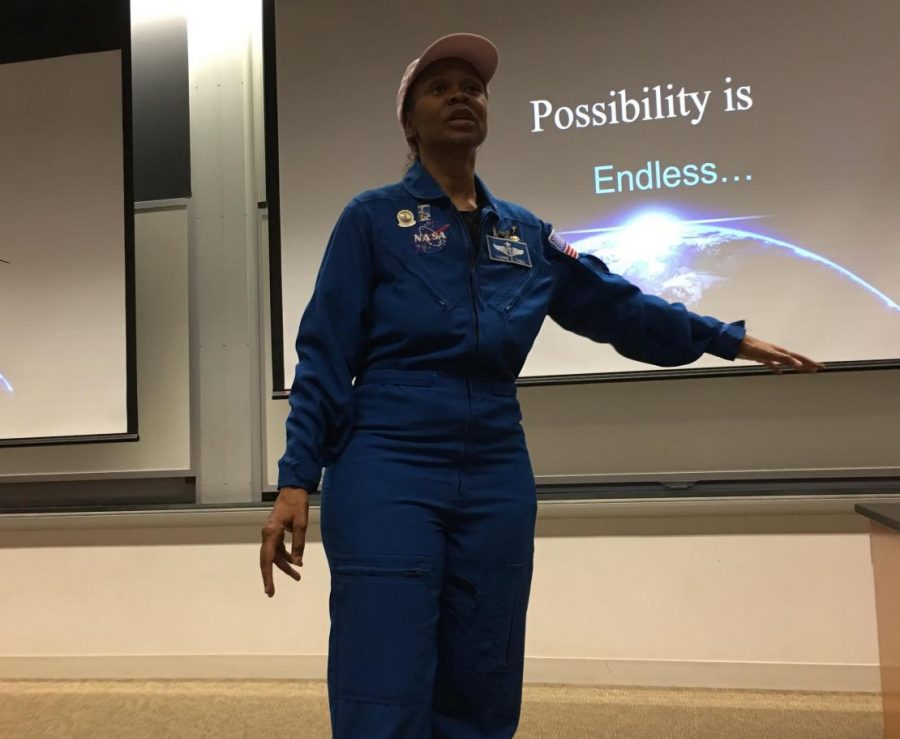

NASA astronaut Dr. Yvonne Cagle spoke in Smith College’s Ford Hall about NASA’s ambitions in the upcoming years and human readiness to cope in the harsh environment of outer space.

The lecture began with Smith College professor of engineering Susan Voss introducing Dr. Cagle and her accomplishments.

Voss said, “Dr. Cagle got a B.S. degree in biochemistry in 1981 at San Francisco State University and then she went on to medical school at the University of Washington in 1985. Over the next several years she earned a certificate in aerospace medicine, she did a residency in family medicine and she became an air force flight surgeon. In 1996 she was part of NASA’s astronaut class…what we learned today is 15 years after she graduated as an undergrad she just came back to her passion about space.”

Dr. Cagle talked about her childhood experiences watching the Apollo 11 moon landing that catalyzed her lifelong passion.

Cagle described her father “silently pointing to this grainy image on our TV…of humans walking on the moon for the very first time. Oh my God, you haven’t lived until you’ve experienced that moment.”

However, unlike 50 years ago, Cagle said, “Now space is no longer just a destination, it’s actually about the journey. It’s now a demonstration platform for all sorts of innovation.”

“Folks, we are not going just to [the] International Space Station. We are going to Mars; 2035 we plan to go to Mars,” Cagle said. She added, “We plan to go to Mars … by being prepared. Mars is six months [of travel away] at best, nine months on average [and] two years if we get the math wrong.”

Dr. Cagle explained that to be well prepared for the new horizon of manned interplanetary exploration, NASA will retrace its steps to the closest replica of the red planet humanity has access to, our own moon.

