Blake Frohnapfel stands several yards behind his center in the shotgun, as he’s done many times before.

Stationed directly to his left is a running back. To his far left are three receivers lined up in a trips formation, heads cocked and eyes peered directly into the backfield, almost beckoning for him to snap the ball. One receiver flanks to the right.

Marshall trails ECU 42-38 with 11 minutes, 22 seconds remaining. The season proverbially hangs in the balance as the Thundering Herd entered the final contest of 2012 needing just one more victory to become bowl eligible and prolong the season.

Frohnapfel calls for the snap and pivots, his running back shuffling right in preparation to take a handoff. An ECU defensive lineman clad in all-purple eludes his blocker, eyes pinned to the exchange orchestrated by Frohnapfel. His stare never leaves this defender. He pauses, waiting, carrying out a textbook read-option handoff.

He pulls the football back, allowing his running back to slide by. The defender follows and the line crashes on the running back. The linebackers trail the running back, distracted. Frohnapfel, who is wearing all white with green trim, darts left – only it’s not so much a dart as it is a succession of choppy steps – and he takes off. The television camera’s as fooled as the ECU defenders and pans toward a scrum of bodies at the line of scrimmage.

The ball isn’t there, it’s with Frohnapfel.

He’s 20 yards past the line by the time the camera recovers, Frohnapfel strides toward the end zone. At about the 25-yard line his body lurches forward, his feet struggling to stay under his upper body. But he steadies, pushes on and isn’t touched. It’s a perfectly executed play, as if he’s done it countless times before.

Frohnapfel has just run for a 51-yard touchdown, the longest allowed by ECU that season. He’s put his team ahead 44-42. He finished the game – one Marshall eventually lost 65-59 in double-overtime – with 163 total yards. It’s his best performance to date as a college quarterback.

He celebrates in the end zone in a manner suggesting that end zone celebrations are uncharted territory. Frohnapfel scans his surroundings for others to take part in the fun as his arms move without any particular pattern, similar to an inflatable mascot outside a car dealership.

It’s a moment that, two years later, Frohnapfel can laugh about after a Massachusetts football practice at McGuirk Stadium. He laughs because it’s an admittedly poor performance but laughs because he’ll hopefully have more chances to carry out more touchdown celebrations.

Something he couldn’t do at Marshall.

‘This kid’s got a pretty good arm’

Steve Frohnapfel knew exactly what his 2-year-old twin sons – Blake and Eric – would enjoy on Christmas morning – a small, soft baseball and baseball glove.

An avid sports fan – college football and, more specifically Notre Dame, hold a special place in his heart – he wasted little time introducing Blake and Eric to a variety of sports. Despite having baseball in mind, he quickly discovered a potential quarterback living under his roof.

“Blake took the ball immediately,” Steve said. “And he threw it the length of a 20-foot living room and hit me in the face. And I thought ‘this kid’s got a pretty good arm.’”

By the time Blake and Eric were 8 years old, their father knew he was blessed with two talented athletes. Blake dabbled in other ventures – he was a pitcher and a point guard on his pee-wee basketball team – but football quickly became the favorite.

Steve would return home from work and throw passes in the front yard of his Stafford, Virginia, home to both Blake and Eric to “wear them out.” The trio returned to their own personal gridiron on Saturdays too, sneaking out at halftime to throw the ball while whatever college football game that happened to be on television was at commercial. Occasionally, Steve would match Blake and Eric up one-on-one.

According to Blake, it was those sessions in the yard that spurred his football career.

“That’s actually probably why we’re so competitive,” he said. “It’s where I learned to love the game, during those times in the front yard.”

Soon, Blake would be the one throwing the passes. And quickly thereafter, he was doing it on a much larger stage.

Help is on the way

Bill Brown entered his first season as coach at Colonial Forge High School in 2007 with an array of experience – he’s inducted into the Virginia High School Hall of Fame – and a vague understanding that help was on the way.

