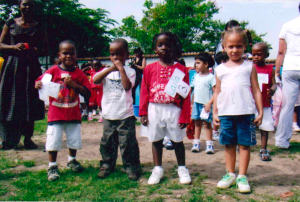

“There are beautiful, beautiful places everywhere in Congo. It’s one of the largest [forest] reservations, there’s [just] so much good in the country,” Leila Imani, a senior biology major born and raised in Congo for 11 years, said.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (Congo) is located in Central Africa and is known for its large reserves of minerals and resources along with its extensive music and food industry. The country has the world’s second largest rainforest, the Congo Basin, and features over 250 known ethnic groups and languages.

“Our music and our food are unmatched,” Joy Kunda, a communications and journalism double major who moved from Congo when he was 12, said.

For David Kakule, a computer science major, the way his people communicate is one of his favorite parts about being Congolese. “In the many shared and tribal languages we use, there’s so much emotion and expression that breaks through the words; there’s certain sounds we collectively use [that] is heard in our speech and our music,” Kakule said.

Imani’s mother was an established doctor in Congo but faced challenges trying to practice in America due to the U.S. not accepting “certifications from countries that they consider ‘third world.’” To avoid those issues, her family moved to America when Imani was younger so Imani and her sister could pursue their careers without these difficulties.

“I started identifying more with overall Blackness rather than my ethnicity … race wasn’t something I really thought about when I was in Congo,” Imani said. Once she realized she would live life through a racialized lens, she has been trying to reconnect with her homeland more.

The area Imani moved to did not have a large Congolese population either, and she said that most people assumed her ethnicity as either Black American or Haitian. Many did not even know Congo existed, which led to her frequently having to explain her identity.

“I felt like I was Congolese at home and Black American everywhere else,” she said.

For Kakule, being Congolese is “to be a person that brings joy to the community in your life, whether little or small.”

“This place has birthed so many customs and has connected me to some of my favorite people, including my cousins and many other Congolese friends,” he said, adding that the people are compassionate and “love deeply in their circles.”

Although Kunda has a deep sense of pride in his country’s natural beauty and cultural heritage, he highlighted that being Congolese also involves acknowledging the complexities of the nation’s history, including its “struggle for independence,” and the ongoing issues of “political instability, corruption and resource exploitation.”