“So we’re going back to the moon. 2024, six years from now. Two cislunar missions, the first one in 2024 and that’s when we’re going to be on the moon for 30 days, a lunar mission testing the vehicles, communication, satellites, CubeSats [miniature satellites], robotics, all of these sorts of things to demonstrate that we kind of have a handle on things,” she said.

On these test missions, such as the 2024 lunar launch, humanoid robots will be the precursors before any actual human sets foot on the ground. The robots will be outfitted with biological components akin to those of a human being including cochlear hearing implants, retinal eye chips, 26-degree hand rotation and a circulatory system pumping synthetic blood.

Cagle’s primary focus of the lecture was the physiological changes occurring within the human body as it naturally optimizes itself to the lower-gravity conditions of space.

These bodily changes, according to Cagle, include the narrowing of the torso, separation of vertebrae in the spine causing height increases, arms and legs thinning out, toes and fingers elongating, changes to the human genome by radiation exposure and, as Cagle explained, “our blood volume starts to float upwards towards our chest, it normalizes there, but then because the skull stops it from going any further, hydrostatic pressure builds up.”

Through her own research into the subject and her personal mantra of “follow the fluid trail,” Cagle explained, “Wherever we lose hydrostatic pressure seems to be where the muscles and the bones lose the most of their content [and] their mass. Conversely, wherever hydrostatic pressure builds up is where you have new bone being laid down.”

“The important thing to know, though, is that when you go to Mars, if you’ve been there right around 84 days, your growth hormone drops off and that means that you really start to decondition and weaken,” she said. “Six days after it drops off, you can lose somewhere around ten percent of your muscle mass.”

Cagle highlighted this muscular depletion as a potential liability to movement and feeding oneself even in the best of circumstances.

She also said, “If you lose muscle mass that fast and you’re not injured, how fast do you lose it if you’re injured? Maybe it’s the same rate. The important thing is if you’re already weakened and you get injured, it’s going to be really hard to rehabilitate.”

The lecture then honed in on the subject of “kinesio-engineering,” which Cagle described as “dynamic loads on the muscle in order to accelerate the healing and restore resiliency of a limb after its been injured, whether it’s been days or decades and, in most cases, within a week’s time.”

Cagle said, “Somehow we have to find a way to build resistance when there’s no gravity. We have to find a way to have a gym when there’s nothing but your own body. So your body becomes the gym and then we have to figure out how we can generate resistive loads to manage those dynamic loads; that’s called ‘lift.’”

She showed off a portable device similar to a harness meant to induce lift, a concept which Cagle compared to a car caught without traction where the energy potential to get out of the situation is present, but it’s only a matter of administering the proper alignment and technique to ameliorate the issue and return to normalcy as if nothing happened.

“There’s usually an immediate, significant and noticeable reduction of soreness, swelling and stiffness,” and “if you’re not injured [lift has] been demonstrated to show [growth] of new powered muscle in record time with very little effort,” Cagle said.

Nevertheless, Cagle stressed that lift requires vigilance by trained individuals in order to be performed properly and to yield the intended results.

Micha Heilman, a junior astronomy major and physics minor at Mount Holyoke College, said, “The fact that we have a female engineer astronaut was definitely a big draw to the talk.”

“I feel like she had a great atmosphere, keeping it light and keeping us engaged and also having a lot of anecdotes that stem from all of her life,” Heilman said.

Heilman, who works with the Medical Emergency Response Team at Mount Holyoke, was particularly enthused about Dr. Cagle’s physiological foresight.

“Wouldn’t that be the most interesting thing to try and wrap your head around when you’re on Mars, when there’s a third of gravity, ‘How do you do effective chest compressions?’ ‘How do you get blood flow?’ It’s just the intersection of being in space and all the medical anomalies that could happen totally opening up a new realm of things to think about. I’m not going into medicine, but I can appreciate it nonetheless,” she said.

Chris McLaughlin can be reached at [email protected]and followed on Twitter at ChristMcLJournal.