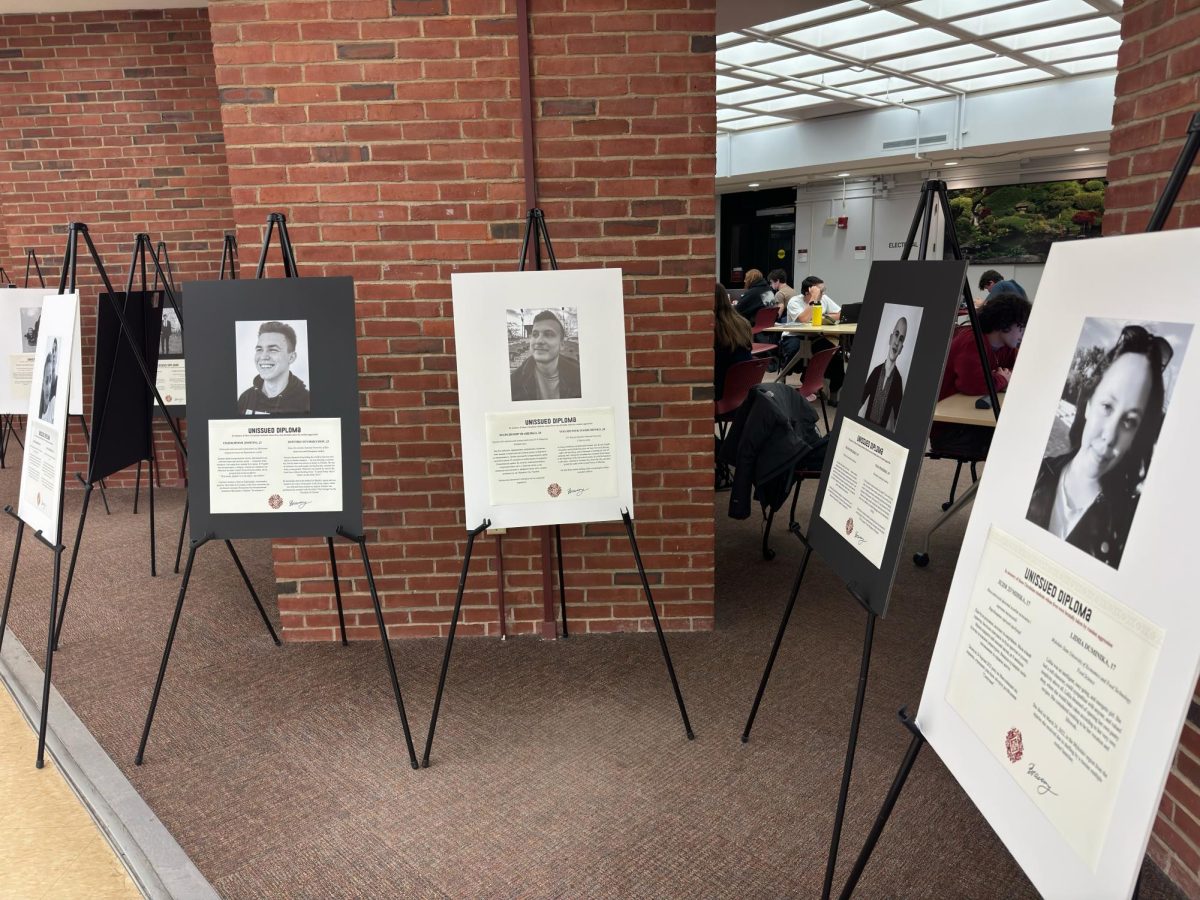

On Friday, April 26, the W.E.B. Du Bois Center hosted “Scissors, Silhouettes and Stencils: Yolande Du Bois’s Artistic Imagination.” Facilitated by Phillip Luke Sinitiere, historian and professor of history at the College of Biblical Studies, the event unveiled never-before-seen images and excerpts from newly discovered scrapbooks of Yolande Du Bois’ life.

Throughout the event, Sinitiere emphasized Yolande Du Bois’ identity as a visual artist and its separation from that of her father, W.E.B. Du Bois, a pan-African civil rights activist, and her ex-husband Countee Cullen, a nationally known poet of the Harlem Renaissance.

“The overwhelming impression that we have today…is that history acted upon Yolande Du Bois, rather than Yolande Du Bois making her own history, writing her own story, painting her own canvas, or if you like, dancing on her own stage,” Sinitiere said.

The eight scrapbooks arrived at the University of Massachusetts a year prior, three of which were present at the event. They were purchased at an auction storage unit in Portland, Texas.

Sinitiere detailed how the books were left behind by Du Bois Williams, Yolande Du Bois’ daughter, as she moved across the Texas Gulf Coast. The articles survived 50 years through various extreme weather conditions, including freezing and drying cycles with significant temperature changes, flooding, hurricanes and high humidity, marks of which can be seen on the pages and covers.