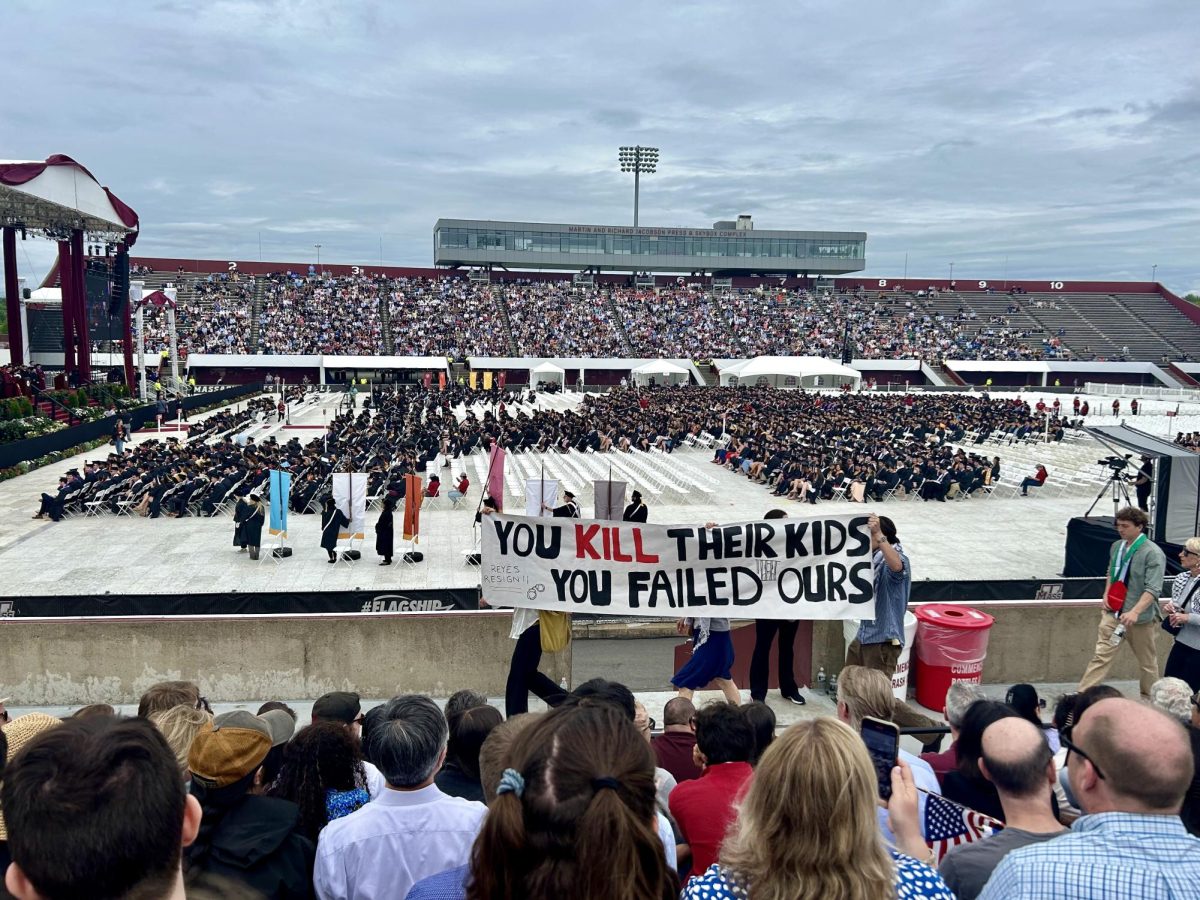

Currently, Congo has been the site of a 30-year long conflict with a series of rebel groups, following mass emigrations from neighboring Rwanda after the 1994 Rwandan Genocide. A recent surge in the war with the group M23 has resulted in the displacement of 6.9 million people in the nation of 99 million, with many being subjected to sexual violence, killings and other war crimes.

Due to their resource-rich reservations, Congo has also been exploited by large corporations, especially for their cobalt and copper reserves, often used in making electronic components like rechargeable batteries. The Congolese people have faced numerous human rights abuses in this process, including forced evictions, child labor law violations and sexual assaults.

In March 2022, a case was brought against the five tech giants: Apple, Alphabet Inc., the parent company of Google, Dell, Microsoft and Tesla. Plaintiffs claimed the companies “knowingly benefiting from and aiding and abetting the cruel and brutal use of young children in the Democratic Republic of Congo to mine cobalt.” All five companies were absolved of the charges in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

Imani has lost two family members due to the ongoing conflict. When she was studying in Congo, there were a lot of violent protests near her school, creating safety concerns.

“It is a pain that I’ve been carrying around with me … it’s kind of just like having a cloud upon you that nobody else can see,” Imani said. When she thinks of her country, she often reminisces about the joy of being there, but she also thinks about the personal losses she incurred — a burden she tends to carry alone.

“I was just surrounded by all of my culture, my languages, my food, everything that makes my people who they are … and now that I don’t have it, it’s something that I really feel like missing,” Imani added.

When Kunda was a child and still in Congo, he remembers watching the news about the mass displacements and reemergence of the war but didn’t know much about it. His family lived in Kinshasa, in the western portion of the country, while most of the conflict was present in the east.

“Despite being wealthy in natural resources, Congo remains one of the poorest countries based on GDP; it’s heartbreaking to see the rising death tolls and to feel like there is no hope,” he said.

The ‘War on Congo’ has left some of Kakule’s family “scarred beyond words.”

After hearing about ‘gruesome’ outcomes of his other family members or friends back home, many Congolese immigrants in America have expressed a “desire for the situation in the DRC to change,” Kakule explained. He has not been able to visit Congo due to these dangers.

There are many ways people can aid Congo in their struggle, the students mentioned. Acknowledging how the world has benefited from the “suffering” of Congolese people is the first step, Imani explained. Consuming responsibly- buying technology secondhand or waiting to purchase new products until absolutely necessary- is another example.

Donations towards charity organizations, like Friends of the Congo, would help raise awareness as well according to Imani. All this awareness should be done carefully, however, to not “vilify” the nation or push the idea that “third-world nations are war torn and decrepit,” Imani said, adding that in their advocacy, people should emphasize the beauty that exists in Congo as well.

“It’s not bad to use natural resources, it’s just horrible in the [exploitative manner] that it’s done,” she said.

Kunda said a ‘Free Congo’ is one where the country’s natural environment is safeguarded for the future, accountability for political officers exists and Congo’s younger generation has access to fundamental rights like education and healthcare. “A free Congo for me is a nation where justice, freedom and dignity prevail for all citizens,” Kunda said.

For Kakule, it is when child labor is “no longer a standard” and where resources are “fairly exchanged with other countries.” He added, “[A free Congo] looks like a place where all the villages are treated correctly and the borders are open.”

“Being Congolese involves a determination to fight for justice, freedom, and dignity for all your fellow citizens. It means carrying the spirit of your homeland with you wherever you go, even as you adapt to life in a new country,” said Kunda.

Mahidhar Sai Lakkavaram can be reached at [email protected] and followed on X @Mahidhar_sl.