“The Drum,” founded in 1969 by University of Massachusetts student Robin Chandler, was an annual student publication chronicling the Black literary experience. The magazine included poems, essays, visual artwork, interviews and current event coverage. It had offices located in the Black Cultural Center in Mills House, where the New Africa House is now located.

The Daily Collegian wrote in September 1987 that because “The Drum” did not publish in 1977, students “appealed for a class that would help organize the magazine’s production.” The class Contemporary Black Image Making, was taught by Professor Nelson Stevens and focused on producing “The Drum.”

Between 1984 and 1985, the Student Government Association (SGA) pulled funding from “The Drum,” saying that the magazine being edited in a class violated SGA bylaws. Stevens disputed this claim, maintaining that the class was essential to the publication and that his role was merely an advisory one.

SGA claimed that “The Drum” violated other SGA bylaws, saying that the magazine did not submit a biannual constitution, only accepted “third-world members,” much of the magazine was not written by students and that only 500 of 4000 issues were distributed on campus in 1986.

Stevens disputed all of these claims, saying that “The Drum” did submit constitutions, that their two most recent presidents were white, that students chose and reviewed all material in the magazine and that “The Drum” advertised on WMUA telling students where to pick up the publication.

Following SGA defunding, Chancellor Joseph Duffey’s office funded “The Drum” until 1988, when publication ceased. Its relative successor was Nommo, a Black culture magazine that began publication in 1990.

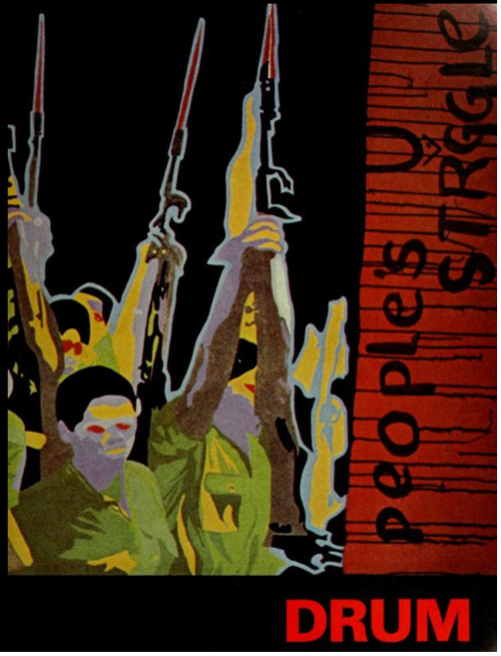

“The Drum” was founded in the midst of the Black Power movement, a revolutionary movement in the 1960s and 1970s that not only emphasized Black economic and political empowerment, but also Black literary and artistic expression. Kathy Forde, a professor of journalism at UMass and a historian of the press, sees the creation of “The Drum” as the UMass student body’s embrace of this movement.

“[‘The Drum’] was really for the students and by the students on our campus, being activists at a predominantly white institution to create space for themselves and inclusion for themselves,” Forde said.

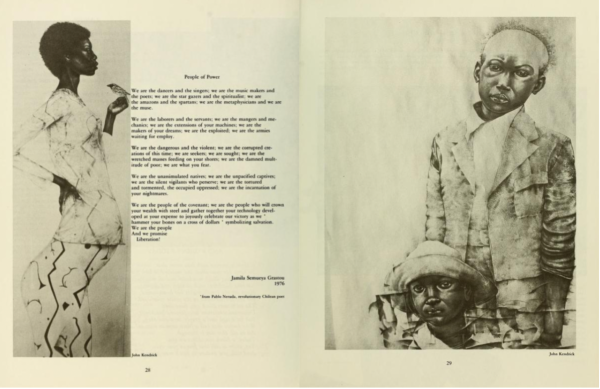

Forde also sees “The Drum” as an important historical document of the time, recording Black student activism on campus, like the push for the establishment of the African American Studies Department and support of the occupation of the Mills House. “As a historical record, it’s meaningful,” she said, “and as a record of the literary, artistic and journalistic aspirations and expressions of the time, it’s important.”