“[The scrapbooks] are the keys to unlocking Yolande Du Bois’ artistic imagination as a visual artist, as a writer, as a curator of photographs, as a storyteller…we start to understand and see [her] speaking in her own voice, on her own terms, in her own way,” he explained.

Most information known about Yolande Du Bois was primarily through the two biographies of her father, written by David Levering Lewis. Sinitiere believed that Lewis “inadvertently adopted” W.E.B. Du Bois’ opinion of his daughter, viewing her as a “cagey teen competing for her father’s attention” or as “self-indulgent [and] underachieving.”

In other works, Amy Helene Kirschke described Yolande Du Bois as “an amateur artist of limited talent,” while Tara Green in “See Me Naked: Black Women Defining Pleasure in the Interwar Era” compels readers to consider Yolande Du Bois as a person outside of the “towering shadow” of her father.

“These eight scrapbooks, several of which are in our presence today, challenge this perspective and call us to think about [and] consider a much broader, more nuanced [and] enhanced perspective on Yolande Du Bois as a person behind [the] artist,” Sinitiere added.

This work, in addition to the discovered scrapbooks, made Sinitiere question who Yolande Du Bois truly was. He dove through numerous archival collections and historical evidence of her life’s work to find these answers, following which he integrated the scrapbooks into the study.

Evidence of Yolande Du Bois’ artistic expression is first seen when she’s a young teenager, where a Thanksgiving card from 1911 showed a small sketch of a rabbit from Alice in Wonderland. Her distinctive art and writing style are developed through the years, as her lettering starts featuring a slanted lowercase “y” and her sketches show a prominent “young doll-like” figure, both of which were seen in her scrapbooks as well. Sinitiere noted that her personality started to slowly show through her artwork over time.

“The scrapbooks chronicle her life visually and sort of artistically from her mid-teen years to about age 30. And it’s not just the fact that these scrapbooks exist, these scrapbooks tell a story, they tell many stories,” he added.

After highlighting other archival evidence of Yolande Du Bois’ life, including greeting cards she made as a child and photographs throughout her education, teaching career and marriage to Countee Cullen, Sinitiere delved right into the contents of the scrapbooks.

The scrapbooks helped Sinitiere piece together numerous parts of his study. For instance, he had seen mentions of “Steve” in different manuscripts, one even being a eulogy to this figure from W.E.B. Du Bois in the Crisis Magazine. The scrapbooks had photographs of a family dog named Steve, which helped Sinitiere realize that this was who W.E.B. Du Bois was referring to. This scrapbook evidence unlocked many of the Du Bois family’s stories, Sinitiere emphasized.

During the Harlem Renaissance, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) started the Crisis Magazine and its children’s issue, The Brownies’ Book.

In The Brownies’ Book, Sinitiere saw “more of Yolande [Du Bois’] art and artistry [come] to the forefront.” While she had written numerous stories, Yolande Du Bois’ illustrations in her signature style were seen throughout the editions.

“As I made my way through the scrapbooks, I was able to put side by side some of the stenciling and lettering, the kind of stylistic script that Yolande [Du Bois] made in The Brownies’ Book and compare that to what I found [in] the scrapbooks.”

By doing so, Sinitiere discovered that Yolande Du Bois even stenciled section headings in the issues of the book, finding her distinctive lettering such as left-leaning capital letters and even the previously mentioned “doll-like figure.” With this evidence, he could argue that some of the other illustrations were also done by Yolande Du Bois despite there being no attributions. He emphasized how involved she was in these publications, all while being a graduating high school student.

In Crisis Magazine, he saw that she solo-illustrated the cover for only one of the editions. However, her distinctive lettering and images are dispersed throughout various articles in each edition, especially her illustrations of female figures and landscapes. During the event, Sinitiere passed around copies of different editions that Yolande Du Bois contributed to.

Yolande Du Bois’ artistic style expanded to include geographical illustrations and using silhouettes much more prominently. In a scrapbook from her time at Columbia University, Sinitiere saw a clipped story of hers from the Crisis Magazine — which had the same stenciling — but he didn’t know which issue it was from. He eventually found it in a January 1925 issue of the magazine, but as he looked through it more, he started noticing her silhouette drawings in a variety of articles.

“I realized that Yolande [Du Bois,] in addition to many of the other artistic expressions we’ve been talking about, is a [silhouette artist.] And often these silhouettes would appear alongside points for literary reflections… [they were] connected to literature,” he explained.

The silhouettes were often singular and female figures, with them doing various outdoor or physical activities, like jumping and skating. “[It’s as if] Yolanda was using this shadow art to make herself more visible… so I think there’s a conversation going on here, maybe we can view these as a form of resistance, maybe we can read these as a form of self-expression,” he added.

“From scissoring scrapbooks to stencils [and] silhouettes, we have encountered what I hope is an interesting and illuminating [artistic journey],” Sinitiere concluded. Many of the scrapbooks’ contents are currently being digitized so they can be made publicly available.

Mahidhar Sai Lakkavaram can be reached at [email protected] and followed on X @Mahidhar_sl.