“We had been told that (Blake) was a good junior high player, that he and his brother were talented kids,” Brown said. “We did not anticipate them being varsity players.”

The Frohnapfel brothers and fellow freshman receiver Tim Scott, who now plays at North Carolina, all arrived together and quickly found playing time. Blake was so impressive that he supplanted a talented senior starting quarterback after just four games.

Under Brown, Colonial Forge operated a modified version of the Wing-T offense, which is a popular style of football at that level predicated on running and using misdirection. Rarely does an offense operating the Wing-T throw the football. But because of the talent at quarterback, Scott at receiver and Eric Frohnapfel at tight end, Brown threw the ball 12-to-14 times a game.

It was an offense conducive to winning – Colonial Forge made the playoffs during the Frohnapfel’s junior season and lost in the regional championship the following year – but it wasn’t the best for showcasing quarterback talent.

“It wasn’t really too great to be a quarterback (in the offense) but we won so I enjoyed it,” Blake said.

“(Blake) wasn’t getting to chuck the ball all over the yard like some kids get to do,” his father said.

The limited exposure only magnified his sophomore season, when Blake broke a bone in his ankle three games into the season. He missed the rest of the season and had virtually no recruiting footage from his first two years of school.

‘It was really stressful’

If it was up to Wake Forest, Blake Frohnapfel would be a scholarship player on its defensive line. It didn’t need hours of footage to project him at the next level.

“I went to a camp and (the defensive end coach) who recruited me at Wake Forest was like, ‘can you do some defensive end drills just so I can see how you do?’ “I was like ‘okay’ and I just did some drills and I guess I did well enough and he was like ‘we’re going to offer you,’ Frohnapfel said.

“I was like, ‘what?’”

Brown said Frohnapfel possessed the physical stature and athletic abilities in high school that intrigued college coaches despite never playing a down at the position. According to Brown, “Blake could do everything his brother could do.” All coaches had to do was look at the Colonial Forge defense to see the twin Frohnapfel, Eric, excelling at defensive end.

It was an idea even Blake’s father fancied as West Virginia and Vanderbilt also wanted to convert his son to defensive end.

“I was sort of pushing Blake toward Wake Forest,” he added later. “(Blake) said ‘nope, I’m going to play quarterback and Marshall wants me to play quarterback and that’s where I’m going.’”

Brown always believed Blake was capable of playing quarterback in college.

“I really did because of two things,” Brown said. “One, he was talented. And two, his work ethic was so good. He and his brother were committed. His brother played lacrosse, so in the spring he and his brother came in and met with me at 6 a.m. and lifted weights because his brother couldn’t get it after school.”

Marshall was the only FBS program to show heavy interest in Blake as a quarterback, while the rest of his offers came from FCS programs. Marshall was one of three teams (James Madison, West Virginia) to offer both Blake and Eric. Blake adored the interest Marshall showed him and was sold early.

But his brother originally committed to West Virginia, posing a significant problem. Neither had ever played organized football without the other. Combine that with the fluid process that is college football recruiting and the stretch leading up to both brothers making a decision was a stressful time.

“I thought when I was earlier in high school that I would enjoy (recruiting) a lot and it would be a lot of fun, but it was really stressful,” Blake said.

“It was really stressful because a lot of coaches were like ‘Well, here’s an offer and you have until tomorrow night to decide.’ Some teams would do that…my brother faced the same situation when a team was like, ‘If you don’t take the scholarship in two days, it’s gone.’ So we’re sitting there with our family kind of stressed out trying to figure out what school.”

Late in the process, Eric reversed commitments and joined Blake in pledging allegiance to Marshall, much to the delight of Blake, who was dead-set on wearing green and white.

Taking a gamble

Blake knew he wasn’t the only quarterback who committed to Marshall entering 2011, but he didn’t know much about the other guy.

