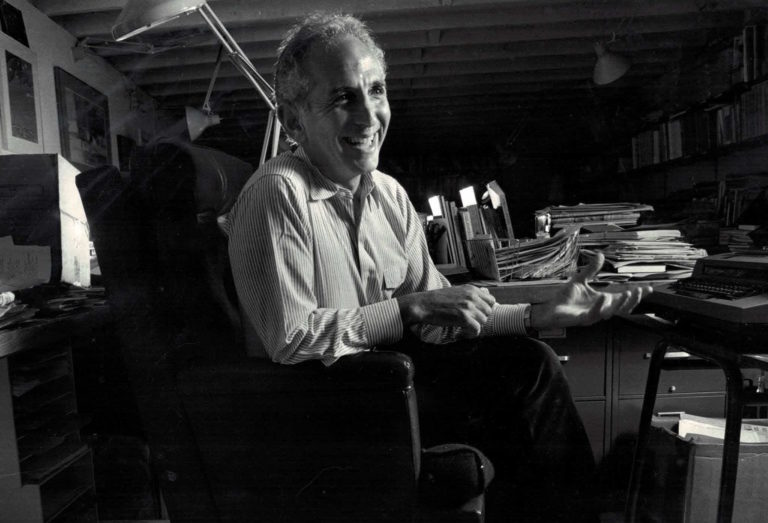

The Inaugural Ellsberg lecture opened with a short speech from professor Christian Appy of the University of Massachusetts Department of History. He detailed the goals for the lecture and the Ellsberg Initiative as one that would “promote public awareness, scholarship and activism on the overlapping causes that define Ellsberg’s legacy.”

Both the lecture and the initiative are named after Daniel Ellsberg, the whistleblower of the Pentagon Papers during the Vietnam War. Both the lecture and initiative seek to continue his legacy of which the Initiative describes as “peace, anti-imperialism, democracy, truth-telling, nuclear disarmament, and social and environmental justice,” according to the initiative. ”.

The main speaker for the Ellsberg Lecture was Azmat Khan, an award winning investigative journalist for the New York Times and the New York Times Magazine who specializes in reporting on the human costs of wars.

Khan detailed the history of America’s shift from sending troops to fight their wars to sending arsenals of aircraft, drones and precision weapons.

“There was a determination that if the United States was going to fight these costly wars abroad … we would try to minimize the harm to American lives,” she said.

Khan recounted her shock that civilian deaths were being reported so casually. “As the United States launched this campaign of airstrikes, I was reading headlines that said things like: ‘The airstrikes have killed 25,000 ISIS fighters,’” she said. An official report claimed that “only 21 civilians” had been killed.

She proceeded to describe a family in Mosul, Iraq and a man named Basim Razzo. Razzo woke up one night to find his family killed in an airstrike. A coalition led by the United States later released a video of the airstrike on Razzo’s home, which they had identified as an explosives factory. This was the video Khan showed the audience immediately before describing the death of Razzo’s family.

Razzo prepared a report of what happened to him and his family and tried to arrange a meeting with officials. While many believed him, nothing came of it. Khan met Razzo around this time and prompted an investigation into exactly how many Iraqis had suffered losses like Razzo.

“It dawned on him that the Razzo family’s fate was sealed by an hour and 45 minutes of completely unremarkable footage,” Khan said after obtaining and reviewing the documents detailing the strike on Basim’s family.

She also found that 50 percent of all civilian casualty cases were the result of poor or outdated intelligence. With the database of airstrikes and their assessments by the military, Khan began to match them to victim testimony instead of having them published.

In another case where surveillance was being conducted on an ISIS “bed down” facility, it was discovered that there were children on the roof of the building. The surveillance was sent for analysis and when it returned, something had appeared on the surveillance was redacted in the official report, shifting the building’s status from a bed down facility to a weapons manufacturing facility. This reasoning was enough to justify the strike, which would sacrifice the lives of three children to save countless other lives of those who could be harmed by the weapons being produced.

The redacted item in the report was later suspected to be a bread oven after Khan interviewed a survivor of the airstrike. “’I wish that it was a weapons manufacturing facility, because then their deaths would have been worth it,’” the survivor of the strike said, according to Khan. The official report claimed there had been one injury in this event. There were 12 deaths, but the official reports were never modified.

In another strike, Khan described children who were determined to be “transients,” or individuals passing by the area,but not being residents of it. A representative of the United States Agency for International Development was present and reasoned that the children lived there due to the country being in an active state of war. No one else agreed and 21 members of a family were killed as a result.

“In 2019, we dropped more bombs in Afghanistan than any previous year of that war and yet, that year, it received the least media coverage than it had on television news in the history of that entire war. The American public knows little of the wars happening in their name,” Khan said.

In the 5,600 pages of documents detailing more than 1,300 incidents Khan found, no accounts of wrongdoing or disciplinary measures were taken. Only one violation of the rules of engagement was found. In her findings, only two survivor interviews were conducted.

“It’s not the kind of overt lie where records are being concealed about how many civilians we’re killing,” Khan said. “It’s something that’s so much more clever in some ways, right?”

She also found that those in higher positions would use these documents to protect themselves from accusations of war crimes and expand the authority of the military to use their weapons.

“These civilian casualties were a major part of how the U.S. lost Afghanistan, but it doesn’t just matter on the strategic level, it matters on that moral level and it matters for an informed democracy,” Khan concluded at the end of the lecture.

“If we are to have a debate about our wars and to have the consent of the American public, they need to be informed about those wars,” she said.

Lily Harris-Hendry, a junior political science major, attended the lecture, and said it was “very impactful” and Khan was able to balance “finding and scientific methodologies that were used while also keeping it very emotional and touching.” She also expressed concern that there was “a lack of media and public awareness” about wars abroad that the American public is often misinformed about.

Henry Kleinrock, a freshman computer science major, also attended the lecture. “Anti-militarism is really important, and it’s an important thing for all students to be aware of,” he said. When asked what he took away from the presentation, he said he was interested in the journalistic practices involved in Khan’s investigation and how those can be used to obtain records and disseminate information to a wider audience about the actions of the military.

Diana Sierra Becerra, faculty member in the UMass history department and co-organizer of the Ellsberg Lecture said that the goal of this lecture was to “look at the human costs of U.S. warfare, aerial warfare and to center the dignity of survivors.”

“An air war in which we create that distance, not just from those whom we are targeting, but that distance in terms of our understandings, our reckonings, our ability to even keep it in the public consciousness,” Khan reminded the audience.

“All of that becomes more removed, it’s part of that human toll of our wars. It extends into our democracy and into our understandings of what happens in these wars,” she said.

Jeffrey Pham can be reached at [email protected].