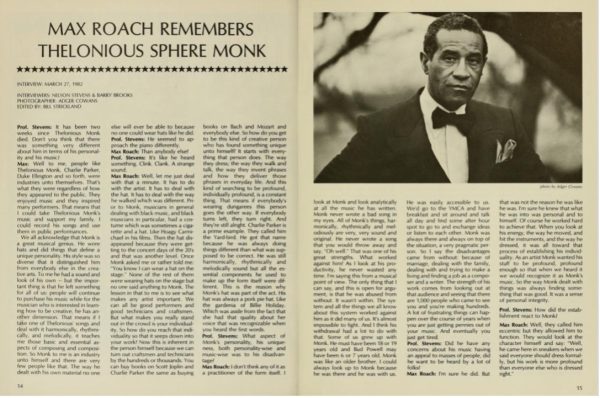

The Black artistic movement of UMass flourished during “The Drum’s” run. In 1971, Chancellor Randolph Bromery was hired, the first Black chancellor in UMass’s history. Bromery established the Fine Arts Center at UMass, and during his time as chancellor, jazz legends Max Roach, Archie Shepp and Fred Tillis joined UMass faculty. This led to the creation of UMass’ Jazz in July program, a popular summer intensive program on jazz improvisation.

“While there were other communication and literary organizations on campus, including the Collegian and a couple of literary magazines, they did not really fit our needs, and some students had in prior years gone through rejection — their works weren’t accepted or worthy,” Dr. Carlton Brown, a co-editor of “The Drum” when it was first established, said.

“So we knew that it was important to develop a magazine specifically aimed for African Americans to both reach them,” he continued, “affirm their worth, provide an outlet and a mechanism for their art and their expression and their thoughts and their ideas, and reflect that back to them for the sake of building culture.” He recalled that he only knew Chandler for about a month before she pitched the idea of the magazine to him, but they got to work immediately.

Finding funding proved difficult at first, however, with the SGA denying their initial request. But the students persisted, and eventually received funds after returning with additional support. “For whatever reason, those people that constituted the so-called elected officials of the Student Government Association did not see the value of what we were talking about. And my only point that night was it doesn’t matter that everybody sees [the value], it matters that the population in question sees the value,” Brown remembered.

“The Drum” was inextricably linked to multiple other movements on campus at the time. Many students who were involved with the magazine were also involved in establishing the Afro-American Studies Department. Brown recalled his experience working with Steve Moore, a student leader shot by police during the Orangeburg Massacre — a series of protests that ended in the deaths of three South Carolina State students, with dozens of others injured. Once Moore was out of the hospital, Brown brought him back to his apartment in Amherst to recuperate, and they began talking. “He and I immediately became engaged with pushing for the African American Studies department,” Brown said, “so all of that was happening at the same time. And so, it’s a very intense time period.”

In 1970, “The Drum” also printed the statement in support of the occupation of Mills House, “We, the following black students feel that there is no black culture unless we live it. Life is culture. Culture is life. We cannot visit that culture and be a part of it.”

In February 1970, Black students barricaded themselves inside of Mills House, then a dormitory building in the Central Residential Area. This came after a fender bender involving a Black student residing in the dorm and a white student living in the fraternity house across the street escalated into a full-blown altercation between the white fraternity members and the Black residents.

Several members of the fraternity chased the group of Black students into Mills House. After kicking out the white residents and barricading themselves in, the students put forth a list of demands that included the establishment of an Afro-American Studies Department and the repurposing of Mills House into the Black Cultural Center, now the New Africa House.

Although “The Drum” is no longer active, there are other student-run publications on campus dedicated to highlighting marginalized voices.

“Obviously the journalism field is still very predominantly white, so just having that space for students to be able to come out and write and feel comfortable and see other people who have experiences like them and also have the same passions is very important,” Christmaelle Vernet, editor-in-chief of The Rebirth Project, said. The Rebirth Project offers opportunities for students of color to pursue both journalistic and creative writing. Founded by Ramona East in 2016, it was intended to be a revamp of “The Drum.”

As for the future of The Rebirth Project, Vernet emphasized the importance of having a “third space” for students of color to come together and write. “I just hope that it’s still here in the future and students know that it’s an option for them,” she said.

Sophie Machernis can be reached at [email protected]. Luke Macannuco can be reached at [email protected].