The famous book reviewer Orville Prescott begins his review of “Doctor Faustus: The Life of the German Composer Adrian Leverkühn, Told by a Friend,” with the following sentence: “Strange indeed are the works of Thomas Mann and strange the mind that gives them birth.”

Having read the book this past summer, I can say with complete and vigorously affirming confidence I have no reason, none whatsoever, to disagree.

This is not the play by Christopher Marlowe or by Goethe, though it bares its name. Mann’s “Doctor Faustus” follows the life of Adrian Leverkühn, a fictitious German composer who intentionally contracts syphilis, hoping that the resulting brain decay will drive him to madness, and thereby enable him achieve creative genius–a modern take on the Faustian bargain.

This questionable life choice goes just as intended. Leverkühn goes on to achieve legendary status, introducing artistic innovations similar to those of real (and nonsyphilitic) composer Arnold Schönberg, before suffering mental collapse and dying 10 years later. At the same time, Germany goes down a similar path of self-destruction- the rise and downfall of Nazi Germany during the first 50 years of the 20th century, a series of events that Leverkuhn often compares to the apocalypse.

“Faustus” is a kind of biography, relayed through, as the full title states, the composer’s friend, the curious and at times exuberant philologist Serenus Zeitblom, who is writing the history of his friend’s life 15 years after his death, as the World War II comes to a close, all so that his hero will not be forgotten.

“I am writing for posterity…when details of so thrilling an existence, however well or ill-presented, will be more eager and less fastidious,” Zeitblom writes.

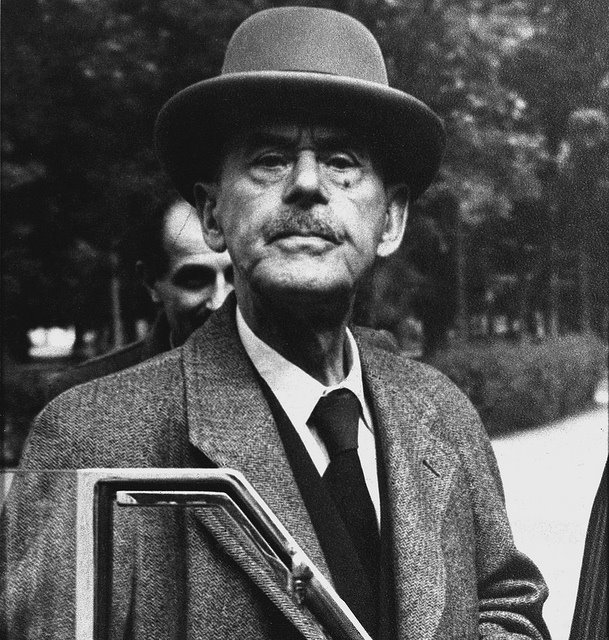

The work was originally written in German, and its author, Thomas Mann, is one of the biggest figures of German literature in the last century. “Faustus” is one of his final novels, published in 1947, when Mann was 73. He wrote it, interestingly enough, while living in Malibu, California, during his self-imposed exile from Germany during the years of the Nazi government.

Analysis

On the surface, the work seems to retrace its author’s most prolific themes. For another lamentation of the dangerous path of European culture prior to 1945, see “The Magic Mountain.” For a deeper exploration of the relationship between the creative mind and madness, see “Death in Venice.”

But what is so magnificent and arresting here is that Mann manages to express these themes all at once, setting them against each other. The result is a rich tapestry of meaning that one would be hard-pressed to find, even in Mann’s other works. In fact, when it was first released, the New York Times went so far as to call it a “symbolical allegory for our own time.”

This is the moment in the review when you probably expect me to offer some trivial point about how this book, with all its talk about a declining culture and its troubling political backdrop, is chalk-full of “lessons for our own time.” And, in a way, yes. And, in a way, no. For those of you who want to see that in this novel, I do not need to elaborate to make the parallels clear. But for those of you whose interest is less political and more aesthetic, I encourage you to read it nonetheless, because there is far more here than simply a slogan. It is a story about an artist, after all, and offers plenty of lessons for those who would be interested in such a life. I would go into them here, but it is best these lessons are left to the reader (and alas, my article runs too long). Rest assured: they are profound.

Evaluation

That being said, readers may find a barrier in the wordiness of the text. Take, for example, the following sentence: “In the works of the last period they stood with heavy hearts before a process of dissolution or alienation, of a mounting into an air no longer familiar or safe to meddle with; even before a plus ultra, wherein they had been able to see nothing else than (…) an extravagance of minutæ and scientific musicality–applied to such simple material as…” It goes on.

Some of this I blame the age of my particular translation. It is the 1971 edition from Vintage books; there has since been published a far more fluid version. But other instances are no doubt the exuberances of Mann’s style. His sentences are as long and syntactically complex in German as in English or Japanese, for that matter, and even in small print they routinely run to four lines (as seen above).

The same can be said of the novel’s structure. It can feel, at times, exhaustive. One long chapter is devoted to the main character’s college education–specifically to transcriptions of the lectures he attended–all because of, to quote the narrator, “the imperative desire to ‘keep track’ of [Leverkuhn]” (111). Other moments, the narrative seems to fade away, and one seems to be reading an essay, with Mann speaking directly to the reader; as one can imagine, this is sometimes off-putting.

But, oddly, what won me over is the voice, that same Zeitblom, who speeds along as if performing rather than writing, unable to go back and revise. Take, for example, the opening for the fifth chapter: “the chapter just finished is…for my taste, much too extended. It would seem only too advisable to inquire how the reader’s patience is holding out.” And again, a few paragraphs later: “I am entirely aware that with the above paragraph I have again regrettably overweight this chapter, which I had quite intended to keep short” (31). Isn’t that wonderful?

Trent Babington can be reached at [email protected].