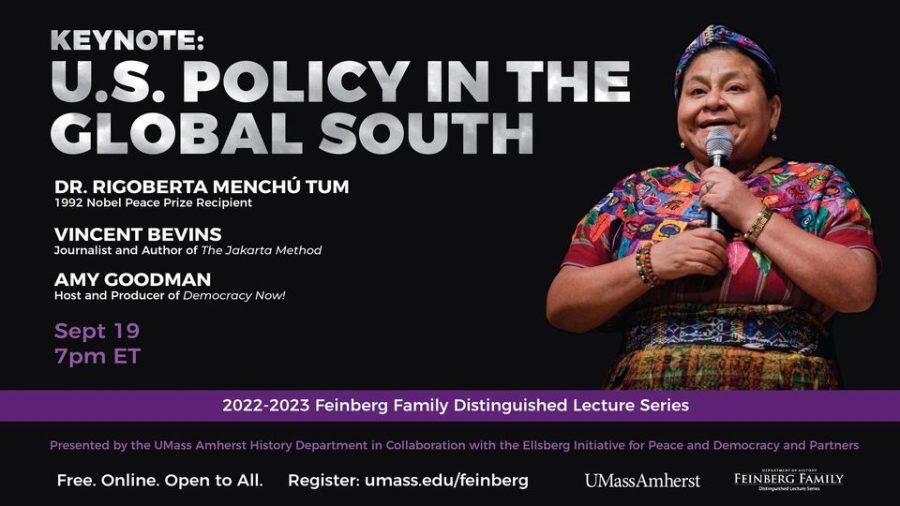

The keynote address, the first event in the year-long series, was highlighted by Nobel Prize laureate Dr. Rigoberta Menchú Tum, who won the Peace Prize in 1992 for her social justice work.

Menchú Tum had participated in the farmworker movement in Guatemala as a young woman, in which rural workers led movements against U.S. backed dictatorial regimes. She wrote “I, Rigoberta Menchú: An Indian Woman in Guatemala” as a testimonial denouncing the Reagan administration’s support for government attacks on Mayan communities.

“I am a social activist, and I think that’s the most important title I have because I was born in the struggle from the resiliency of the Indigenous people, from the vindication of human rights, the right to live,” Menchú Tum explained.

Menchú Tum detailed the risk that came with breaking her silence at the time. Her father was burned alive in the Spanish Embassy in the ‘80s, and her mother went missing after being kidnapped as result of her speaking out. “But my story is also a story that I could use to vindicate the collective memory of the Indigenous peoples,” she said.

Tum discussed how important it is to have a “historic memory” of the world. She noted how leaders like Henry Kissinger and Ronald Reagan, the former secretary of state and president of the United States, respectively, supported policies of terror in Latin America.

“At that time, everybody believed we were anti-American,” Menchú Tum said. “But we weren’t anti-American, we were only criticizing, and we were trying to visualize or civilize the policies that were hurting us within the framework of the Cold War…we wrote the history, the memory, because we don’t want the young ones, the young people to go through that again, to commit those crimes again.”

Menchú Tum does, however, believe we’ve come a long way. “We’ve settled some principles of struggle against violence. We’ve set some principles, some footprints for human dignity. We’re leaving history written in many different ways: verbal, written and in academic circles,” she said.

Menchú Tum was joined by Vincent Bevins, a journalist whose book, “The Jakarta Method: Washington’s Anticommunist Crusade and Mass Murder Program That Shaped Our World,” detailed the global history of U.S. terror against civilians during the Cold War.

Bevins said that following the end of World War II in 1945, we saw the division of the world into the First World, Second World and Third World countries.

“Now, at this time, at the end of World War II, the United States emerges as by far the most powerful country in human history,” Bevins noted. “It’s now the leader of the First World and this is a quick transformation for a relatively young country. The United States emerges onto the global scene with far more power than the countries of the Western Union that formerly colonized much of the globe,” he continued.

Bevins explained that the CIA failed in taking on the Second World and instead turned to the Third World, or the Global South, with a focus on Indonesia in the late 1940s to early 1950s. He detailed the “Jakarta Axiom,” which stated that early Cold War countries that stayed neutral and were not at risk of an immediate Communist takeover could be acceptable friends in the second half of the 20th century. The U.S. changed its policies towards Indonesia in the mid-1950s as the Communist party in Jakarta began to gain speed.

“We know now from declassified documents that even the CIA and MI6 knew that this was a moderate, unarmed Socialist party that had no intention of carrying out a revolution in the near future,” Bevins said. Regardless, the U.S. began a series of attempts to “derail” Indonesia’s anti-colonial structures.

Bevins detailed how the U.S. began to spread propaganda around the Indonesian Communist party, including blaming them for horrible crimes which never took place. They helped prop up a general, Suharto, who took control and executed around a million people, with another million being thrown into concentration camps. Once Suharto took power, however, Indonesia became an important ally for the U.S. in the Cold War.

Menchú Tum then discussed her going to the Spanish courts to force accountability for Guatemalan politicians and military members that participated in the destruction of Mayan people. “It’s terrible to think that to massively destroy something you have to strategize, right? You have to build a doctrine in order to then use it. And that’s what happened in the whole world and in Latin America in particular.”

Menchú Tum also mentioned what kept her going through her activism. “The biggest thing for me maybe was the rage I had in me for what had happened to my family. I tried to stay silent, but I couldn’t, and I made a huge effort to speak out,” she said. Those who did speak out did not worry about how long their pursuit of justice would take them, she added, it was a life-long struggle.

“I think if we stay as victims, if we think of ourselves as victims, we can’t take a stance against what we’re fighting against, what we’re struggling against. And I think the opportunity is important. I was given the opportunity to share spaces and speak out,” Menchú Tum said.

The address was moderated by Amy Goodman, the host and executive producer of “Democracy Now!”.

The Feinberg Family Distinguished Lecture Series is an event series offered every other academic year by the University’s Department of History, with funding from Kenneth Feinberg, class of 1967. The series “focuses on a ‘big issue’ of clear and compelling concern, generally a policy or social issue, aiming to ground it in historical inquiry, context, analysis and experience” the series’ biography says.

Alex Genovese can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @alex_genovese1.