“I knew there was another guy that was in my class,” Frohnapfel said. “And when I got there, I kind of realized this kid’s the real deal.

That kid was Rakeem Cato, a 6-foot-1 quarterback who wasted little time finding the field at Marshall, starting 10 games as a freshman. In 2012, he was named Conference USA MVP. He followed that up by winning C-USA Offensive Player of the Year in 2013.

In other words, Frohnapfel was stuck.

“It was frustrating because I knew I could play,” he said. “I felt like I did all the things I had to do off the field and I was working out hard and doing all that stuff and I still wasn’t getting a chance. Rakeem Cato is just really a once in a generation player at Marshall. I got sick of going to games and not playing.”

Despite the lack of playing time, those around the program held Frohnapfel in high regard.

In a game against Western Carolina, Frohnapfel said he “ran over” a Catamount defender, which caught the attention of a group of middle school fans who attended every game. Quickly, the “Frohnies Crohnies” were born.

“They just loved it,” Frohnapfel said. “They would just sit in the stands and yell at coach (Doc) Holliday and tell him to put me in. They had signs that said ‘Frohnapfel for Heisman’ and, plus, I was a holder there so they made signs like ‘Frohnapfel’s the best holder in America.’

The group of kids humored Frohnapfel, who kept a collection of their signs in his apartment. He said the running joke on the team was to wonder what type of material the “Crohnies” would deliver.

Marshall offensive coordinator Bill Legg also lauded Frohnapfel, although the forceful suggestion from the teenagers didn’t persuade Legg to find more playing time for Frohnapfel.

“Even though he was a backup quarterback, he was still one of the leaders on our football team,” Legg said.

“How often does that happen? Your starting quarterback you expect that from, but your backup quarterback? I mean that shows how much respect our coaching staff and our football team had for that kid. Even though he wasn’t a starter, he was an integral part of our football team.”

Frohnapfel grew frustrated watching games from the sidelines. Outside of his performance against ECU, Frohnapfel was relegated to strictly mop-up duty. As his sophomore season progressed, he knew a change was necessary, he knew he had to take a gamble.

“It was over the course of the season,” Frohnapfel said of his decision to transfer from Marshall. “I’d be sitting on the sideline kind of mad during games thinking, ‘Man, I wish I could play. I’m doing all this work and I don’t get to play in this game.’”

“Oh, it’s heartbreaking,” said his father, who spent hours on the couch discussing a variety of options with Blake.

“You see kids who have a lot of talent and, for whatever reason, the football gods don’t smile upon them and events can transpire and nothing happens. And I thought he could end up being one of those kids.”

Dinner for three

Within two weeks of hearing Frohnapfel was available, UMass coach Mark Whipple and quarterbacks coach Liam Coen jetted to Huntington, West Virginia, to meet with him face-to-face.

Whipple was tipped off by Legg that he had a quarterback looking to transfer that might fit Whipple’s pro-style system. He and Coen met with Frohnapfel over dinner to discuss their options.

As Frohnapfel arrived at the restaurant, he already faced an issue. Who was Mark Whipple, anyway?

“At the time I didn’t really know,” he said. “I knew about Coach Whipple and what he did but I wasn’t even sure what he looked like. So I walked into the restaurant and I walked up to the hostess and I was like, ‘Have you seen an older gentleman walking in with a UMass shirt?’ And she was like, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about.’

“So I was like, ‘I’m just going to stay in here and hope a guy with a UMass shirt walks by,’ Frohnapfel said with a laugh.

Whipple did eventually walk by and the three met for about an hour. Frohnapfel entered with a cursory knowledge of Whipple’s past endeavors – he’s coached in both the NFL and college ranks – but never felt like he fit the traditional style of offense Whipple employed.

Nonetheless, he was receptive to the message Whipple preached

“It wasn’t like he was saying, ‘You’re going to be a starter,’ Frohnapfel said. “It was, ‘You’ll have a chance to come here and play and do these things.’ And that’s what I really liked because I wasn’t asking for him to say I’d be the starter, I didn’t want that.”

