Nearly three months after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled to overturn affirmative action, universities must now change how they factor a student’s race into the admissions process.

The 6-3 decision was spurred by two cases brought by nonprofit Students for Fair Admissions, challenging admissions at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina. The ruling concluded that both universities violated the equal protection clause outlined in the 14th Amendment.

Despite this ruling, the University of Massachusetts will continue to use a “holistic approach,” James Roche, vice chancellor for enrollment management, said.

“I don’t want to say I have no concerns, because we always have concerns when these kinds of changes present themselves,” Roche said. “However, I think that we’re in as good a shape as any university can be, because of what we put forward years ago.”

Since 2012, the University has employed an approach where factors such as standardized test scores and grades are considered along with an applicant’s life experience.

An exception in the ruling affirms the practice, as universities can still consider a student’s experience based on their race or ethnicity. Since then, UMass changed its application questions on the Common App.

“We realized that GPA and test scores were important, and they still are important, but they’re not everything when it comes to determining whether or not it’s a good fit for a student to be here,” Roche said.

Before his currently decade-long position at UMass, Roche worked at the University of Washington. Since 1998, UW has not used affirmative action in accordance with state policy.

“I came from a process where we couldn’t consider race or ethnicity, and I think most of the folks in admissions anticipated that someday this would happen,” Roche said.

Aside from UMass’ changing admissions process in 2012, the year also served as a turning point when the University application pool started to increase.

In response to the rise in applicants, the admissions team began to strengthen their relationship with community-based organizations (CBOs), nonprofits that provide academic support and preparation for high school students.

High schools throughout Massachusetts can partner with different CBOs. A few of the most common ones in the state include Upward Bound and “GEAR UP,” with locations from Holyoke to Lowell.

Like Roche, first-year admissions counselor Erin Bernard has worked at UMass for over a decade.

“The pandemic kind of put a wrench through our recruitment, so we haven’t had as much interaction probably in the last three years as we did before that,” Bernard said.

While UMass is the largest public university in the state, it is not representative of Black or Latino high school graduates in their state.

Nearby cities like Springfield, Massachusetts have large Black and Latino student populations, as shown in enrollment data for Springfield High School. In the 2022-23 academic year, Black students made up 16.7 percent and Hispanic students made up 69 percent.

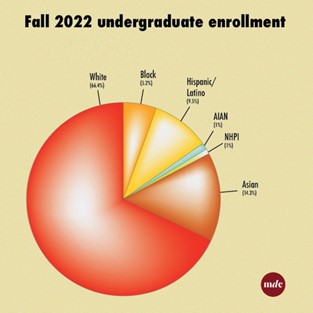

When looking at undergraduate enrollment data from University Analytics and Institutional Research in fall 2022, Black students made up 5.2 percent and Hispanic/Latino students made up 9.5 percent of the undergraduate population.

Students that identify as Native American make up one percent of the population at UMass. College demographics are also less likely to represent these students.

Afro-American studies graduate student Makhai Dickerson-Pells, who identifies as part of the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe, holds concern for future classes.

“From some students I’ve talked to, a few of the bigger issues for them are around affordability, or having their family depend on them to some degree, so it’s a little harder to be away from home,” Dickerson-Pells said.

The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe is one of two federally recognized tribes in the state.

Prior to his arrival at UMass, Dickerson-Pells was not aware of the culture shift that students like him, an Afro-Indigenous male, would experience until he was on campus.

Charlotte Gilson, a junior sociology major who plans to attend medical school, had closely followed the SCOTUS case leading up to the decision.

“I wasn’t surprised, but at the same time I was very shocked and upset,” Gilson said.

Gilson comes from a family of doctors and physicians, where relatives served as role models in her life. Having an interest in health equity, Gilson recognizes the disparities minorities face in the healthcare system and their lack of representation in the medical field.

“It’s kind of an interesting juxtaposition where I have my family and all of these really strong, powerful Black doctors, and then when I’m in school, or even working in a hospital, I see the demographics of who is in charge, and most of them aren’t Black,” Gilson said.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, Black medical school graduates are underrepresented.

Gilson recalled the experience her grandmother, a former pediatrician, had in an interview for medical school.

“The person interviewing her said that her resume and credentials were ‘better than most of the White boys applying,’ but they couldn’t accept her,” Gilson said. “They told her, ‘We’re not in a place right now where we can accept a Black woman.’”

Since the late 1970s, challenges to affirmative action policies have been “really broad,” Paul Collins, a legal studies and political science professor, said.

Collins researches judicial policymaking at UMass and described how a 1978 case involving the University of California was the first Supreme Court case to rule in favor of affirmative action.

“Really what you saw in response to that, in large part, was a movement by conservatives to target affirmative action,” Collins said.

A large political effort in Michigan barred the use of affirmative action at the University of Michigan via a ballot initiative in 2006. Administrators struggled with diversity efforts shortly after, as noted in an article published last year in The Michigan Daily.

Roche said that he does not see the ruling affecting UMass more than selective schools.

“As long as students understand that their chances of being accepted here are as good as they were before, then we should not see much of an impact,” Roche said.