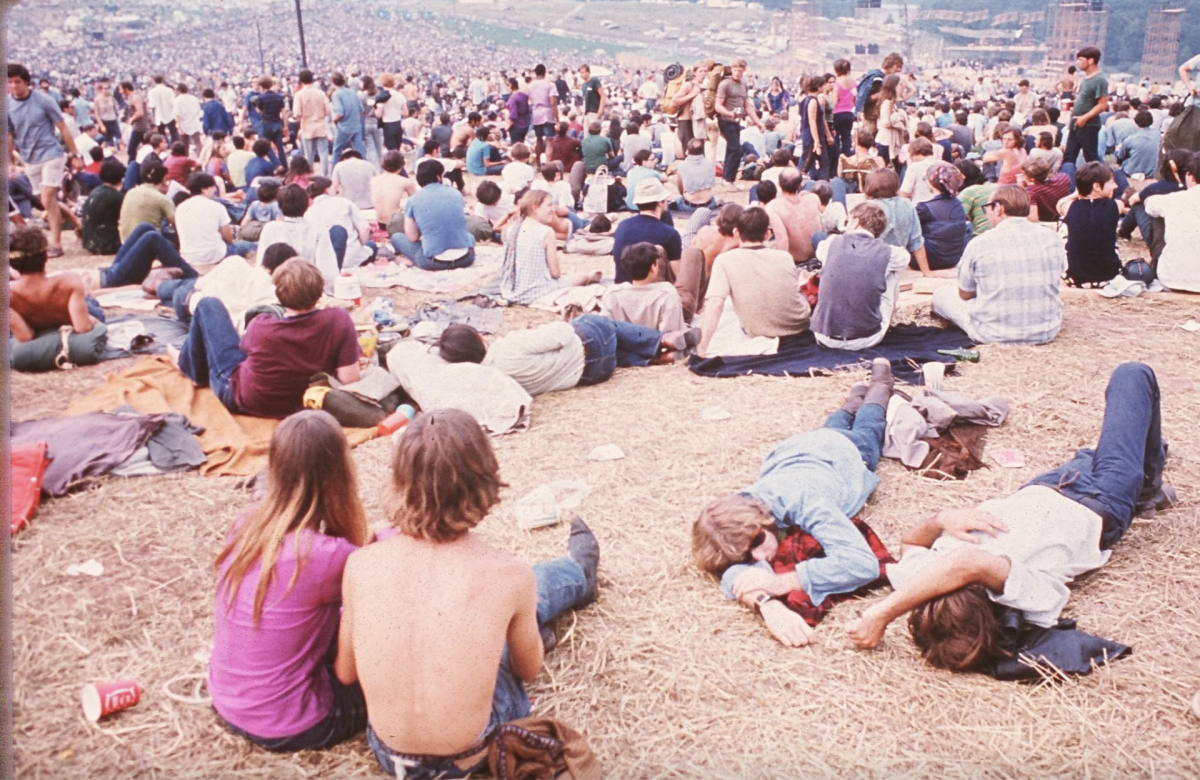

With the summer festival season underway, it’s easy to reflect on major music moments like Woodstock, Burning Man, Glastonbury and more. While many of these names have become household ones in the world of music, not many would know the name of Woodstock’s forgotten co-competitor and San Franciscan-born imaginary. Here’s a brief history of the Wild West Festival, and the whisperings of its quiet unraveling.

During the late 1960’s, San Francisco was at the forefront of an impending societal change. With the ideas coming out of the city being centered more around creating a communal lifestyle, an endless number of methods to achieve this goal were realized.

The constant output of artistic creativity led to the organization of a festival known as Wild West, that in the words of renowned jazz critic Ralph Gleason, had “the potential to change the world.”

The expectations for the event dwarfed even those of the upcoming Woodstock festival, to the extent that some outlets were referring to this cross-country counterpart as “Wild East.” But Woodstock would go on to become the defining moment of the 1960’s zeitgeist while several insurmountable issues arose during the planning of Wild West, leaving it an abandoned pipedream of San Franciscan counterculture.

On March 12, 1969, a group of influential members of the music industry — ranging from Grateful Dead manager Rock Scully to the band’s LSD manufacturer Owsley Stanley, as well as concert promoter Bill Graham, co-founder of Rolling Stone magazine Jann Wenner, Jefferson Airplane manager Bill Thompson, among others in the field — gathered at Jefferson Airplane’s mansion outside of Golden Gate Park. The eccentric collection of talent would then form the San Francisco Music Council, a group that believed countercultural methods were the most effective way to create new social, economic and political structures.

Out of this belief, a plan for Wild West was created.

The festival’s purpose sought to bring people from all walks of life together in a free-thinking setting — and the organizers knew they couldn’t limit themselves to simply hosting a rock-and-roll concert.

Wild West, as the name suggests, was to be a creative free-for-all hosted in the counterculture capital of the nation. It was designed to present music of multiple genres as well as theater, dance, puppet shows, circus acts, hayrides and many more attractions to appeal to as wide a range as possible.

The proposed strategy to raise funds was through three admission-only concerts, and to encourage performers to offer their services for free in exchange for a part in an event seemingly destined to change history. Some artists did initially agree to perform for free, but problems began when they started to raise questions about why festival staff and organizers were being given a salary.

One aspect of Woodstock that cemented its legacy in counterculture history was that the organizers were content to operate at a $1.3 million loss in exchange for eternal cultural impact. While their counterparts in San Francisco preached the importance of art over money, they could not stomach this trade off. They claimed to be focused purely on the culture, but it was clear that turning a profit was a significant motivating factor for many members of the group.

Another obstacle that soon became apparent was resistance from local members of the counterculture. Though the San Francisco Music Council claimed they represented the people of the area, the citizens themselves banded together to create what was known as the Haight Commune. The group argued that they actually spoke for the general public and claimed the council excluded multiple marginalized demographics from all aspects of the festival.

In addition to this specific concern, the Haight Commune objected to the concept of Wild West as a whole, claiming it was just “another cultural rip-off.” While the Wild West organizers claimed to be focused entirely on artistic exploration, the commune believed they were yet another group looking to capitalize on the increasing popularity of hippie culture.

This may or may not have been the truth, as many of the event organizers were firmly ingrained in the counterculture themselves. But once the idea took hold, it became the main focus of the festival’s opposition. The hip youth that were supposed to comprise much of the audience had quickly soured on the idea. As financial struggles continued to plague the music council, the increasing resistance loomed large.

The planners were determined to move forward with the festival even while facing these obstacles, until protesters went so far as to suggest that violence may take place at the festival, and directly threatened one member of the San Francisco Music Committee. After this, discussions were permanently shut down.

On Aug. 13, 1969, nearly five months to the day after the initial meeting, Wild West was canceled – and just two days later, Woodstock would introduce the world to “Three Days of Peace and Music” in what would become the defining moment of an entire generation.

JD Hildreth can be reached at [email protected].