Blake’s father said the dinner was the primary factor in helping Blake make up his mind. Within a week, Blake was in Amherst on an official visit. He desperately wanted the trip to work out, for UMass to be the one.

Of course, other factors were in play.

Taking his own path

Frohnapfel’s leaning comfortably to his left, one arm propped up on the arm of a couch. He sits in a cluttered media relations office, a coffee table-turned-storage desk at his feet. He’s envisioning life after football, perhaps even life in his own office, perhaps even overlooking his own football facility.

Perhaps even running a professional football team.

“I always say my dream job is to be the (general manager) of an NFL team,” Frohnapfel said. “All these years I’ve learned so much about football. … I’d like to use it in a way. If I can add the whole business side as well, I feel like having that combination will set me up to possibly work my way up to one of those jobs.”

Frohnapfel frantically spent the weeks following his redshirt sophomore season scouring the Internet for top business programs with an MBA. If the program was suitable, he’d check to see if the school even had a football team. If that team didn’t already have two quarterbacks vying for playing time, he’d add them to the list.

UMass sat perched atop the list, followed by Eastern Kentucky and William & Mary. The UMass sport management program’s reputation combined with turnover in the football program made it the ideal landing spot for Frohnapfel.

Whipple agreed, offering Frohnapfel a scholarship and a chance to compete. Frohnapfel loaded up with 19 credits worth of business classes in his first semester on campus. He’ll take all business classes this year and all sport management classes next year while pursuing a dual master’s degree.

Considering the combination of his course load and his football schedule, the department didn’t initially advise that path.

“When he initially spoke to the program they said, ‘You have to pick,’” Steve Frohnapfel said. “(They said) you can get the MBA or get the sports management graduate degree but don’t try to do both, that will be overwhelming to you.

Eventually, the department relented and told Blake he could try it. Armed with a scholarship offer, a chance to pursue his academic dreams and the allure of consistent playing time, Frohnapfel arrived on campus in May.

Without any immediate family, barely any students on campus and a brief understanding of who was and wasn’t on the football team, Frohnapfel moved away from his comfort zone for the first time.

‘Obviously, it’s very exciting’

Turning Amherst into his own personal comfort zone is a day-by-day process, one that initially began in May to lukewarm results.

“I came in here in May and I was one of the only guys here,” Frohnapfel said.

“And I’d see people walking around and I’m like, ‘I don’t know if he’s a football player or not.’ It’s like you have to walk up to them and ask, ‘Hey, are you a football player?’ So it was a weird situation because I’m in my dorm room like, ‘What am I doing?’”

But he slowly eased into life in the Pioneer Valley.

It started with a permanent housing situation. As Frohnapfel fretted over where to live, he received a text from teammate Matt Sparks asking if he needed a place to live. Now, he’s settling into life as the roommate of three offensive linemen in Sparks, Josh Bruns and Fabian Hoeller.

Even the football field brought along change.

Frohnapfel learned a brand new pro-style offense under Whipple. Even taking standard drops from under center were new for Frohnapfel, who took snaps in the shotgun at Marshall. He says he’s getting better each day but needs to play better – he went 9-for-22 for 147 yards, a touchdown and an interception in the season-opening 30-7 loss to Boston College – as the season progresses.

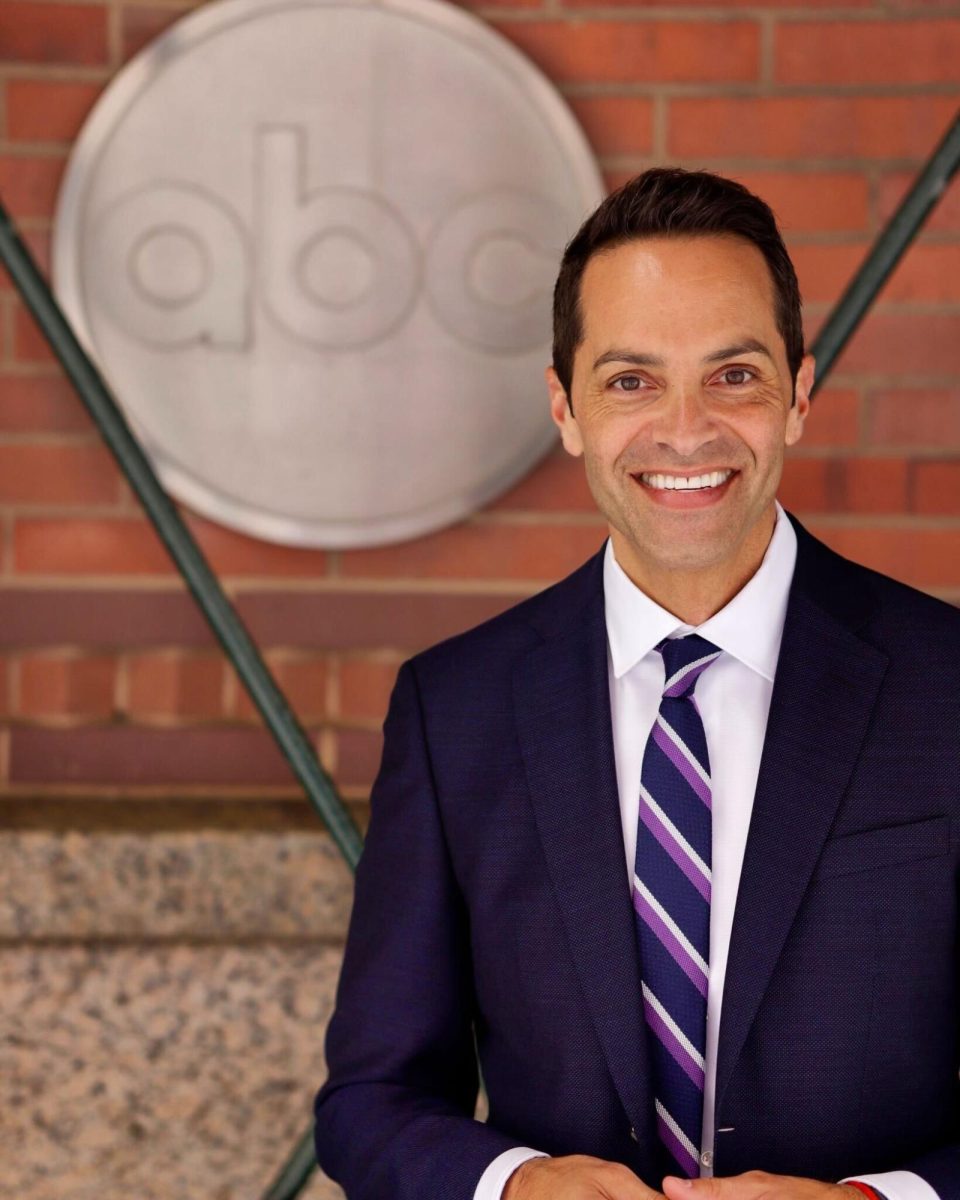

But the addition of Frohnapfel – the ushering in of a new era and an air of change – brings hope back to McGuirk Stadium. There’s a leader at the top now and if Frohnapfel can continue to inspire optimism and deliver results on the field, he’s destined to be the face of UMass football.

“With Coach Whipple coming back and coming in with a change of culture, I just happen to be the new guy,” Frohnapfel said. “I’ll be the one that was the quarterback at that time when we helped get UMass back to where it was. Obviously, it’s very exciting.”

Perhaps one day, if he does bring UMass back to where it was, he’ll have a better celebration planned too.

Mark Chiarelli can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @Mark_Chiarelli.